TCM Diary: Jane Fonda in the 1960s

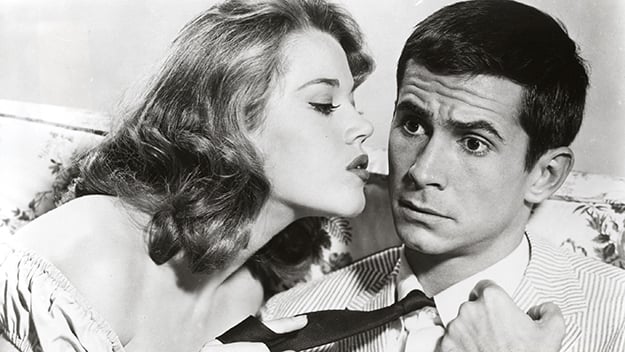

Jane Fonda and Anthony Perkins in Tall Story (Joshua Logan, 1960)

In the November 1960 issue of Pageant magazine, a bright-eyed Jane Fonda looks over her shoulder, her blonde hair pinned up in a small bouffant, her lips full and puckered. She’s 22 in this spread, fresh off her first screen role in Joshua Logan’s Tall Story, in which she plays a co-ed shamelessly in pursuit of a husband. Encouraged by Lee Strasberg, her coach at the Actors Studio since 1958, Fonda hungrily pursued a career as an actress in a time when changing sexual mores were trickling into the subtext of popular American cinema. “The American Bardot” reads one of the magazine’s headlines, a label that stuck to Fonda years before marrying Roger Vadim, the French director formerly married to the real-life Brigitte Bardot. Despite the comparisons, Hollywood (and later Vadim himself) downplayed Fonda’s beauty and sensuality, which supposedly paled in comparison to the French vixen and other blonde bombshells of the time. “I’m no [Marilyn] Monroe. There’s no point fooling myself on that score,” Fonda said to Pageant writer Martha Weinman, “And I’m not a beatnik. I feel fortunate in having a bit of everything, and—this sounds awful—I think I have a certain quality of class.”

This “quality of class,” which Weinman went on to describe as a compound of “intelligence, dignity, and the faint beginnings of arrogance,” was part of the reason young Jane so convincingly embodied the tensions facing women of her generation. With the ascent of second wave feminism and the sexual revolution, young women were caught in limbo between the values of the past and attractive new visions of the future. Fonda’s early work unspooled alongside these developments from her very first movie, and in the nearly decade-long period before the antics of Barbarella (1968) established Jane as a full-fledged sex icon, her roles in a number of sex comedies and racy dramas embodied the anxiety of American gender politics in transition. What’s more, she looked like an ingénue: baby-faced and rail-thin at the time, she didn’t pass for a freewheeling sexpot. This, and perhaps the “arrogance” and “dignity” of her pedigree as the daughter of a enormous star made her characters’ moral conflicts all the more convincing. “She’s not overtly sexy,” Logan observed, “but terribly, terribly romantic looking.” Like it or not, Jane Fonda at the start of the ’60s was a paragon of the mid-century woman’s sexual and moral ambivalence.

In The Chapman Report (1962), Fonda plays a guilt-ridden young widow, Kathleen, who nervously recalls her strained relationship with her recently deceased pilot husband as evidence of her sexual frigidity. Based on the novel of the same name by Irving Wallace, the film, directed by George Cukor, follows the sexual lives of four women living in the L.A. suburbs of Brentwood: Shelley Winters plays the adulteress, Claire Bloom the psychosexually deranged nympho, Glynis Johns the bored housewife, and Fonda a daddy’s girl disinclined to physical intimacy. Sexologist George Chapman (Andrew Duggan) and his assistant Paul Radford (Efrem Zimbalist Jr.) arrive in Brentwood to conduct a sex survey for which these women become case studies. Chapman (who is swarmed upon his arrival by reporters with questions like “Why do women marry?” and “Are men capable of sexual loyalty?”) is a riff on Alfred Kinsey and the Kinsey Reports—the studies published in 1948 and 1953 respectively that sparked discussions which began to question rigid understandings of sexuality.

