Sundance Dispatch: Midnight Family & The Infiltrators

Midnight Family (Luke Lorentzen, 2018)

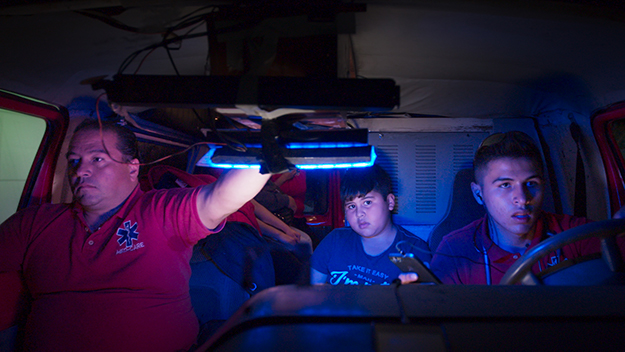

There’s a scene in Luke Lorentzen’s Midnight Family that has all the trappings of a high-octane action-movie chase sequence. The Ochoas—patriarch Fer, and sons Juan and Josue—race against another vehicle through the neon-lit streets of Mexico City. The teenaged Juan is at the wheel, cutting haphazardly through traffic; Fer yells out directions, shouting at passersby to get them out of the way; and the nine-year-old Josue sits in the back, whooping and cheering, “We’re gonna win!” It all seems like an adrenaline-thumping adventure—until you remember that you’re watching a documentary, that the Ochoas are driving an ambulance, and that they’re trying to beat another ambulance to the scene of a terrible accident.

It’s this peculiar world that Lorentzen attempts to capture in his rich, attentive second feature—the world of “free market healthcare at its most complicated,” as he puts it in a Skype interview before the premiere of Midnight Family at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. His subjects, the Ochoas, operate one of the many private ambulances that attempt to alleviate (and profit from) Mexico City’s distressingly skewed ratio of 45 public ambulances for 9 million people. It’s a precarious business steeped in corruption—the Ochoas are untrained and uncertified, and they bribe the police to get ambulance calls directed to them—and it’s made even murkier by the fact the Ochoas’ own survival depends on finding patients desperate enough to need them and wealthy enough (and willing) to pay them.

Most of Midnight Family is confined within the Ochoas’ ambulance, with Lorentzen, a one-man-crew, documenting their nightly grind in all its lulls and thrills. Lorentzen’s camerawork—which won a Special Jury Award at Sundance—is strikingly classical, in spite of the cramped space and the frenetic pace of things. Each frame in Midnight Family is beautifully lit, which the director attributes to Mexico City’s vibrant urban lightscape; it’s also a patiently composed film, with Lorentzen often isolating the main characters in lush wide shots, using a single prime lens mounted in front of the ambulance. “I always wanted the viewer to experience the ambulance as something they were riding,” he says, “and keeping the lens consistent puts you in a place and keeps you there.”

That sense of static, bounded perspective makes Midnight Family both “a sensorial and an ethical rollercoaster,” as Lorentzen describes it. His camera takes us into the inner life of the Ochoas, drawing us into their hopes, worries, and often endearing banter; it also offers a remarkably unfiltered glimpse into the escalating compromises they make to stay afloat in this business. First they’re cutting corners by avoiding some of the more expensive equipment; soon, they’re redirecting patients to farther-away hospitals that pay them a commission, which backfires troublingly towards the end of the film. Lorentzen says he struggled with his role as a documentarian while filming these scenes. “It’s the eternal dilemma of filming problematic things,” he says. “What could I have done, if anything, and was the story that I captured as a result of perhaps not doing anything worth it?”

Ultimately, he was convinced, he says, that “the Ochoas were good people trying to survive in a broken system.” That’s certainly the impression one gets from Midnight Family. The most affecting scenes in the film are of the Ochoas interacting with patients. They’re genuinely caring and tender, whether while resuscitating the unconscious baby of a broke junkie or comforting a victim of domestic abuse. By capturing the little negotiations that undercut their kindness—their attempts to figure out, for instance, if the abused woman comes from a “fancy” family—Lorentzen gets us uncomfortably close to the moral, emotional, and social consequences of a fast-corporatizing world.

