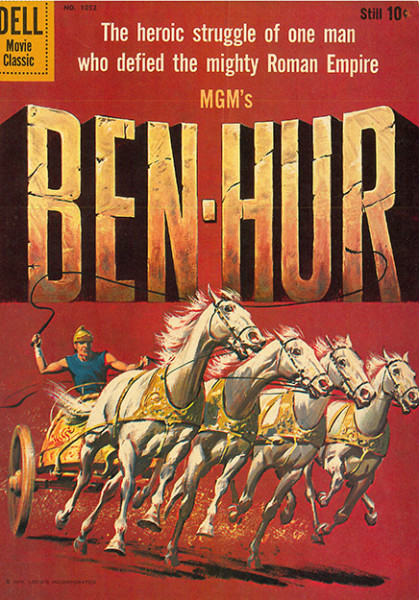

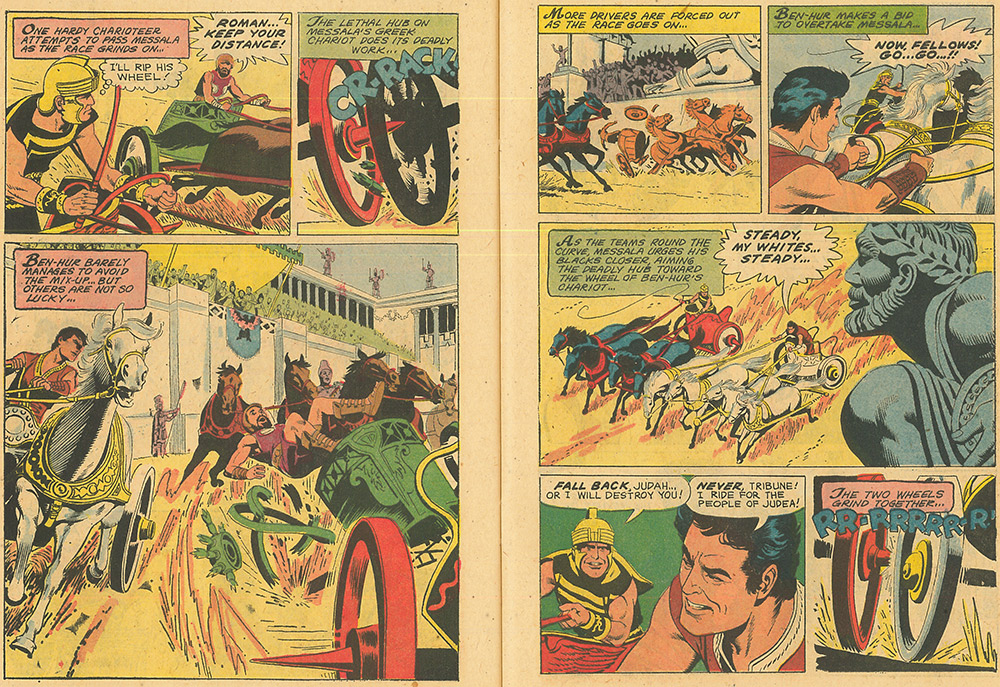

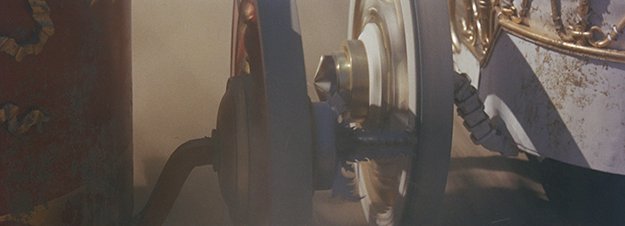

The Ben-Hur adaptation, drawn by Russ Manning, best known for a series of Tarzan books and newspaper strips in the mid-’60s, was an extreme distillation of the film’s three-and-a-half-hour run time. The comic creators obviously recognized the importance of the chariot race, devoting a disproportionate number of pages to the scene (five of 32 pages) given the length of the film. There is also a bit of formal deviation within the scene, with one page containing two small panels and a larger, arresting third panel taking up most of the page. There are also points of similarity between individual panels and shots in the film including the close-ups of wheels smashing into each other and Messala being crushed to death after his chariot is destroyed.

