SXSW Interview: Eugene Kotlyarenko

You can understand a lot about an era through its technologies, but even more through its diseases. In the 19th century it was hysteria; today it’s anxiety and depression. Although this is not to ridicule the suffering of people who suffer from either (or both), it’s been proven that smart phones and social media do increase stress, make it harder to fall sleep, and feed into negative feelings. This shared modern disorder—and how it impacts love, communication, and lust—is explored in Eugene Kotlyarenko’s funny and critical Wobble Palace. On the eve of the 2016 election, Jane (the talented Dasha Nekrasova) and Eugene (played by but definitely not an exact stand-in for Kotlyarenko), a longtime couple, are on the verge of breaking up, and agree to split their house over Halloween weekend. Since they’re already in an open relationship, both pursue different sexual conquests: Eugene plays around on (and gets played by) Tinder, and Jane enjoys the company of Ravi (Vishwam Velandy), a wealthy digital entrepreneur who’s closer to Patrick Bateman than Richard Hendricks. Without ever being dismissive or cruel, Wobble Palace faithfully shows the bitter truths about our gameified culture. I spoke with Kotlyarenko in the lobby of the Omni Hotel.

SXSW is a festival that really came to prominence because of films yours: low-budget, no stars, dealing with romance. Yet your film sticks out this year because it’s one of the few narrative features here that doesn’t have any stars in it. It’s set in L.A., but it isn’t dealing with the type of L.A. we usually see. How do you feel like you have navigated this festival and gotten attention for yourself?

My last film, A Wonderful Cloud, premiered here, and that was my first time here, and it’s, in a lot of ways, the best festival for my type of movie. I think the audiences here and the programmers here are really good and they’re willing to receive stuff that’s challenging but engaging. I don’t know what films you were thinking of, but I don’t think of a festival brand when I’m thinking about lineage. Sometimes I think, “Am I making real movies?” Like if a random normie sees my movies, will they think this is a real movie? The cool thing about going to festivals or when you get a limited release is that you meet real people who aren’t filmmakers or film heads or “film Twitteratis,” and they have all responded really well to this film and to the last film. So that’s what’s nice about it. I don’t know how to navigate stuff. I’ve lived in L.A. for 10 years. I wanted to “make it in Hollywood,” but during the majority of that time, no one seemed to care. I got a lot of “no” from a lot of people about things I worked on a ton, so eventually you have to say “yes” to yourself, and I think that’s sort of what independent filmmaking comes from, the necessity to make something. Necessity is the mother of invention, and hopefully people feel that energy that it’s unstoppable or incessant or annoying but annoyingly energetic.

I’m not the most creative person in the world, but I try to think about my favorite movies and what they did: what did they activate in me, and what were they doing in their cultural moment? Then I throw that away and ask what can I do to activate those same feelings in me. What can I do to grapple with what we’re going through now, culturally, in technology, communication, identity, gender, politics? All of that’s in the air. If you do that, someone’s out there listening and you have to have faith in that. Otherwise, write in a journal, write in your diary and maybe pray it’s posthumously published and your name is sung to the heavens.

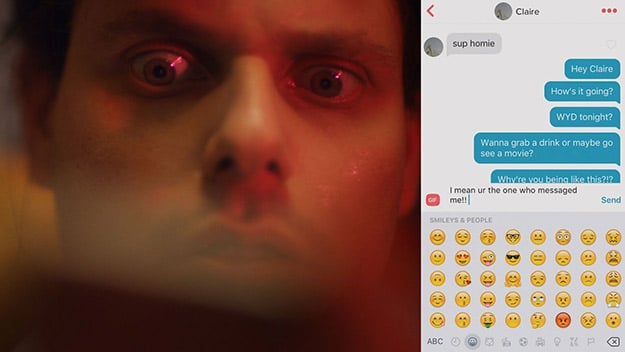

That’s really dark, but fair. I love that you get into things like how a really lonely person can become completely irrational when they’re rejected on Tinder, and the film opens with this great sequence of a scroll through old text messages between Eugene and Jane. How did you arrive at representing screens like this? A lot of our lives is that scroll, and but a lot of people don’t seem to realize that.

This stuff has been on my mind forever. This aesthetic and these ideas about screens, computer screens, and now our smartphone screens, is the way I’ve been working since my first films. It was pretty obvious to people who cared about movies in the early 2000s or late ’90s that movies were feeling less and less central since the computer started taking over. How do you deal with the screen, what is the screen culture that we live in? It’s—I don’t want to say “sickening,” but it’s a little bit disrespectful that any filmmaker trying to examine contemporary life would ignore that. Most filmmakers willfully do, and honestly the best filmmakers, the ones I respect the most, are often making period pieces now because they don’t know how to deal with that. I don’t need to name names, but I’m sure anyone who reads this knows what I’m talking about.

I wish that those people would deal with our moment, and I guess that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to say I know people have anxiety about their phones, I know people look through their text history with their exes or their partners, looking at where things went wrong or feeling nostalgia for when it was good. I know what it feels like to swipe right 100 times and never get a match, and I know that whether you’re my age or a 15-year-old or a 55-year-old, everyone’s dealing with a totally new world. And it’s not as new anymore.

