Sundance 2022 Dispatch #3: Documentaries

This article appeared in the February 1, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy (Clarence “Coodie” Simmons and Chike Ozah, 2022)

In recent weeks, Sundance’s documentary programmers have found themselves embroiled in curatorial controversy. The subject of intense debate and speculation is U.S. Documentary Competition selection Jihad Rehab, which follows a group of former Guantanamo Bay detainees, all Yemeni men, as they participate in a yearlong Saudi government program that seeks to deradicalize them. Before anyone had an opportunity to lay eyes on Jihad Rehab, director Meg Smaker raised eyebrows with her film’s flippant title (evoking an Islamophobic TLC reality program) and its anonymous Saudi producer (raising questions about access, funding, and motives).

Jihad Rehab focuses on the Mohammed Bin Naif Counseling and Care Center, which the film bills as the “world’s first terrorist rehabilitation center.” Extensive opening text traces the history of this program back to the 1980s, when both the CIA and the Saudi militant Osama bin Laden channeled resources to the Afghan mujahideen during their war with the Soviet Union. Jihad Rehab’s early moments are its most baldly objectionable, indulging in gawdy prison-film aesthetics and sensationalist framing devices. A symphonic score goes into overdrive as the film presents a montage of suicide bombings. A detainee smiles after he says he didn’t understand why 9/11 was such a big deal (“I mean, a plane hit a building… just build another one!”) and cues a horror string stab. Smaker introduces each of her three central subjects behind a wall of redacted text. As their reasons for detention are gradually “declassified” (specialized weapons training, member of Al Qaeda, etc.), the film momentarily transforms the men into terrorist trading cards.

Like the U.S. government, the film never substantiates any of these accusations. After watching Jihad Rehab, I Googled one subject whose full name appears in the film and read a prominent human rights organization’s reporting on his case (I’m withholding specific details to not further expose his identity). They write that he has never been accused of an act of violence and has consistently maintained his innocence; the only evidence against him is shaky testimony extracted from a few of his fellow Guantanamo inmates. At the beginning of Jihad Rehab, this same subject maintains his innocence (“No, I didn’t kill anyone, I didn’t do anything”), but Smaker seems unconvinced. Her questioning registers more as interrogation than inquiry. After he says his time in Afghanistan was more like a vacation, she quips, “Like vacation with Al Qaeda?” In a later scene, a rehabilitation center representative tells this subject: “The more you are clear and honest with us, the better the outcome will be.” Thereafter he presents as guilty. Jihad Rehab frames this moment as a breakthrough, granting no space to the possibility that this man is simply performing a role (for the Center or for the camera) so he can survive. Late in the film, when this subject finally receives his freedom, he tells Smaker he’s done with her project because “you eat the mind.”

After its fearmongering opening, the film turns blandly humanist as it constructs a narrative of rehabilitation for its three subjects. We are not offered much to interpret here. The footage from the Mohammed Bin Naif Center is shot in an observational style, but there are no substantial scenes to live inside, no images that speak to the textures of its subjects’ daily lives. The access feels superficial, and the resulting footage is edited like a promo video. In moments, the cuts can verge on the parodic, like when an overenthusiastic instructor tells us the school’s goal is to teach critical thinking skills, and the film pairs his assertion with this epiphanic classroom exchange:

Teacher: “Those who put on a belt and blew themselves up, why did they do that?”

Student: “…Because of emotion?”

Teacher: “Because of emotion!”

Exhausting and infuriating, Jihad Rehab feels like it exercises every egregious aesthetic impulse encouraged by the U.S. documentary industry as it impotently engages with the aftermath of the same country’s human rights abuses. This film is woefully ill-equipped to handle the ethical stakes of its subject, its eyes trained not on reality but, condescendingly, on an imagined audience of Americans with short attention spans and delicate sensibilities.

To the film’s credit, it does give ample space to its subjects’ horrific experiences at Guantanamo, though Smaker’s decision to pair their traumatic testimony with somber-whimsical animation is unfortunate. And in its final stretch, as Mohammed bin Salman rises to power, challenging the film’s access and the lives of its Yemeni subjects, Smaker suddenly pulls an about-face on the Saudi government. What to make of these final minutes, I’m not sure. Is this evidence that a previously naive, opportunistic director is turning into a more nuanced one? I suppose we’ll find out in her next project. According to IndieWire, “she wants to shoot a film about a dwarf who’s a warlord in Afghanistan.”

In another competition entry, I Didn’t See You There, filmmaker Reid Davenport reflects on the legacy of the circus freak show, a spectacle built around “being looked at, but not seen.” “Freak shows used to display certain people—brown, queer, disabled—as ‘human oddities,’” Davenport explains, citing Calvin Phillips (“the famous American dwarf child”) and Chang and Eng Bunker (“Siamese Double Boys”) as examples. Davenport, who has cerebral palsy and is visibly disabled, wonders if documentary is an extension of the freak show, with contemporary audiences existing as an echo of yesterday’s circus attendees, “insistent on their noble desire to open their eyes to a new perspective.”

In response to these nagging feelings, Davenport decides to step behind the camera and create his own audiovisual language, shooting a diaristic portrait of his life in Oakland. This isn’t Davenport’s first film, but thanks to a new camera rig, it is his first time working as director of photography. The result is a sublime, playful film that thrills to the possibilities of image composition. Rushing over bright, multicolored streets in his wheelchair, Davenport transforms them into dazzling pinwheels; pointing his camera up at a flytrap, he creates a strange and towering monument.

