TCM Diary: Henry Fonda, American Statesman

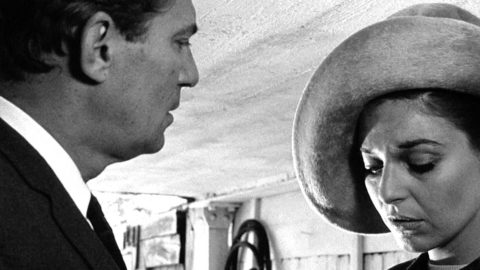

Advise and Consent

“I ain’t really Henry Fonda,” said the man whose iconic roles could inspire a second Mount Rushmore. “Nobody could be. Nobody could have that much integrity.” It’s a sobering thought, that the alter ego of Tom Joad, Young Mr. Lincoln, Juror No. 8, and Hollywood’s most upright Wyatt Earp could in fact have feet of clay. He was the first to admit it was true: “I’m not that pristine pure; I guess I’ve broken as many rules as the next fella.”

Yet by the 1960s, Fonda’s public identity was so well-established that his name had become shorthand for honesty and idealism, his blue-eyed visage a symbol of all that is aspirational and homegrown. Unlike John Wayne, Fonda seldom resorted to violence on screen, but his eloquence and wit made him a formidable foe. His plainspoken sanity could clash sharply and potently with the sinister machinations of others on screen, but in a more knowing, less babe-in-the-woods manner than that embodied by James Stewart or Gary Cooper. Whatever one’s political leanings, his presence on a ballot would be a comforting sight. And so, before closing out the decade with his sensationally image-demolishing turn in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, he made a series of politically themed films that cannily used the “Henry Fonda” brand to explore the futility of leading with one’s conscience in a realm that—like life itself—encourages compromise and capitulation.

Compromise is the order of the day in Otto Preminger’s 1962 Advise & Consent, based on Allen Drury’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, though few of the slippery, strong-willed senators on parade are willing to do any such thing. Fonda is Robert Leffingwell, an outspoken liberal nominated by the ailing U.S. president (Franchot Tone) to fill the vacant position of secretary of state, and uphold the chief executive’s foreign policy should he die in office. Leffingwell is said to have more enemies than any man in government, even within his own party—he opposed a power bill championed by junior senator Brig Anderson (Don Murray)—but especially on the other side of the aisle. His partisan foes see him as a Communist appeaser who will “lead us straight to perdition,” in the words of Seab Cooley (Charles Laughton), a knotted oak from South Carolina who may put latter-day viewers in mind of Strom Thurmond.

Advise and Consent

The senatorial hearing to determine if Leffingwell’s appointment will be confirmed supplies the catalyst for the film’s trenchant and still timely political panorama. Fonda is largely used as a figurehead, as the politicos played by Murray, Laughton, and Walter Pidgeon (as the principled Majority Leader) dominate the action. But one unspoken question hangs in the air from start to finish: how can it take nearly two and a half hours of screen time to approve Henry Fonda? How can Abe Lincoln, with 25 years’ added experience, possibly “weaken the nation’s moral fiber”? Is his transgression holding unpopular views—e.g., that diplomacy, not artillery, should be used against the Soviets—or expressing them in so rigid and scornful a manner (dismissing Cooley’s “outworn principles” and national pride as unwanted holdovers from the 19th century).

A subcommittee chaired by Anderson bombards Leffingwell with queries and accusations, issuing the expected ad hominem attacks. Then as now, public intellectuals are ridiculed by populist panderers who view intelligence as a dangerous thing in government; Leffingwell commits the dual-edged sin of admitting and making light of his erudition (“At this moment I’m in full flower of eggheadedness, and I hope to spread the spores of egghead everywhere I go!”). The bombshell drops with the surprise testimony of Treasury clerk Herbert Gelman (real-life HUAC “unfriendly witness” Burgess Meredith) that Leffingwell once belonged to a Communist cell bent on bringing the ideology stateside through violent means. (This episode was inspired by ex-Party member Whittaker Chambers’s denunciation of state department official Alger Hiss.) Though the clerk is discredited, Leffingwell clearly is withholding information, and when the omitted facts finally emerge—that he did indeed attend Marxist meetings as a cause-hungry youth, and recommended the hapless Gelman for his job in the Treasury to keep him from divulging their association—they come as a greater shock to the audience than the investigatory body.