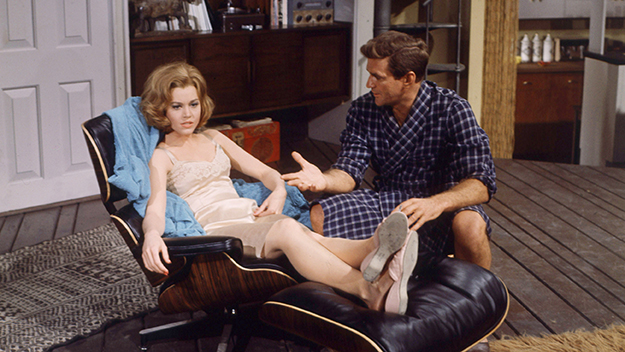

Efrem Zimbalist Jr. and Jane Fonda in The Chapman Report (George Cukor, 1962)

The Kinsey notion that heterosexual women could enjoy sex as much as their male counterparts was particularly suggestive, and it’s an idea that The Chapman Report encourages so long as these pleasures exist within the bounds of marriage. There’s something distasteful (though in keeping with the moment) about a film that so readily buys into feminine stereotypes tailored solely to a woman’s unique relationship to men. But the expressions of quivering, frustrated desire manifested by the four central performers register deep tragedy and easy humor in a way that pierces through Cukor and cinematographer Harold Lipstein’s clinical visual assemblage, clothing the women in color-coded attire against a melancholy blue backdrop (white for Kathleen, and brown for Bloom’s jezebel, for instance). Fonda’s character happens to have the most virtuous pathology of the four women; scarred by her emotionally abusive past relationship into believing she completely lacks physical desires, Kathleen pushes back against the notion that her love means less without a robust sexual component.

As the ideas proposed by Kinsey’s findings picked up steam throughout the ’50s, a number of developments loosened the Production Code Administration’s (PCA) grip on Hollywood. These changes fostered the rise of sex comedies featuring bachelor pad titillations and women playing things fast and loose—the sorts of films that defined, in large part, Fonda’s screen career up to and including Barbarella. One year after the Supreme Court ruled that motion pictures were forms of expression entitled to First Amendment protection, Otto Preminger and United Artists challenged the PCA for the right to incorporate at-the-time provocative verbiage in the script for The Moon Is Blue (1953). His film became the first Hollywood film to use the word “virgin” and the first to be released without the PCA’s seal of approval; 10 years later the social function of a woman’s virginity is at the very heart of Sunday in New York (1963), a screwball comedy directed by Peter Tewksbury (a Father Knows Best director making his feature debut) and written by Norman Krasna (in the second-to-last screen credit of a career stretching back to the 1930s and including Mr. and Mrs. Smith).

Jane Fonda and Rod Taylor in Sunday in New York (Peter Tewksbury, 1964)

As Eileen, a chaste young woman fed up with the toll of her sexual inexperience, Fonda received some of the highest praise in her career thus far, with critics noting her talents as a gifted comedienne. (Years later Pauline Kael described Fonda during this early period as a “charming, witty nudie cutie.”) When Eileen arrives at her big brother’s apartment in New York City, she bluntly raises the question of whether a girl should go to bed with a man before getting hitched. Beaus keep dumping her, she claims, because of her refusal. Appalled, brother Adam (Cliff Robertson) insists on his heart’s honor that this is definitely not the case, even as he himself regularly indulges in a philandering, bachelor lifestyle. But Eileen—thanks to Fonda’s candid, spirited presence—is no chump, and her perceived integrity has Adam tiptoeing around his pre-arranged Sunday tryst to conceal from her his own indecency. When she drops the virginity question in her opening monologue, Fonda’s voice booms fearlessly, conveying how fed up the character is with the “rules” of sex. For the remaining hour and a half, Fonda’s morals are challenged by the hypocrisy of her older brother and complicated by the entry of a charming man (Rod Taylor) she meets on a Fifth Avenue bus.

Three years later, Fonda graduated from frustrated virgin into reluctant mistress in Robert Ellis Miller’s debut film Any Wednesday (1966), which has Fonda’s sprightly Ellen seduced (not through the temptation of sex, mind you, but through a paid-for apartment and room full of balloons) by a wealthy, married business executive, John (Jason Robards). Initially Ellen rebuffs John’s advances, but appalled as she may be by his audacity in spite of his wife and kids back home, his sensitivity, persistence, and willingness to indulge her whims eventually lead to her capitulation. Like Eileen in Sunday in New York, Ellen is baffled and worn out by the intrepidly horny men around her, a predicament that allows Fonda to make excellent use of her maximalist performing tendencies: after her lover’s wife, for instance, suddenly appears at her secret apartment, Fonda confronts the man with screams and charged physicality. At the same time, Fonda plays a glamorous version of the modern New York woman so naturally—whether confessing to her fiancé her near-sexual tryst while the two slow-dance at a glitzy nightclub in Sunday in New York, or as a kept woman in Any Wednesday strutting around her Manhattan condo provided by her lover in a sheer negligee with comically long sleeves. Moral fortitude notwithstanding, the faint glimmers of Bree Daniels, Fonda’s anguished sex worker character in Klute (1971), are already perceptible.

Sunday in New York, The Chapman Report, and Any Wednesday air January 24 on Turner Classic Movies.

Beatrice Loayza is a film and culture writer based in Washington, D.C.