Surface Funk: On Manny Farber

The following essay is from Manny Farber: Paintings and Writings, edited by Michael Almereyda, Jonathan Lethem and Robert Polito, and published by Hat & Beard Press.

Manny Farber in his Warren Street studio, New York City, 1970.

Photographer unknown. Images courtesy of Hat & Beard Press

Not long ago at the Hollywood Theatre in Portland I saw Nashville projected on a gloriously large screen with an enthusiastic audience. I had seen it many times before but now I was watching it with Farber’s take on the film fresh in my mind. He doesn’t fall into the world and characters easily, the way I seem to. The songs don’t tickle his funny bone or break his heart. Where I see Altman’s wide-ranging cast of characters of varying ages, social positions, and body types, Farber sees “single-note stereotypes” and “smug, pat predictability.” He sums up: “Nashville is a promiscuous movie that will go for anything to make a sensation.” The critique (written with Patricia Patterson) got me considering Altman through a new prism: “a Svengali of surface funk.”

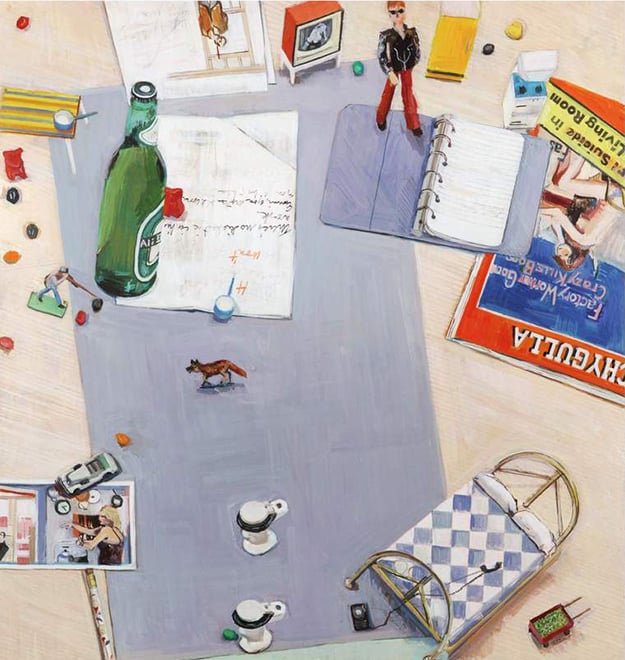

Lately, Farber’s paintings have me considering my desktop. His table-scapes are way more fun and mysterious than the stack of bills and to-do lists I’ve got laying around. Farber has railroad tracks that split and circle around making his desk a great expanse. He has lollipops and Tootsie Rolls, tiny neighborhoods, a few dead bodies, a dog trekking across the plains of his desk, and a train track that just breaks off. He has land-locked boats, grounded airplanes, cars parked on spiral-bound notepads. For all we know, the dog may be carrying a message. God knows what that train is hauling. Bright colors section off one area from another. His desktops are like a board game version of Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday, or the last quiet moments of normal, small-town life before Peckinpah’s men jump into action. You can almost hear the far away sound of children playing.

Manny Farber, The Films of R.W. Fassbinder, 1977, oil on paper

Farber can be a straight shooter: “Antonioni’s aspiration is to pin the viewer to the wall and slug him with wet towels of artiness and significance.” Sure, that’s clear enough. But just as often, Farber’s ideas, like his train tracks, just run out. The more times I read “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art,” the less sure I am of what he’s actually getting at. Usually if someone identifies something with the preamble termite-fungus-moss or slag blanket, you pretty much know where he stands. But with Farber, that’s not always the case.

It’s hard for me, as a filmmaker, not to internalize his words. The moment I’m feeling good about not having ambitions for gilt culture, I’m knocked back by the fear I’m involved with squandering-beaverish endeavors. Part of the pleasure of reading Farber (maybe now more than ever considering the I-got-a-million-Likes world we live in) is not knowing what he likes or dislikes. Likes and dislikes seem beside the point.

In both his paintings and his writing, he’s littering the floor with visual ideas. He unwraps an idea, throws it down, and is on his way. What’s he getting at? What’s that gun doing up there in the corner of his still life? For me, Farber’s sentences read like a long ash hanging off a cigarette that drops and, instantly, a new ring of fire begins. To his credit, probably, he reveals little emotion—he just lays his sentences down with a cool cat shrug. I see him as something like the Keep on Truckin’ guy and yet, to his mind, Altman is the Svengali of surface funk. Coming from Manny, this may be a high compliment.

Kelly Reichardt’s films include River of Grass (1994), Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Night Moves (2013), and Certain Women (2016). She is an artist in residence at Bard College.