TCM Diary: The Great Man

When a pop culture luminary dies, the media tends to “print the legend”—to quote the famous line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—but in only an abstract form. Too many facts might cloud our vision of our white knights. But what happens when the great man was a heel?

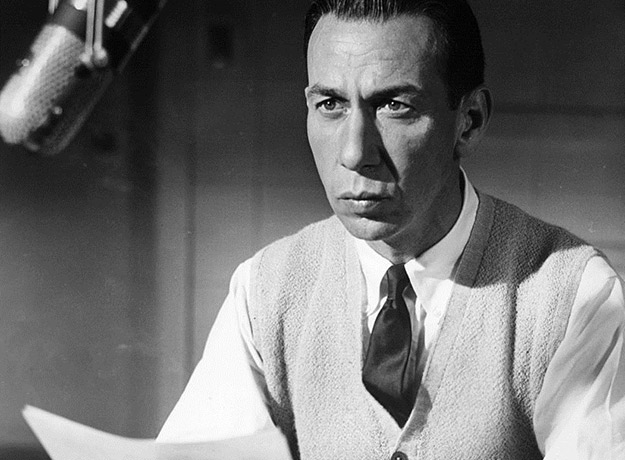

In The Great Man, that’s the conundrum facing Joe Harris (Jose Ferrer), a reporter tasked with assembling a crowd-pleasing tribute to renowned broadcaster Herb Fuller after his sudden death. As Harris speaks with those who knew the man best, a Citizen Kane–esque collage emerges of Fuller as an alcoholic narcissist whose greatest talent was convincing the public (“the great unwashed”) of his sincerity while caring only for fame and its spoils.

Based on a novel by Today Show producer Al Morgan (adapted with Ferrer into the 1956 screenplay, which Ferrer directed), The Great Man draws loose inspiration from the contrast between real-life TV legend Arthur Godfrey’s warm public persona and behind-the-scenes reputation for being autocratic and spiteful. (Godfrey’s folksy bonhomie and colossal ego also inspired the character of Lonesome Rhodes, Andy Griffith’s cracker-barrel demagogue in Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd.) A rare crack in the polished facade occurred when Godfrey abruptly fired 23-year-old singer Julius La Rosa, a regular performer, on air. (Godfrey would tell the press he had dismissed La Rosa because his protégé had “lost his humility.”)

True to Godfrey’s coarseness behind the scenes, Fuller’s dying word in The Great Man is an epithet with none of Rosebud’s mystery. Though Fuller kept his womanizing, payola, and drunken vandalism under wraps, his death occasions nothing less than a mass confessional to Harris, who merely wants platitudes for his network-commissioned snow job. Instead, as he questions Fuller’s intimates one by one, they proffer harrowing accounts of the late icon’s rampant ambition. These scenes are as acridly cynical as any contemporary media exposé: producer Keenan Wynn recounts an act of journalistic malfeasance even more shocking than the climactic revelation of Broadcast News three decades later. Only Fuller’s bandleader and radio family (based on Arthur’s sidekicks, “the Little Godfreys”) give Harris anything usably pleasant, though they clearly intend to ride the wave of sentiment for Fuller to greater career heights.

The most affecting witness is Harris’s mistress, Carol Larson, a boozy singer played brilliantly by ’50s chanteuse Julie London (“Cry Me a River”). With the slurred cadence of a drunk determined to get her story out, London’s voice cracks with emotion as she chronicles her abusive history with Fuller, just as vulnerably as it does in song. At one point, the morose Carol, by now deep in her cups, accompanies her own (sober) performance of a torch song on the radio. Beyond showcasing London’s mastery of two crafts in the same frame, the effect is indescribably poignant, situated as it is in Carol’s piteous plea to keep the same rotten arrangement with Harris should he inherit Fuller’s crown.

Everyone in The Great Man‘s cynical world more or less knows the score, above all Harris, whose key conversational maneuver is to disdainfully parrot back the words he’s just heard (“Are you with me so far?” “So far.”). But he and his girl-Friday secretary (pert Joanne Gilbert) choke on their own vitriol when they’re faced with the one decent human being who drops into their orbit: Paul Beaseley (Ed Wynn), the owner of a Christian radio station in Worcester, Massachusetts, who gave Fuller his first job. At first mocked by Harris for his silly voice and provincial air, Beaseley explains very cannily that he understands people find him ridiculous, but as the vignette unfurls, he reveals himself to be wise to human nature and protective of people’s illusions. When he speaks of shielding his fragile wife from Fuller’s transgressions, he makes plain that we are a nation of “Mrs. Beaseleys,” desperately needing to believe in the ersatz goodness of strangers like Herb Fuller while flouting the genuine goodness of ordinary men like Paul. Wynn—a baggy-pants comic who enjoyed a late-career renaissance as giddy old men in Disney films (and whose son Keenan plays Harris’s boss, perhaps the biggest SOB of all)—is ideally cast as a man whose function is to throw the jaundiced world the characters inhabit in sharp relief, then return to Worcester and leave them to their cesspool.

The fat-cat executive played with steely authority by Dean Jagger explains in terms that haven’t aged a day that TV is a business, not an art form: “We’re selling time to sell personalities that in turn sell products. It’s as simple as that!” Even the ending of this jaded work is tinged with cynicism, finding that integrity moves product too, and can be monetized as readily as corruption.

* * *

In an odd coincidence, The Great Man (which seldom sees the light of day apart from occasional airings on Turner Classic Movies) was evoked by TCM host and critic Ben Mankiewicz in his written tribute to Robert Osborne, the cultured face of that network who died March 6. “The movie works,” Mankiewicz explains, “because in our minds, if not our hearts, we know that we’re capable of deifying the dead, turning flawed human beings into heroic titans of virtue and justice… However, there are times when the truth requires no creative license. And this is such a time—Robert Osborne was a great man.”

No one will challenge that statement. For cinephiles of all ages but especially those of us who precede the streaming era—weaned on real-time broadcasts presented “uncut and commercial-free” on TCM, bookended by genial narration—Osborne was classic movies, and they were he. To this day, whether I’m in a theater or watching a Blu-ray or streaming, when a Golden Age film ends I expect Osborne to come strolling out and tell me something I didn’t know about the production, the stars, or where the movie fits into the big picture of Hollywood. No film on TCM felt entirely complete without an anecdote from him, specific and fresh as they always were—not some piece of trivia but a story, dovetailing with others he’s shared to form a complex oral history of the narratives that engender narratives.

Osborne was the laureate of Hollywood lore, the eloquent Virgil of the Dream Factory. In his case, you can print the legend, because it was true.

The Great Man airs April 23 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.