The Infiltrators (Christina Ibarra and Alex Rivera, 2018)

The specter of privatization also lingers in the background of The Infiltrators, an inventive docudrama set in and around an ICE detention center in Florida. Adding insult to the plight of the detainees at the Broward Transitional Center, many of whom are refugees and asylum-seekers, is the fact that they’re held in a for-profit institution run by George Zoley’s GEO Group. Each additional day of their cruel and often indefinite detention generates more revenue for the company.

In The Infiltrators—which won the NEXT Innovator Award at Sundance last weekend—directing-couple Alex Rivera (Sleep Dealer) and Cristina Ibarra (Las Marthas) tell the astonishing story of the National Immigrant Youth Alliance (NIYA), a group of teenage undocumented activists who infiltrated the Broward Center in 2012 to prevent deportations and release detainees. Rivera and Ibarra started filming with the NIYA soon after one of its leading members, Marco Saavedra, let himself get caught and locked up at Broward with the aim of freeing an Argentinian detainee named Claudio Rojas. In the days that followed, the directors closely documented the activists on the outside as they coordinated with Saavedra—and later, with Viridiana Martinez, who infiltrated the women’s section—to smuggle documents in and out of the center and pressure local Congressmen to stop specific deportations. Their lack of access to the main site of action—i.e., the detention center—forced Rivera and Ibarra to get creative with the format of the film.

“There was no way to tell the story with the footage we had,” says Rivera, as we chat in Park City a few days after The Infiltrators’ warmly-received premiere. Instead, he and Ibarra devised a uniquely hybrid structure for the film, supplementing their documentary footage with stylish re-enactments of the goings-on within the detention center. The film zips back-and-forth between these two, distinct modes: the documented portions are gritty and handheld, while the dramatized scenes are shot with all the thrilling stylistics of a heist film, from clever one-liners to slickly-edited, Oceans Eleven-esque sequences of Saavedra and the other detainees hoodwinking the guards. The split adds an almost fantastical, game-like edge to the film. The detention center and the outside world feel like separate universes traversed by a phone call, like in The Matrix.

“The fiction gives us pleasure and playfulness,” says Rivera, “ but the doc keeps it grounded in what we all know is an urgent humanitarian crisis. So it lets you have the cake and eat it, too.”

The documentary footage consists mostly of people talking on the phone in restaurants and living rooms, but it’s enlivened by the eloquence and grit of the young activists. One of the high points of the film is when Viridiana prepares to get caught at the entrance to Broward and rehearses her lines with Mohammed “Mo” Abdollahi, the charismatic leader the NIYA. In between giggles, Viridiana attempts different variations of “broken” English, while Mo advises her to look more “pitiful.” They’re both keenly aware of the stereotypes that are foisted upon them and know exactly how to weaponize them to their own advantage.

For Rivera and Ibarra, the chance to tell the story of these activists was also a chance to challenge mainstream media representations of immigrants. “In the right-wing, you see these constant, repetitive images of immigrants as invaders and criminals,” says Ibarra, “and then in liberal circles, you just see representations of suffering, of the bodies in the desert. But coming from immigrant families, we know that’s not the full picture—immigrants are also incredibly savvy, sophisticated, and intelligent political actors.” It’s a bit surreal to see The Infiltrators in 2019, when the conversation around immigration has taken center stage, and to remind oneself that the events depicted took place in 2012, during the Obama administration. It’s both an antidote to cultural amnesia—a reminder that oppressive immigration policies have extended beyond presidencies—and a call to action. Rivera and Ibarra end the film on a somber, open-ended note, emphasizing that Claudio Rojas, who was ultimately released with the help of the NIYA, is still caught up in hearings and trials. “I mean, it’s impossible to have any kind of closure,” says Ibarra. “so we intended to suspend the audience in the present and say that the battle they saw in the film ended, but the war continues.” Their riling, rousing film is an active contribution to that effort, a reminder that resistance can be as powerful as repression, even when you have everything to lose.

Devika Girish is a freelance film critic. She grew up in India and currently lives in Los Angeles.