Davenport’s evocation of the freak show is provoked in part by a gigantic circus tent that pops up in his neighborhood, regularly invading his frame. It’s an unwelcome imposition, not unlike the pedestrians who blithely block his wheelchair’s path. In these moments, Davenport demonstrates a deft knack for locating droll humor or improbable beauty. At one point, a bus worker insists Davenport turn his wheelchair around. As a confused Davenport follows this command, his camera happens into one of the film’s most stunning shots: an array of the intrigued, disinterested, and weary faces of his fellow bus passengers, all navigating public eye contact in their own distinctive ways. Deservedly, I Didn’t See You There was awarded the Best Director prize in the U.S. Documentary Competition.

Another nonfiction highlight was Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes – A Lengthening, the sole documentary in the festival’s Spotlight section. As its title bluntly promises, Stigter’s film is an extended, essayistic riff on a three-minute travelogue film. Shot by amateur filmmaker David Kurtz in 1938 and unearthed by his grandson Glenn Kurtz in 2009, the 16mm clip is a charming transmission from the streets of Nasielsk, then a small, predominantly Jewish village around 30 miles north of Warsaw. Nearly every smiling person in this footage was later murdered in the Holocaust. Three Minutes steeps in the bittersweet images of the original clip as it scrutinizes them for contextual clues. In voiceover, Glenn Kurtz explains how contemporary technology allowed him to identify faces and then track down anecdotes from the town. There’s nothing shocking about what he uncovers, but each lovingly researched tangent, exploring everything from the hierarchies implied by young boys’ caps to the story of the town’s famous button factory, deepens our connection to the images.

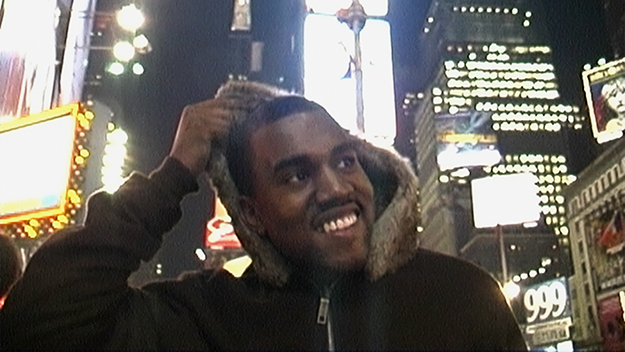

Preoccupations with the vitality and limitations of the archive surfaced again and again in Sundance’s documentary premieres, ranging from Sam Green’s New Frontiers performance 32 Sounds to Sierra Pettengill’s NEXT selection Riotsville, U.S.A. Clarence “Coodie” Simmons and Chike Ozah’s jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy is technically a longitudinal documentary, but given society’s widespread familiarity with its much-mediated subject (the origin story of the superstar Kanye West) and our collective distance from it (two decades), the film can’t help but play as a miraculous archival documentary. The edit frequently finds humor in its temporal remove: at one point, we watch a Roc-A-Fella employee say, “Oh, you get a Blackberry? I heard that’s the thing to have now because you get full emails on it.”

Sundance screened the first film in the jeen-yuhs trilogy, Act 1: Vision, in its Premieres section (the other two sections will premiere on Netflix in late February). Over an enthralling hour and half, the film documents West’s desperate attempts in the early 2000s to be signed by Roc-A-Fella Records, a label that then valued him for his formidable producing skills (he created several key beats on Jay-Z’s The Blueprint) but expressed little interest in his potential as a solo artist. While the industry didn’t immediately believe in Kanye, co-director Coodie certainly did. A former stand-up comedian turned community access TV host, Coodie met a teenage Kanye while filming a segment of his show. Obsessed with the young artist, in 2002 he abandoned his life in Chicago to head east and make a Hoop Dreams–inspired project about West’s search for a record deal. Acting as West’s de facto videographer, he shot extensive, raw, observational footage of the musician’s journey.

Coodie extensively annotates this footage. No matter how long they appear for, how much they say, or how “important” they are, every single person, from unsung Chicago artists to record label assistants, receives an on-screen title. It’s an unusual and endearing decision. Coodie offers insightful context in his earnest voiceover, but by and large, he allows his gorgeous, intimate footage to speak for itself.

The key scene of jeen-yuhs, or at least the one that made me bawl, takes place back in New York City at The Hit Factory. Still unsigned and unrespected as an emcee, West is sitting on an extraordinary beat, “Jesus Walks,” and is courting former collaborator Scarface, hoping the Houston legend will guest on the chorus. Scarface walks into the studio, listens to “Jesus Walks,” and responds enthusiastically, “that’s hard.” An overeager West seeks confirmation that Scarface will appear on the chorus, but Face’s mind is elsewhere, and he asks West to play another beat. West cues up “Family Business.” Scarface perks up and says six of the most meaningful words West could ever hear: “I want to hear you rhyme.” Startled, West delivers the first verse and is met with emphatic approval from Scarface, “That was the shit, man.” West beams before the ultimate humbling moment: Scarface chiding him for leaving his dirty retainers on the table.

Chris Boeckmann is a story consultant, writer, and programmer from Missouri. He is working on Subject, a research project looking at the long-term repercussions nonfiction films have on their participants.