The Year in Experimental Film

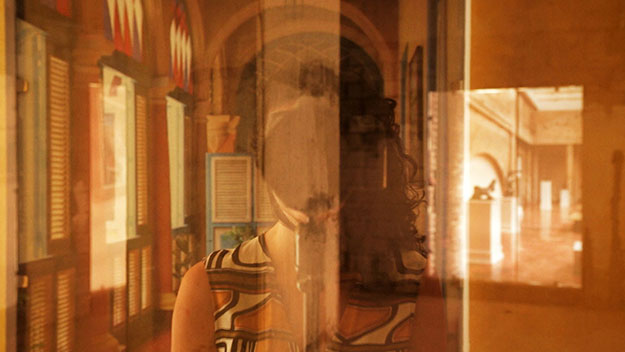

Turtles Are Always Home

Consensus had it that 2017 was an underwhelming year for cinema, a sentiment that seems to have seeped into conversations regarding the year in experimental film. Sweeping declarations tend to reflect a blinkered view of cinema, but wholesale value judgments of the year in the avant-garde feel particularly shortsighted in a field where the discourse is so strongly dictated by the vagaries of festival placement and subsequent critical appraisal. This year some noteworthy experimental features and shorts made waves through the established festival channels or at world-renowned art events, while others found favor in regional showcases, premiered online, or took a less specialized route to find receptive viewers. Indeed, in a year when arguably the most challenging piece of moving-image art was released as a limited, 18-episode television series (David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks: The Return), these past 12 months have hopefully only reinforced the fact that truly singular, uncompromising cinema is being made and disseminated in more arenas and through a greater number of exhibition networks than ever before.

With such variety comes the need for more conscientious viewing and curation. Case in point: Rawane Nassif’s Turtles Are Always Home, which slowly rose to prominence over the course of the year. Lost in the crowd upon its premiere in February at the Berlinale, the film was reclaimed by a small contingent of critics and viewers in the fall as part of Wavelengths at the Toronto International Film Festival. Part diary film, part city symphony, the short functions as both a multidimensional document of a curiously unpopulated canal district in Doha, Qatar (“a fake Venice with colorful houses,” as Nassif puts it in her artist’s statement), and a portrait of this Lebanese filmmaker’s perpetual displacement, which has found her living in seven different countries in the 10 years since she’s left Beirut. Nassif shoots the neighborhood’s pastel-hued architecture and reflective surfaces in a detached manner that highlights its intoxicatingly alien atmosphere. The film’s visual syntax follows a structural logic: the fixed perspectives together formulate a spatial coherence that’s playfully disrupted by swaying doors, angular lighting, and slight adjustments to the camera’s focus, in the process revealing new details hidden in the frame––the most striking reveal being Nassif herself, in silhouette in the final shot. Standing behind her tripod, face obscured, her voice rises on the soundtrack, singing with quiet resolve of an unmoored existence.

In its own subtle way, Turtles Are Always Home was one of the year’s most political films. Considering the current climate, it was unsurprising to see artists from across the globe responding in unique ways to urgent sociopolitical issues. Rather than the agitprop and paracinematic devices that once found currency in experimental circles, many of this year’s best shorts gave voice to underrepresented subjects in more literal terms, or endeavored to reclaim space through means generally associated with documentary. In Dislocation Blues, Ho-Chunk filmmaker Sky Hopinka took a personalized approach to the Standing Rock protests, using first-person testimonials about the camps to explore wider issues of identity and representation. Similarly, in Fluid Frontiers, Ephraim Asili resurrected the African American poets of Detroit’s Broadside Press of the 1960s and ‘70s through present-day readings of texts along the former Windsor-Detroit slave pass, while Fern Silva, with The Watchmen, confronted the prison industrial complex through a montage of Panopticon towers and found audio transmissions. And finally, in Rubber Coated Steel, Beirut-based artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan outlined and animated, with forensic attention to detail, a contested legal battle over the use of live or rubber bullets in the murder of two Palestinian teens.

El mar la mar

But the year’s three strongest political films all came in feature-length form: Ouroboros, by Basma Alsharif; El mar la mar, by the team of Joshua Bonnetta and J.P. Sniadecki; and Tonsler Park, by the ever-prolific Kevin Jerome Everson. Aside from their topical relevance, these films are further representative of a trend that’s become so widespread it’s now arguably the dominant language of experimental filmmaking––namely, a reengagement with cinema’s roots in nonfiction and an impulse toward documentary-like devices. Of these artists, Everson works closest to traditional nonfiction, and has been doing so longer than current fashions might indicate. The first of no less than five films the Ohio native premiered this year, Tonsler Park is one of Everson’s simplest and most potent works; an unassumingly powerful look at a Charlottesville polling precinct on Election Day 2016, the film captures a sense of hope and community that would prove not only fleeting but futile mere hours after the director’s 16mm camera stopped rolling. (For more on Everson see Max Nelson’s profile of the filmmaker in the November/December 2017 issue.)