It’s funny to do it on set, because we had a great DP, Sean Price Williams, who shot Good Time and Frownland, which is actually one of those movies that I look to as being a seminal significant film from the last 20 years. So I said, “Here’s the rough storyboard, leave a third of the screen with negative space,” and he asks “What, why?” “Because I’m gonna put a phone here.” Sean is a Luddite; he has a flip phone. I said, “There’s going to be a screen capture of my phone so that when people are watching me act a fool they’ll see what’s going on.” And he’s like “Okay?” and everyone on set’s like, “What the fuck, this is going to be so boring.” I told them just trust me guys, this is going to make sense. When you’re getting paid 10 million dollars and you have a star wagon trailer you don’t care, but when you have a very small budget and you’re standing there in a dinky-ass room and you’re on your phone, people wonder why you’re wasting so much time on this. That Tinder scene has proven to be, with audiences, one of the most successful sequences. Because people are there in the silence—the movie is a lot of talking and doing, and that’s one of the more silent, nonverbal things, and people are gripped. When he explodes, they all explode. People are cracking up and gasping. And you’ve seen those Tumblrs or Instagrams where women gather together all of the toxic horrible messages that they receive from men. I think many men have felt that, and most restrain themselves from acting on it, but a lot of them do act on it because they’re ridiculous and dumb. Well, they’re not dumb. It’s just that our minds and our emotions and our psychology haven’t evolved in the last few thousand years to deal with this instant communication, this instant gratification we now expect and get from our tech. When you have a person on the other line, especially if it’s through an app rather than someone you know, they’re an extension of the app, and the way the app works is that you have an expectation to receive an instant gratification so when that person, aka the extension of the app, doesn’t respond right away, you get angry.

I think what you’re touching on is important. Apps are made to plug into our brain, and they do in ways we don’t acknowledge. There’s all this science around user experience and user design, and making sure that all these things are “intuitive,” but there’s no recognition of the fact that what it taps into could be something really ugly. All those Reddit r/relationship threads where a woman talks about discovering that her boyfriend harasses black people online are sort of an example. Would that guy do that if he didn’t have the technology to do so? Would he be “brave” enough to harass people in real life? It’s kind of an impossible question. But it’s something that comes up again and again because we are living in this increasingly mediated world.

I would call it a gameified culture. I think about the way these apps are made to be as gameifying as possible, and that’s a dangerous thing when you apply it to love. That’s kind of what the movie is about in one way: that these emotions and these feelings that were formerly allowed to live in a vacuum, for better or worse, are being assaulted from all sides by these games of love and lust and fucking around. It’s complicated and it’s twisted, and I don’t want to say unhealthy, but it definitely deteriorates the social fabric and the emotional fabric that our society’s been built on for at least 150 years. We are going through this revolutionary moment and technology is mutating in this way, so the film is about those things that a lot of people are dealing with, and I hadn’t really seen a movie deal with them.

I want to also talk about sound design. I feel like you’re doing a lot of interesting things visually but you’re not forgetting the power of ambience. Like in the Tinder rage scene, there’s this hiss that comes up, and you can feel his anxiety in a different way.

For me the soundscape is really important. The number one thing is that the actors I’m working with have great voices. I think Dasha has a great voice, and Vish, who plays Ravi in the film, has an awesome voice, as does her friend played by Elisha Drons. Every date I go on, they all have this distinct way of talking, which is really important in a film that is half driven by a bunch of lines that I give them and improved by improvisation. They each have different character. The soundscape of voices is really important to me, and it’s something that I think about when I’m casting. You can hear someone’s intelligence in their voice, in the way they talk and just the tenor of their voice, the confidence, which means that they really are that person, or the wavering quality means they are that person—but is it the right type of wavering?

The “Wobble Palace” in the film—the house they live in—is like a computer. You have all these windows printed out on curtains, and the couch isn’t really a couch, but the type of couch you might see in a Tron world.

The house was designed by my ex-partner, with whom I lived in that house. The origin of the movie has partly to do with the relationship that she and I had together and the fallout from that, and partly to do with things that Dasha had gone through and things I was noticing. I’m not portraying her, and Dasha isn’t her; the Jane character isn’t my ex, but she built that house, we designed the IMs and stuff—we were finding that together. My ex-partner was really into it, because she’s a production designer and she has to do a lot of projects where she doesn’t really fully get to express herself because they’re commercial. She’s super talented, and she was into the project until she wasn’t. We called where we lived “Wobble Palace,” because it felt like an unstable place, and it turned out to be one.

I hope she sees the movie. I don’t think that the character that’s partially synthesized from my experience with her portrays her in a way that’s negative or insulting. I think it’s honest. Did you feel like the film shits on the female character? What do you think?

