Tomu Uchida: Genre Artist

Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka

The fact that many important Japanese filmmakers have been overlooked or ignored by foreign critics and distribution companies should come as no surprise. The Japanese film industry has been a robust and prolific one since before World War II, and its five major studios (six until 1960) operated very much along the lines of the classical Hollywood studio model, elevating filmmakers based on their prior box office performance and critical regard, and assigning top projects to them accordingly. Even without including independent filmmakers or those who broke away to form their own production companies, like Nagisa Oshima or Kaneto Shindo, the list of notable Japanese studio directors deserving of critical attention is impossibly long.

Perhaps the most significant of these overlooked commercial artists is Tomu Uchida, who died in 1970 but whose works—apart from a five-film series of historical swordplay epics—remain completely ignored on home video in America, with no official distribution whatsoever. Although Uchida made 70 films, all but four of his pre-war productions are lost or exist only in fragments, and yet his postwar output—over two dozen titles—is of a uniformly high quality, and comprises both period swordplay epics and modern melodramas or social realist stories. Part of the blame for his lack of exposure outside Japan lies with the studio where he made most of his postwar films, Toei, which itself was formed after the war ended but which showed very little interest in exporting its films of the 1950’s and 60’s to foreign territories, or in submitting them to prestigious overseas film festivals, which is how the works of Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi were first introduced to the West. Toei’s films were among the most commercially successful in Japan during those decades, with their period swordplay films ruling the box office of the 50’s and honorable yakuza films doing the same in the 60’s. Genre movies weren’t typically considered high priorities for foreign export, and since Toei was making plenty of money on them at home, foreign sales were a seldom-considered afterthought. Consequently, the films of Toei house directors like Uchida, Tai Kato, Kosaku Yamashita, Masahiro Makino, and even later filmmakers like Kinji Fukasaku and Sadao Nakajima, were never submitted to foreign festivals, rendering them effectively absent from the history of Japanese filmmaking as written by non-Japanese critics and scholars.

This regrettable inheritance has been slowly corrected as more and more writers, piggybacking off the efforts of film programmers in Japan and elsewhere, are “discovering” these overlooked auteurs and bringing them to the attention of audiences and distributors around the world. In the case of Uchida, a recent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—sadly not complete, or as complete as would be possible considering his lost films—expanded on a prior retrospective at BAM in 2008 (which showcased ten of the director’s works) and screened uniformly gorgeous 35mm prints of nineteen of Uchida’s works, ranging from his sole surviving silent film (1933’s Police Officer) to his 1968 classical yakuza melodrama Hishakaku and Hiratsune: A Tale of Two Yakuza, the last film he was able to complete before his death.

A Hole of My Own Making

Of the titles not screened in 2008 at the BAM series—an offshoot of parallel retrospectives held in other cities, including Rotterdam and Tokyo—the most significant to be made available is Uchida’s 1939 neorealist epic Earth, considered by many critics his magnum opus and certainly most significant prewar statement, which was screened in a 2006 restoration combining elements discovered in Germany and Russia, but still missing the final 20 minutes. (That part of the story is conveyed via onscreen text.) Made for Nikkatsu’s Tamagawa Studios and coscripted by frequent prewar collaborator Yasutaro Yagi (who also wrote Uchida’s caustic 1955 family melodrama A Hole of My Own Making), Earth (the Japanese title could also be translated as The Soil) is the bleak and bitter look at a family of farmers in northern Japan who begin the film already in a desperate situation: the hard-working mother has recently passed away, and the stubborn father is at odds with his father-in-law, whose past debts make it impossible for them to make any headway toward improving their lot in life. The father is indebted to a benevolent but feudal landlord and suffers the scorn of the other villagers; his battles with his family, the elements, and himself are reminiscent of German or Soviet filmmaking styles, yet Uchida’s outlook is completely sympathetic with the plight of the unlikeable protagonist. Even when the family’s shack burns down late in the film due to an easily avoidable accident, blame is withheld, other than that which the characters assign to themselves.

Midway through his career, Uchida spent nearly 10 years working in China as part of the Manchuria Film Association, at first helping to turn out propaganda efforts for the war, and then staying on after Japan’s defeat to assist with the development of the Chinese film industry. In 1953 he returned to Japan, only recently liberated from Allied occupation, and joined the new Toei studio, for which his first film was 1955’s A Bloody Spear on Mt. Fuji, starring prolific period actor Chiezo Kataoka, whose career dated back to Japan’s silent era. If Uchida’s wartime experiences are felt in the film at all, they are reflected in his character’s ambivalent attitude toward feudal authority and the director’s elevation of the lowliest characters—Kataoka in this case plays a mere spear-carrier for a drunken, simple-minded samurai lord—over their societal superiors. But the film distinctly lacks the kind of nihilism or anger which would be reflected in the next decade’s antiauthoritarian samurai or war films by the likes of Masaki Kobayashi or Kihachi Okamoto; instead, Uchida’s approach is one of gentle humor and good-natured humanism, channeling Sadao Yamanaka’s prewar film Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937) in its depiction of the sake-loving samurai as “just folks” in his relationship with not only his servants but more or less everyone he meets.