Writing on Tonsler Park for Artforum, Tony Pipolo suggested the film be installed on permanent loop in museum’s nationwide. While a bit hyperbolic, such an idea isn’t entirely far-fetched; like a lot of experimental filmmakers, Everson has seen his work increasingly embraced by the art world, a once tentative relationship that’s become especially valuable for filmmakers as funding sources have dwindled in recent years. Ouroboros, Alsharif’s first feature, premiered as part of the Whitney Biennial (where recent films by Hopinka and Everson were also screened), while Bonnetta, known primarily as a sound artist, premiered a new installation alongside El mar la mar at the Berlinale. Both films adopt a poetic form to tackle contentious subjects: in Ouroboros, the Gaza Strip becomes a site of metaphysical inquiry for the Lebanese-born Alsharif, while the U.S.–Mexico border approaches pure abstraction––resembling not so much a desert pass as a purgatorial netherworld––in Bonnetta and Sniadecki’s 16mm ethnographic horror film. El mar la mar sidesteps the didactic in favor of an almost purely synesthetic approach that imagines this contested border region in visceral rather than vernacular terms. (For sheer pictorial magnitude the film was matched only by another feature I just recently caught up with: Scott Barley’s ethereal landscape film Sleep Has Her House, which the British-born artist released online in early 2017.)

Ouroboros’ cyclical narrative––based in part on the notion of the “eternal return”––traces a personal-political arc in seven movements, beginning with extreme aerial views of the Gaza Strip. Touching down for a tour through the streets of Palestine, the film soon alights upon a series of increasingly allegorical interludes in East Los Angeles, Northwest France, and Southern Italy. Through a bold interweaving of drone footage, reverse tracking shots, and dream-like episodes in which symbolic figures––whether doubles, doppelgängers, or simply ciphers––casually cross space-time coordinates and otherwise recognizable provincial spaces achieve an anachronistic majesty, Alsharif conceives of a uniquely associative manner by which to meditate on both a landscape and a lineage in danger of being erased from the socio-historic consciousness. What the film lacks in an immediately coherent thesis––arguably a byproduct of its willfully disorienting design––it more than makes up for with consistently surprising and inventive imagery. It resembles few films I can readily recall.

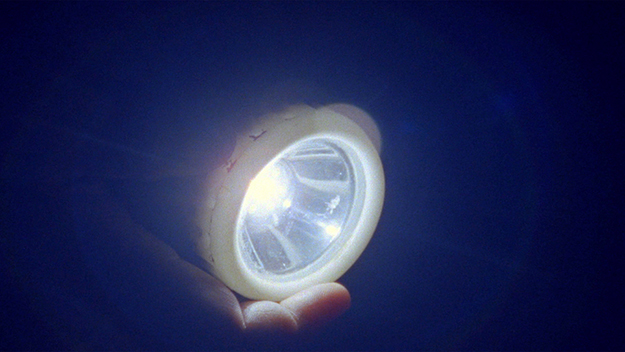

Good Luck

Overseas, in Kassel, Germany, one of the year’s other major art showcases, documenta 14, previewed (mostly as installations) a number of films that would go on to considerable acclaim on the fall festival circuit, including Ben Russell’s cross-continental mining epic Good Luck, Narimane Mari’s three-part chronicle of French-occupied Algeria Le Fort des fous, Wang Bing’s Locarno winner Mrs. Fang, an intimate study of an elderly woman slowly succumbing to Alzheimer’s disease, and two works by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel: an installation version of the duo’s first feature of 2017, somniloquies, an impressionistic account of famed sleep-talker Dion McGregor that originally premiered in Berlin, and an early excerpt of Caniba, a disturbing portrait of Japanese cannibal Issei Sagawa that later had its theatrical premiere at the Venice International Film Festival. Such art-world showcases––offering support and in some cases partial funding for these projects––help account in part for the sheer bounty of feature-length experimental films on offer this year, though the traditional festival channels, still the most effective outlet for getting these films in front of the proper audiences, turned up their own share of notable long-form works, most notably Blake Williams’s feature debut PROTOTYPE, a multivalent essay in three dimensions on the nature of image-making inspired by the 1900 Galveston hurricane, as well as the first four entries in Heinz Emigholz’s new Streetscapes series, which thus far has found the veteran German filmmaker applying his formal acumen to subjects ranging from the familiar (architecture), to the unexpected (music), to the altogether revelatory (himself).