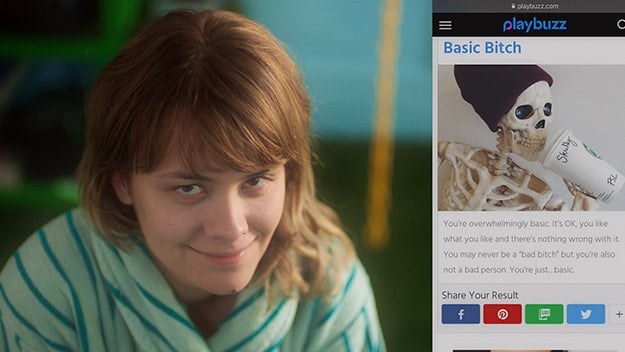

No, I don’t. I think the anxieties she has are interesting, largely because there is so much roleplaying in the film. There’s the actual sexual roleplay, which is very funny, but there are times when she worries about being a “basic white girl,” and then she takes a quiz with her gay friend and they find out she is a basic white girl, and then he has to comfort her. There’s a kind of cultural theft going on where she can try on these different personas for whatever situation she’s in, or complain about white people despite being white herself, but there’s no other option for her.

There’s no escape. The meta acknowledgment isn’t good enough, because of the skin and socio-economic situation that you’re in. It was important for me to try to figure out that anxiety because to me it’s pretty obvious that the anxiety of a single man or a man that feels trapped in his relationship is the anxiety of gaining approval and lust by getting your rocks off. All of these characters are characters. The danger in making a movie of this budget and style, which I often despise, is that it doesn’t feel like they’re creating interesting characters, they just feel like one bland voice after another. The Jane character is a synthesis of a lot of different people, largely Dasha—she brought so much to the table.

You say there’s lot of roleplaying going on and I feel there’s a lot of roleplaying going on in life: we’re constantly projecting identities out there to be proved or rejected, and actually any form of expression now, because it is so easily scrutinized by anyone in the public sphere is a role-play. Working through those ideas and those anxieties, between the inner human and the projection of that inner human into the world, is extremely tense and highly negotiated nowadays. I was trying to convey that. I think that’s obvious with my character, too, because he’s much more extroverted than Jane. She has an interiority that you access through the voiceover. My character is transparently a farcical fool who has the tragedy of occasionally being aware of his horrible selfishness, ego, and misogyny. One thing that’s annoying about some of the reviews that I saw is that they don’t presuppose that the film has an awareness of these things, which is so front and center in the satire and the farcical nature of these delusional characters. We all are delusional, having to negotiate this stuff. The disjunction between our interiority and exteriority is frightening, and apparent, so transparent to me when I interact with 99 percent of the world.

This is something that I come up against a lot—not just because this is a film/tech/music/brand festival—but because of what the work here is showing. In addition to everything being mediated by screens, we seem to be living through this really jarring cultural shift away from “hard work gets you something” to “anxiously projecting the right image gets you something.” There have always been myths around wealth and the idea that, for example, Dale Carnegie worked really hard to get to the top, and if you’re an exceptional person who puts forth an exceptional amount of effort, you too can succeed. But we keep seeing that’s not true. I can’t help but think of the exposé about the workers at Disneyland—those people work extremely hard, but have been reduced to living in their cars. It’s appalling, and it so clearly has nothing to do with a lack of effort or carelessness on their part. Meanwhile, people who look good because they’ve had a ton of plastic surgery can make money on Instagram through skinny tea and waist trainer endorsements. There are moments where technology gives us the illusion of being free of the past, but actually we’re just heading to something worse.

I think by this point anyone who isn’t sociopathic probably realizes technology’s not for them. I don’t want to say it’s a trap, but it’s certainly complicated, and I think people are going to at least be grappling with it for the next few generations. You were saying hard work is kind of out of vogue and this negotiation between having the right identity projected is what gets you to the top, but in the value system that we have all bought into, even smart people, that is the hard work, the projection. We are now living in a smart actor’s world. Someone like Marlon Brando or Jack Nicholson isn’t a genius. They are extremely talented actors who also are interested in architecture. Actors are good because they get passionately interested in things, not because they’re PhD scholars—not that PhD scholars are inherently so smart.

One funny anecdote: when she first got here, Dasha was on her way somewhere and was ambushed by InfoWars, and they came up to her and asked her “What do you think of Bernie Sanders?” and she’s the biggest Bernie Bro I know, and she was put on the spot. You know how this kind of conspiratorial, super-right people in their power suits come up to you and have already prepared all the ways to destroy you. And Dasha just did so perfectly, because she is a brilliant actress, because she is super intelligent, threw all the right shade and gave the funniest responses. She came back and said, “I have such bad anxiety, they’re going to edit it so I look like an idiot.” They posted it a few days later, and she comes off so well. She says, “You people have worms in your brains.” They ask what she likes about Bernie Sanders and she says, “His policies.” And they ask “Like what?” and she says, “Like ‘Eat the rich.’” She killed it. The Internet’s really behind her right now and I’m excited, and if she doesn’t get a lot of opportunities and roles from Wobble Palace, she’ll probably at least get them from that InfoWars interview.