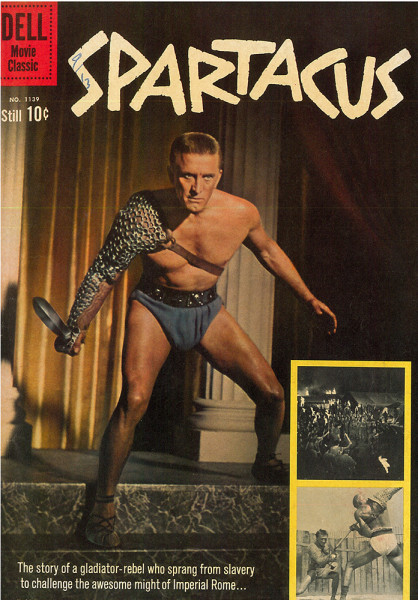

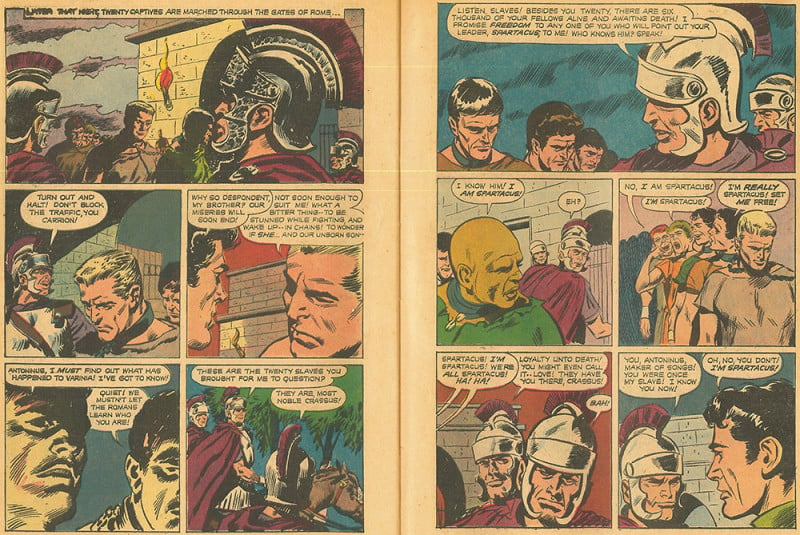

The adaptation of Spartacus benefits from the artwork of John Buscema, a giant in the field and known for a long run on Conan the Barbarian for Marvel. The story sticks fairly faithfully to the film with nearly all scenes not including Spartacus omitted. The famous “I’m Spartacus” scene is depicted, but later and outside the walls of Rome where Spartacus eventually kills Antoninus. And while we see Varinia ride off at the end of the story as she does in the film, we only see Spartacus being led to meet his fate and not his gruesome crucifixion.