This is not to say that Uchida’s critique of inherited position and authoritarian systems doesn’t have teeth: he manages both to lampoon the feudal order with humor (as in a scene where a stately roadside tea ceremony is interrupted by a boy defecating in a nearby field) as well as with the climactic swordplay scene, when Kataoka’s spear-carrier reacts to random injustice and senseless violence by lashing out, seemingly not only against the stock samurai villains who have killed his master due to a perceived slight, but also against the entire feudal system. Beyond its narrative value, the magnificent fight scene also shows off Uchida’s technical skills, something evident in most of his postwar films. In Bloody Spear, Kataoka takes on a group of villains in an open space surrounded by sake barrels, which are successively broken open or punctured as the fight rages all over, completely changing the landscape on which the action is taking place. Uchida also often shoots this scene—as with the dynamic set pieces in most of his other films—from above and with a moving camera, altering not only the audience’s moral point of view but also distinguishing his work from that of someone like Kurosawa, who preferred a down-in-the-dirt aesthetic for his action scenes. This dynamism and god’s-view perspective also wasn’t limited merely to Uchida’s samurai films; his follow-up to Bloody Spear, the brilliant social-realist-drama-cum-quasi-musical Twilight Saloon (1955), involves a host of characters interacting over the course of one night on a single, massive, indoor set, and Uchida’s camera ranges over the action in very much the same way.

Outsiders

Kataoka would go on to star in another half-dozen of Uchida’s films, including a trilogy of swordplay dramas based on a serialized novel about an evil samurai and the karmic justice inflicted on him, in which he was cast as the unlikely lead. The first parts of the novel, written by Kaizan Nakazato as Daibosatsu toge (The Great Bodhisattva Pass), were eventually turned into Kihachi Okamoto’s 1966 film The Sword of Doom, starring Tatsuya Nakadai. But the first film version was made in the mid-1930s by Hiroshi Inagaki for Nikkatsu, followed by a trilogy made at Toei in the early 1950s by director Kunio Watanabe, starring Kataoka as Ryunosuke Tsukue. Kataoka reprised the role in 1957 for Uchida’s first installment, but by this time he was considered a bit too old and portly to believably portray someone referred to as the “young master” of his sword-instructor household. Nevertheless, over the five and a half hours of the remarkably engrossing trilogy, made between 1957 and 1959 and given the slightly inappropriate English title Swords in the Moonlight, Kataoka more than grows into the role, particularly in capturing the enigmatic soul of his antihero protagonist and allowing audiences to sympathize with a murderous character whose primary sin may be one that was determined for him before he was born, if you accept the Buddhist philosophy informing the story. The very rarely seen three-part series, not included in BAM’s 2008 retrospective, was one of the most important inclusions to MOMA’s program.

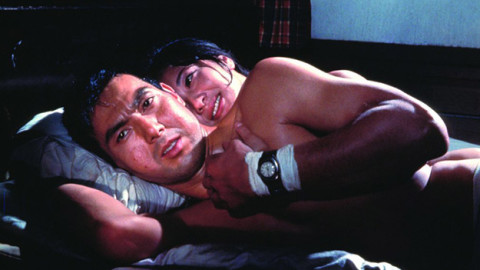

While most of the Daibosatsu trilogy is realistic in its depiction of Ryunosuke’s travels and misadventures, as it draws to its conclusion and karma catches up with the protagonist, Uchida begins to incorporate some highly theatrical elements into the film’s style, transporting viewers into a surreal realm of Buddhist heavens and hells, partially to depict the tormented inner lives of its characters. This wasn’t a career anomaly, as Uchida continued to conduct such formal experiments in his later films, most notably the 1962 kabuki adaptation The Mad Fox, the story of a young samurai who loses his mind after a tragedy and flees into the forest, only to marry and father a child with a shape-shifting fox-spirit, a film that abandons realism altogether in its phantasmagoric second half. His Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959) also self-consciously breaks with filmic realism by gradually introducing not only its eponymous author directly into the story, but also using bunraku puppets to depict its climax. But defying expectations, Uchida’s masterful period tragedy A Killing in Yoshiwara (1960), also a kabuki adaptation, is played completely naturally almost until the end, betraying its source, only to shock the viewer at the violent climax with a surreal presentation of the bloodshed they’ve been expecting all along, which is, like the climax of Bloody Spear, shot from overhead and afar, though this time through a veil of falling cherry blossoms.

Very much a genre stylist in the mold of golden-age Hollywood directors like Anthony Mann or Raoul Walsh, Uchida showed little discernible personal style to mark him as an auteur in the French critical mold, but the uniformly high quality of his works and his ability to succeed in a variety of genres mark him as a filmmaker very ripe for (re)consideration by critics. His work also refuses to be pigeonholed; for example, defying his reputation as a period film director, 1957’s The Eleventh Hour is an ensemble-cast, social realist melodrama about a rescue at a caved-in mine that equals anything made by Hollywood during the same era. At the same time, Uchida is responsible for some of the most remarkable swordplay films of the 1950s and ’60s; his five-film Musashi Miyamoto epic (not screened at MOMA), starring Kinnosuke Nakamura in the title role and Ken Takakura as his arch-nemesis Kojiro, surpasses the better-known Inagaki Samurai Trilogy starring Toshiro Mifune in terms of both drama and swordplay, yet remains little-known in the West (despite its availability on DVD in the U.S.) After the BAM retrospective (and others) in 2008, most of Uchida’s films remained unscreened and undistributed in America, so with MOMA’s bigger series recently ending, it’s time again to encourage distributors like the Criterion Collection, Kino Lorber, and Arrow Video to bring out more of the director’s masterpieces, both for critical reconsideration and for those whom the veteran filmmaker will be a major new discovery.

Tomu Uchida: A Retrospective runs October 21–November 7 at MOMA.

Marc Walkow is a writer and film programmer living in New York. Formerly a director of the New York Asian Film Festival, he has also produced DVDs and Blu-rays for Criterion and Arrow Video.