Sundance Dispatch: Never Rarely Sometimes Always

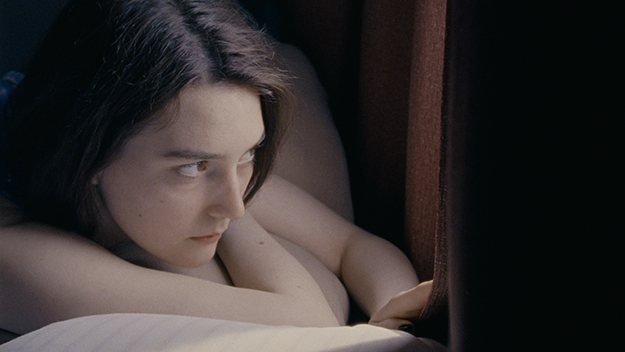

Sidney Flanigan in Never Rarely Sometimes Always (Eliza Hittman, 2020)

Eliza Hittman’s first two features, It Felt Like Love and Beach Rats, are evocative coming-of-age tales, attuned to the ways in which the pressures of gender and sexuality encroach, often destructively, upon adolescence. Her new film, Never Rarely Sometimes Always, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last weekend, starts off in similar territory: Autumn Callahan (Sidney Flanigan), a quiet, guarded high school senior in rural Pennsylvania, discovers that she is unexpectedly pregnant. The revelation is relayed with Hittman’s characteristic economy and attention to detail: in three swift scenes, Autumn examines her slightly protruding belly in the mirror, gets a pregnancy test at a local clinic, and then returns home and pierces her nose in a wordless assertion of her autonomy over her body. But as Autumn embarks on a quest for an abortion, this portrait of fraught teenagehood soon turns into something more overtly political than any of Hittman’s previous work: it becomes an intimate encounter with the state of women’s reproductive rights in the United States.

During a chat at a restaurant in Park City the day after the premiere, Hittman told me that she began writing the script in 2012, after hearing of the tragic case of Savita Halappanavar, a 28-year-old woman who died of septicemia in Ireland after being denied a life-saving abortion. “I read about how women traveled from Ireland to London and back in one day at that time,” Hittman said, “and I thought, how far would this woman have had to travel to save her own life?”

Never Rarely Sometimes Always charts a similar journey in microcosm. Unable to get an abortion without parental consent in Pennsylvania, Autumn takes a bus to New York City with her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder) to seek help at a Planned Parenthood office. Hittman emphasizes the contrast between the girls’ small, quaint hometown and the terrifying, overstimulating bustle of Manhattan, which throws umpteen hurdles at them, from confusing train routes to predatory men. “I was fascinated with how quickly the world changes when you leave New York City. You drive two hours and you’ve traveled back in time,” Hittman said.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always bears obvious parallels to 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Cristian Mungiu’s 2007 thriller about two college students seeking an illegal abortion in the final years of Communist Romania. Hittman acknowledges the film as a reference, but says that she was inspired by her grievances with it. “I think it’s a film that is masterfully executed, and yet it left me wanting so much more from the female character who was actually pregnant. I felt that her representation was somewhat misogynistic, because she’s depicted as being really naive and careless. I didn’t find it empathetic toward her,” she said. “I wanted to make a film about two women in a similar predicament that was really empathetic to both of their journeys.”

The comparison between the two films underscores the ironies that make Never Rarely Sometimes Always such a sharp and timely critique. For the women in Mungiu’s film, the only option under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s conservative regime is an illicit abortion. In Hittman’s film, safe and legal abortion is available to Autumn (in another state), but she still faces tremendous difficulties that stem from internalized stigma and the lack of infrastructural support for women who make that choice. She is unexpectedly forced to stay in New York for three nights to complete the procedure and, too proud to accept the clinic’s offer of shelter and too scared to use her parents’ insurance, she and Skylar end up stranded in the city with no money and nowhere to sleep.

Hittman leans into the bureaucratic nitty-gritty of procuring an abortion, which she based on conversations with social workers and abortion providers and visits to pregnancy clinics in both Pennsylvania and New York. “For me, it was about all of the real-life obstacles that someone would encounter,” she said. “I’m interested in narratives that are about human obstacles.” One of these obstacles in the film happened to be unscripted: when Autumn and Skylar arrive at the Planned Parenthood in Brooklyn, the sidewalk is crowded with actual anti-abortion protestors, who had showed up for their weekly demonstration on the day of the shoot.

The most powerful moment in the film, however, is not one of confrontation but of self-realization. In a preparatory interview with a Planned Parenthood counselor, Autumn is asked about her experiences with intimate partner violence and sexual assault; in her answers, she’s asked to choose between the options “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” and “always.” As the questions get more and more personal, Autumn’s face—fiercely stoic for most of the film—begins to contort in confusion and pain; an understanding of her own experiences dawns upon her, elucidated perhaps by the clinical language of the questionnaire. It’s an extraordinary feat of acting by newcomer Flanigan, who is filmed up close in a single, simmering long take.

“I decided early on that we would attempt to do it in a long take,” Hittman said of the scene. “A lot of times when you see films with first-time actors or non-actors, there’s a feeling that the performance is cut, it’s edited, because they’re not a real actor. But with Sidney, I knew that she could do it in a long take, and I knew that it was all about actually spending time in the office. The idea was to create a little bit of intimidation and pressure on her as a human in the moment to intensify the experience.” Hittman also recruited an actual counselor from a clinic in Queens to perform in the scene. “I thought she could take Sidney through it organically and create a space for her to feel vulnerable. If it was two ‘actors’ acting, I don’t think it would have the same effect.”

The scene calls back to the film’s opening sequence, in which Autumn mournfully performs a cover of “He’s Got the Power,” an uptempo hit by the ’60s girl group The Exciters. Captured in Hélène Louvart’s luscious, grainy 16mm cinematography, the song and the scene—which also features a retro dance performance and an Elvis impersonation—evokes a sense of being “trapped in time,” as Hittman put it. This hint of anachronism pervades the whole film, underscoring the failures of the American healthcare system and the fact that, in Hittman’s words, “the country just seems to be rolling things back.”

It’s a sentiment that felt especially urgent last Friday, when the film premiered in Park City just hours after Trump became the first sitting president to speak at the annual “March for Life” rally in Washington, D.C. To describe Never Rarely Sometimes Always as a PSA seems to cheapen the empathy and scope of Hittman’s film. But given the times we live in, Autumn’s plaintive cry against the patriarchy through that opening song’s lyrics—“He makes me do things I don’t want to do / He makes me say things I don’t want to say”—feels like nothing short of a wake-up call.