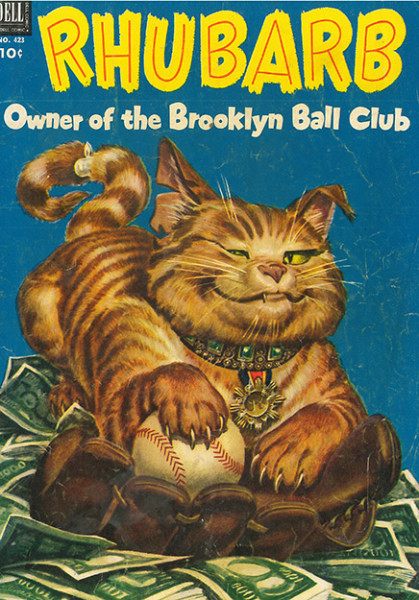

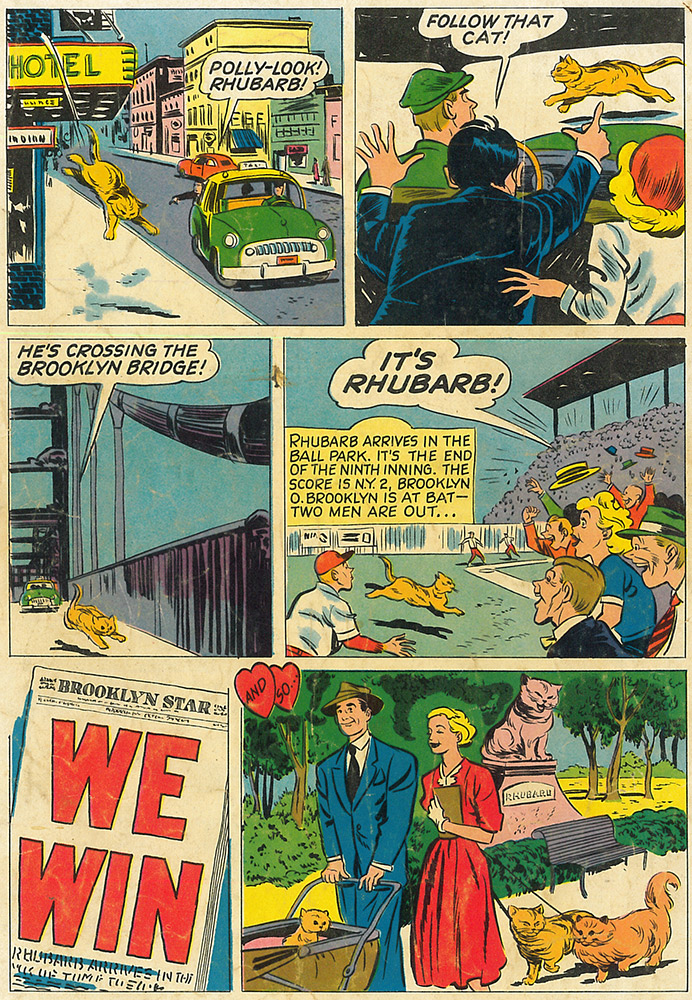

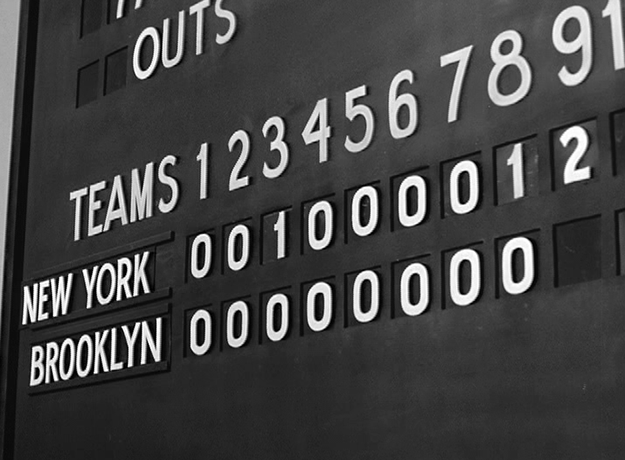

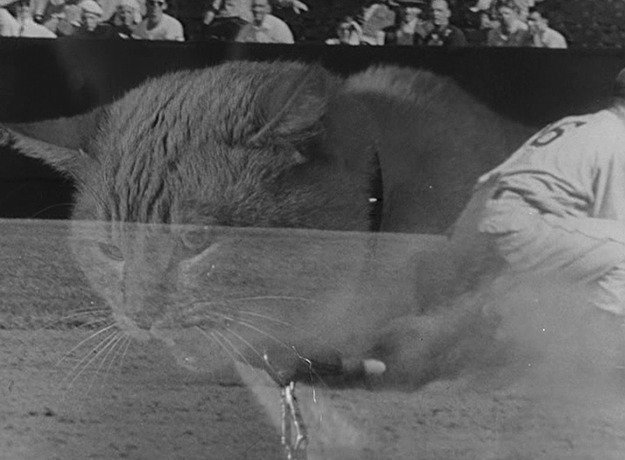

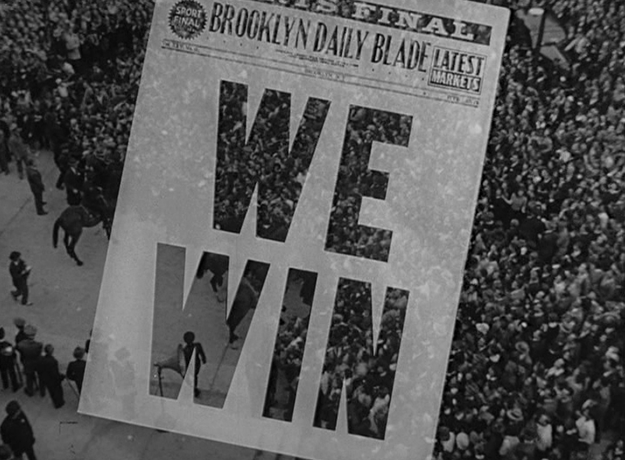

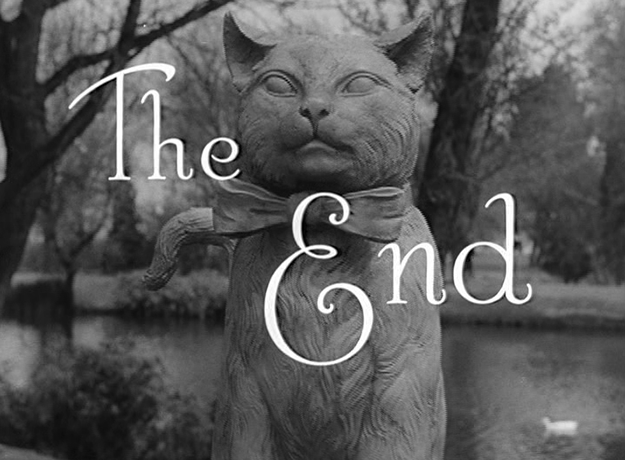

Shorter films, especially comedies, lend themselves more readily to adaptation from screen to page. Rhubarb (51), about a cat who inherits a Brooklyn baseball team, features the work of Don Gunn, whose visual style is an ideal complement to the fanciful premise and comic tone of the story. The comic is a faithful adaptation until the end when it appears the writers discovered they had little space to work with and had to collapse the