TCM Diary: Two from Kirk Douglas’s Century

Lust for Life

Kirk Douglas acts like Vincent Van Gogh paints: with bold strokes, dazzling colors, and displays of passion sometimes alarming to witness. Proponents of understatement may blanch at the raw emotion of his performances, but there’s no denying that Douglas—who turns 100 on December 9—withholds nothing from the camera. To see him play tortured characters is akin to watching Van Gogh in his wheat field, making manifest his demons on canvas.

For that reason, his portrait of the anguished Dutch painter in Vincent Minnelli’s 1956 biopic Lust for Life is both inspired and inevitable, the culmination of the private mania that had been simmering since his debut film, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers.

“I always worked on the theory that, when you played a weak character, find a moment when he’s strong, and if you’re playing a strong character, find a moment when he’s weak,” the actor has said. That layering of contradictions brings psychological complexity to every role he attacks. If his leader of a slave revolt against the armies of Rome in Spartacus is a study in martyrdom with palpable traces of pride, his Van Gogh exemplifies a fatally reckless yearning to be useful. In Douglas’s interpretation, the mighty are flawed and the flawed are mighty.

Lust for Life

Van Gogh’s all-consuming hunger for connection, which his own intensity obstructs, is brilliantly enacted by Douglas: the man whose paintings now fetch eight figures at auction could not find a steadfast friend in life, or even a consistent parasite. “I’m in a cage of shame and self-doubt and failure!” Vincent rails to his brother and benefactor Theo (James Donald), envying those with purpose and those content to be idle. Desperate to channel his impotent fervor into something constructive, he pours himself into faith, then love, then art. Each affords only short-lived fulfillment, as organized religion proves too strict for his indiscriminate humanism, personal relationships crash on the rocks of his obstinacy, and rank insecurity blights his self-expression. He craves the approval of colleagues like Paul Gauguin (Anthony Quinn), with whom he briefly cohabitates, but the macho Frenchman is repelled by his acolyte’s childlike need and perplexed by the anarchy of his work (“You paint too fast!”).

Minnelli, who began his career as a theatrical set designer, had a bold visual sense and a flair for color, as well as an intuitive grasp of artistic temperaments on screen and off. He and Douglas were ideal collaborators, and he stated that his star “achieved a moving and memorable portrait of the artist—a man of massive creative power, triggered by severe emotional stress, the fear and horror of madness.” Douglas practiced painting crows so he would appear credible at the easel, and he’s entirely persuasive in thrall to inspiration, holding his brush like a weapon and stabbing the canvas like he’s fencing with the storms in his mind.

In terms of outward sparring partners, Gauguin proves the most formidable. Quinn won an Oscar for his robust supporting work, but as spectacularly as he fares as a sort of proto-Hemingway—dispensing supercilious advice and dogmatic opinions, deploring sentimentality and unmanly displays—his performance owes much of its power to his co-star. Without Van Gogh’s obsessive hero-worship and acute loneliness, so movingly rendered by Douglas, Gauguin’s insults and rejection would carry no weight. Douglas conjures Van Gogh’s fogs and frenzies without vanity or inhibition (reflected in Miklos Rozsa’s dizzying score), but he’s equally affecting in moments of quiet vulnerability, as when he croaks to Theo that his attacks of hysteria leave him helpless, like a crab on its back. His relationship to self-harm forms a disquieting plot thread, as he condemns suicide as “terrible” and “unthinkable,” but in windows of self-awareness grows mindful of its inexorability.

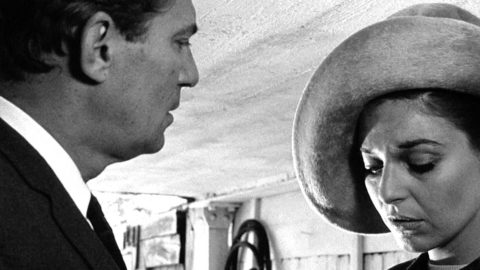

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers

Douglas the actor was mindful too—of his striking physical resemblance to his subject, of being the same age as Van Gogh when he scattered the crows with a shot, and of the degree to which he’d identify with the man, as one fervid artist to another. “I don’t want control! I’m after emotion,” Vincent proclaims to Gauguin; one imagines this role revealed to Douglas that one comes at the expense of the other.

The strength-and-weakness dichotomy within Douglas’s characters was evident from his introduction as Barbara Stanwyck’s alcoholic husband in Lewis Milestone’s 1946 noir The Strange Love of Martha Ivers. For the first 30 minutes before he appears, his character, District Attorney Walter O’Neil, functions as a joke: a bespectacled face on a campaign poster, described by others as “a scared little boy… [who] looks like he’s going to cry any minute” and a man “who’ll be whatever his wife wants him to be.” When at last we meet Walter in the flesh, he’s explaining to wife Martha (Stanwyck) why he got drunk and missed an important speech, which she had to deliver in his stead. He unfurls a monologue about his late father’s dreams for him that arrests the viewer’s attention. On paper it’s merely functional, but Douglas infuses it with putrid contempt and self-loathing; suddenly, the fourth-billed newcomer is in control of the film.

“Didn’t you see the blackmail in his eyes?” the paranoid Walter sneers of Sam Masterson (Van Heflin), a figure from their past whose return threatens to expose the secret that binds him to Martha. Walter discerns his wife’s attraction to Sam, and Douglas registers every twinge of jealousy; note how he fleetingly wilts upon learning that Martha stepped in to delay Sam’s departure. All of Douglas’s scenes involve Walter’s power relative to other figures on screen. He is emasculated by Martha, Sam, and even his secretary—only when grilling frightened fugitive Toni Marachek (Lizabeth Scott) does Walter have the upper hand. Douglas lets his eyeglasses symbolize his weakness; he takes them off to match wits with the daunting Heflin.

Out of the Past

Where another star would accept the role’s dimensions and leave Walter flat, Douglas instills him with remorse and depth of feeling—which, combined with the envy of a cuckold and the bitterness of an underachiever, have warped him into the man he’s become. As film historian Tony Thomas writes, “Despite the softness and unpleasantness of the part, Douglas made the man sympathetic. He gave his weakling a little humor and warmth, and the suggestion that under other circumstances he might have been a good and decent man.” All Walter ever wanted was Martha’s love and respect; he would’ve been content to marry her and never have to speak in public. Instead she wounds him with words of praise for his rivals (“Sam was always smart”) and he washes her ambitions down with bourbon. Their marriage is an Edward Albee play in miniature, marked by malicious games-playing and codependency—though not even Albee would’ve dreamed up the bizarre outcome of their toxic pas de deux.

Grinning at unwholesome developments, Douglas might’ve joined the fair-haired heels club that comprised Dan Duryea and Richard Widmark. (His next part, the perversely suave racketeer in Jacques Tourneur’s immortal Out of the Past, brought him even deeper into smiling villainy.) The actor famously swears by the axiom, “virtue isn’t photogenic.” Indeed not, but the flawed personages of Kirk Douglas, raging for redemption, are as bold and brilliant as the swirls of The Starry Night.

Lust for Life airs December 3, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers December 13, and Out of the Past December 21 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.