Viewers in 2016 are likely more sympathetic to Leffingwell’s skepticism of capitalism as the be-all and end-all, but after decades of watching politicians self-destruct by bearing false witness in answer to non-criminal allegations, we wonder how Henry Fonda could be so imprudent. Yes, it’s Leffingwell and not Fonda who compounds an indiscretion with a lie under oath, but this brings out the film’s main point, and the reason for casting Fonda: even the righteous are tarnished. If this Midwestern pillar of decency is capable of bribery and perjury to save himself personal embarrassment, maybe Mark Twain is correct that there is no distinctly American criminal class except Congress.

The Best Man

Twain—perhaps in the same puff of cigar smoke—defined a patriot as “the person who can holler the loudest without knowing what he is hollering about.” That’s an apt summation of the fervid but hollow speechifying that echoes through the halls of a party convention in Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1964 The Best Man. The film finds Fonda once again seeking the support of fellow politicians, but this time, as if taking up the thread of Advise & Consent’s Leffingwell, his William Russell is the current secretary of state jockeying for his party’s presidential nomination. (Completing the triptych of ascent, Fail-Safe, released later in 1964, sees the actor playing a U.S. president desperate to prevent nuclear catastrophe.)

The most salient difference between the world of today and that of The Best Man, adapted from Gore Vidal’s 1960 stage play, is that a half-century ago political conventions were not faits accomplis but political open seasons, charged with suspense as high-level endorsements and backroom delegate swaps could tip the scales first one way and then another. Fonda’s Russell and Cliff Robertson’s Joe Cantwell are the leading contenders in a dead heat that can only be broken by the support of wily, Truman-esque President Art Hockstader (Lee Tracy, the best man on the 1964 Oscar ballot). Cantwell, a Richard Nixon/Joseph McCarthy surrogate, will stop at nothing to achieve his ends, paying no mind to Hockstader’s pronouncement that there are no ends, only means. Russell, more scrupulous, has the commander-in-chief’s admiration but not necessarily his backing—in a time of crisis, he may prove cerebral to a fault.

Advise & Consent and The Best Man bear surprisingly abundant and precise similarities, beyond the presence of Fonda as star. Whatever it reveals about national politics in the age of Camelot, both films feature a dying President, the Red Scare, a homosexual past dredged up as blackmail, fondness for bourbon and branch water (blame Tennessee Williams), and an “eggheaded” Henry Fonda. Vidal unmistakably casts his lot with the Ivy League-educated Russell, who, in his introductory scene, manages to quote Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, and Bertrand Russell. As the author’s mouthpiece, Russell is gifted with the screenplay’s most toothsome dialogue (“She’s the only known link between the NAACP and the Ku Klux Klan”), but it takes Fonda’s salt-of-the-earth charm to give these epigrams the quality of naturalism. (In the 2012 Broadway revival of Vidal’s play, John Larroquette evoked a self-satisfied civics teacher more than a statesman cast lovingly in the mold of Adlai Stevenson.) The candidates are so far apart in outlook and agenda that they seem to belong to different parties, but the dichotomy of the qualified-but-aloof policymaker and the disingenuously “relatable” prejudice-monger is a sadly perennial scenario.

The Best Man

Dogged by accusations of womanizing and a mental breakdown, Russell seems otherwise a paragon of patrician leadership—until he comes into possession of a rumor concerning Cantwell that would end his career regardless of its veracity. Hockstader implores him to ride the wave of scandal to the White House, but Russell retorts that “gossip instead of issues, and personality instead of politics” were just what he went into government to stop. Fonda masterfully performs the aggrieved ambivalence of a man who knows the country would be better served by his administration than the ruthlessly ambitious Cantwell, but who cannot shake the ends-versus-means conundrum.

To a certain point of view, Hockstader is correct that Russell’s vacillation on whether to incriminate his rival is a sign of weakness. To another—namely, those weaned on the faultless Fonda persona—it’s disenchanting to watch him consider a smear campaign, whatever his reasons: it feels like the betrayal of three decades of cumulative trust, and an affirmation that no one—literally no one—can fight clean in the political arena. Fonda manages to suggest the paradox of decisive reticence, making us wonder however briefly whether a divided conscience is comparable to an absent one, and also supplying the best answer we’re likely to get as to why the noblest challengers are eliminated on the second ballot. “Power is not a toy we give to good children,” Hockstader asserts. “It is a weapon. And the strong man takes it and uses it . . . Because if you don’t fight, the job is not for you. And it never will be.” It takes Henry Fonda to show us that it’s not the best man who wins, but the last man standing.

Advise & Consent and The Best Man air November 7 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.