film’s climax into a single page. Unlike most of the other live-action adaptations, Rhubarb continued for a few more issues.

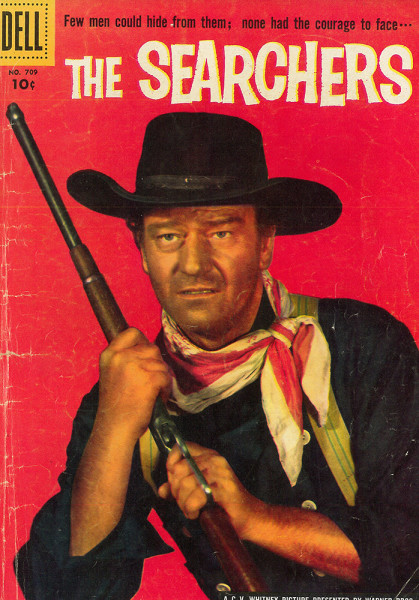

Perhaps the most striking example of how different artists might approach the same material can be seen in the different treatments given to the end of The Searchers. The framing of John Wayne looking out through the doorway of the Jorgensen’s home is perhaps the most memorable in Ford’s entire body of work. In the comic, drawn by Mike Roy, the climax of the film—from Debbie’s “rescue” to her return to the Jorgensen’s—is rendered in only five not-terribly-memorable panels, and the story is wrapped up with striking economy.