No stranger to navigating the nuances of cinema and the gallery himself, Bosnian filmmaker Dane Komljen, following his own first feature All the Cities of the North, returned this year with a new short, Fantasy Sentences, a transfixing meditation on language, memory, and cinema’s capacity for reimagining the bounds of each. Parlaying his title’s allusion to Walter Benjamin, Komljen bookends Fantasy Sentences with slightly differing versions of a distressed audio recording in which an unidentified voice speaks ominously of a man who transforms into an animal. Proceeding from anonymous 8mm home video footage of a family vacationing in the Ukrainian countryside, to present day digital images of the same region’s overgrown architectural landscape, Fantasy Sentences is observational in tenor but suggestive of both genre cinema (or at least its European high-art equivalent, e.g. Stalker) and the more phenomenological arm of the poststructuralist school of filmmaking (and in this regard, not unlike Emigholz’s recent work). The film’s final image, an extended shot of a dilapidated cinema, sets the medium’s ephemeral traits in stark relief; accessing multiple temporal spaces in the length of a given shot, Komljen has constructed an unassumingly profound metaphor for cinema’s regenerative potential.

Nostalgia of a different kind can be found in the work of Michael Robinson and Sara Cwynar, two young artists fascinated by material culture who through very different means work to highlight the absurdity of everyday life. Robinson’s latest video work, Onward Lossless Follows, combines found audio (sourced from the rantings of what sounds like a televangelist or street preacher) and commercial imagery (lifted from advertisements, infomercials, and educational videos) into a mystifying reflection on man-made catastrophe, digitally-mediated romance, and the dangers lurking in small-town suburbia. By slowing down and overlaying footage, distending language, and pairing otherwise mundane imagery with unexpected music cues (a personal favorite: a horse being airlifted to the tune of America’s 1971 hit “A Horse with No Name”), Robinson turns remnants of some half-remembered past into an odd and unsettling trip through the American unconscious. On first pass it struck me as perhaps the filmmaker’s richest work to date; five viewings later and I’m no closer to exhausting its strangely seductive pleasures.

Rose Gold

The focus of Cwynar’s Rose Gold is narrower but no less incisive. Taking the titular color, invented by Apple for the iPhone 6, as a jumping off point to explore the semiotics of domesticity and conspicuous consumption, the Canadian-born, Brooklyn-based Cwynar applies her multi-disciplinary interests (in addition to cinema, she works in photography, print-making, and installation––each with a decidedly collagist bent) to a kaleidoscopic portrait of commercially cultivated nostalgia. In this color-coordinated trip through modern materialism, household bric-a-brac overflow in meticulously arranged tableau stagings (shot in what appears to be Cwynar’s studio or apartment) while the artist herself playfully interacts with the makeshift mockups. On the soundtrack, a man and woman engage in a volley of readings gathered from news headlines, TV spots, children’s books, and untold other sources, the object of their inquiry constantly shifting and multiplying as Cwynar’s day-glo palette similarly pricks the synapses. At once vintage and hypermodern, the film couches its critique in a visual and aural language so commonplace that its finer points are rendered that much more incriminating for their familiarity.

While the kinetic energy and prismatic imagery of Cwynar and Robinson’s films speak accurately to our current condition, it’s oftentimes necessary to pause and take stock of life’s less wearying developments. One of the pleasures of American veteran Ernie Gehr’s films, and in particular his late work, is his attention to the small moments and natural wonders that shape our day-to-day existence. At the vanguard of experimental cinema for much of his 50-year career, he now, at age 76, works on more modest but no less considered terms. His latest, Autumn, a 32-minute digital piece, exemplifies much of what makes Gehr’s films such a necessary reprieve from the white noise of contemporary life. (The same might be said of his contemporaries James Benning and Nathaniel Dorsky, each of whom produced equally contemplative new works this year.) Shooting in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Gehr quietly documents a rapidly changing topography in a few square blocks. The neighborhood’s many new windowed exteriors provide Gehr with myriad surfaces with which to work. Fixed camera perspectives belie the activity Gehr captures in any given shot: cars, pedestrians, and cyclists become his subjects as they casually pass through each image, their reflections rippling across the frame in subtle plays of light and shadow, producing multi-layered compositions that generate a depth and multiplicity of movement that our eyes often overlook. Gehr’s interest in people and how they not only define and activate space, but also shape the coordinates of a healthy and functioning society resonates deeply in these times of division and unrest. In a year when civil liberties were under constant siege, Autumn gently reminds us that humanity, in all its diversity, is the bedrock of shared experience. If there was a more beautiful document of America in 2017, I didn’t see it.

Additional Notable Works: Barbs, Wastelands (Marta Mateus); below-above (André Lehmann); Configuration in Black and White (Helga Fanderl); Delphi Falls (Mary Helena Clark); idizwadidiz (Isiah Medina); Look and Learn (Janie Geiser); On Generation and Corruption (Takashi Makino); READERS (James Benning); Saint Bathans Repetitions (Alexandre Larose); Strangely Ordinary This Devotion (Dani Leventhal and Sheilah Wilson).

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.