Singing Samurai and Dancing Salarymen

Matsuko

What makes a movie musical? An enlightening and entertaining 10-film retrospective at Japan Society aims to answer that question in the broadest possible way—a necessity given that the genre has been underrepresented in accounts of Japan’s long cinema history. Through this series, programmed by film scholar Michael Raine, American audiences may be surprised to discover that the roots of the movie musical in Japan are nearly as intertwined with the rest of the country’s film history as they are in the U.S.

As in other Asian film industries, musicals in Japan were often offshoots from the careers of popular recording artists. Call it the Elvis Presley or Judy Garland–style production, engineered mainly as a way of selling more records. One of the earliest, and a longstanding classic that has seen frequent revival both at home and overseas, is Singing Lovebirds (39), directed by chanbara and jidai-geki genius Masahiro Makino. It’s usually tagged as a “samurai musical,” and while that reductive characterization isn’t inaccurate—swordplay-film superstar Chiezo Kataoka is featured, and he does indeed sing—the movie is much more than that. A costumed operetta not far from the works of Gilbert and Sullivan (had they been on one of Commodore Perry’s “black ships” in the mid-1800s), Singing Lovebirds matches up contemporary jazz singers (Dick Mine and Tomiko Hattori) with classical actors (including Takashi Shimura, later one of Akira Kurosawa’s regular collaborators) in a lighthearted story about courtship and matchmaking that, in grand musical style, exalts pure love far above money or status. Rich with songs and recitatives, it’s been rightfully hailed as a cinema landmark, and is the most characteristically “Japanese” of the series, despite its predominantly Western-style musical score.

Much more Western in look as well as sound, but still more a vehicle to sell records than a film proper, is Toshio Sugie’s 1955 popular song-style musical So Young, So Bright, the first entry in a long-running subgenre of “three girls” films. These outings would team up a trio of young singing stars to please teenage fans flocking to the cinemas in the post-Occupation era. A longtime contract director for Toho, Sugie was a reliable artisan who contributed entries to nearly every popular, modern-set series produced by the studio. So Young, So Bright is no exception, a colorful, fluffy, formulaic musical drama starring three recording superstars of the era: Chiemi Eri, Izumi Yukimura, and the undisputed Queen of Japanese Pop Music, Hibari Misora, sometimes referred to as “the Japanese Judy Garland.” Misora and Eri play high school friends who undertake a mission to rescue an apprentice geisha (Yukimura) from a creepy patron, and the singers each get to shine in individual performances of popular songs, presented outside the regular narrative but as entertaining as anything created by Busby Berkeley (if a bit smaller in scale). Filled to the brim with hand-wringing melodrama and nothing that might upset the 1950s status quo, the film is nevertheless worth seeing for a taste of the bright perkiness that made Hibari so popular (her funeral in 1989 attracted nearly 50,000 mourners), particularly since her films have almost never been exported or distributed internationally.

Twilight Saloon

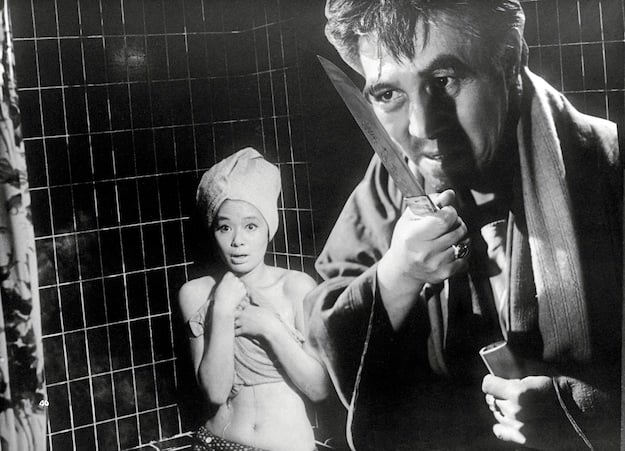

Released the same year but remarkably different in both tone and execution is Twilight Saloon (55), produced by splinter studio Shintoho. This black-and-white musical drama was directed by Tomu Uchida, a master filmmaker whose genius still goes underrecognized in the West. Popular and successful in the 1920s and ’30s, Uchida went to work for the Manchurian Film Association in 1945 and wound up staying in China for eight years after the war, assisting the development of the recovering film industry there, but also disillusioned by Japan’s imperial atrocities. Deeply reflective of this sober attitude, Twilight Saloon is an overlooked classic, notable not only for its attempt to reconcile national pride with the collective shame of the war but also for its remarkable technical achievements. Its action takes place over the course of one night in an izakaya drinking establishment, with the camera ranging all over a massive, two-level set to capture the comings and goings of over a dozen main characters. Featuring musical performances on the saloon’s main stage and impromptu songs from its patrons—as well as a constant backdrop of natural harmonies from the sounds of the environment—the movie anticipates Robert Altman’s best ensemble works in its overlapping dialogue, busy mise en scène, and naturalistic performances. But the tone also calls to mind the postwar uncertainty of The Best Years of Our Lives and the blackly humorous melancholy of Casablanca. (One wonderful sequence stages Bizet’s “Toreador Song” from Carmen in a way that channels the “La Marseillaise” scene in Casablanca to far different effect.) A remarkable achievement in social realism, leavened with light humor and music, Twilight Saloon leaves a viewer with the feeling of having spent a night drinking with these characters; one of the rarer titles in the Japan Society series, it’s worth seeing at all costs.

A notable exception to the song-style musical came in the form of the “Nikkatsu Action” films of the ’50s and ’60s. The stars in these films usually had musical careers, but the musical careers were created in order to promote the movies rather than the reverse. Such was the case for the biggest male star of the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, Yujiro Ishihara, who started at Nikkatsu in 1956 with a pair of wayward-youth dramas and only a year later was the most popular actor at the studio. The Stormy Man (57; also known as The Man Who Caused a Storm) was a big-budget, prestige production for the company, starring Ishihara as a bad boy hoodlum with mother issues who becomes a popular jazz drummer but can’t stay out of trouble. Set in the world of smoky jazz clubs and cutthroat competition, it’s not a traditional musical but it features an acclaimed centerpiece in a drum showdown between newbie Ishihara, his hand wounded in a fight, and the reigning drum king, who’s backed by powerful mobster friends. Crime, corruption, tabloid journalism, and love triangles typify Nikkatsu’s genre entries, and all of them figure in this classic example, which crackles with Ishihara’s raw, animalistic power. Director Umetsugu Inoue was one of Nikkatsu’s most popular filmmakers, responsible for their biggest and glossiest productions; he was later loaned to Shaw Brothers in Hong Kong, where he remade The Stormy Man as King Drummer (67). Nikkatsu did their own remake, in 1966, with Tokyo Drifter star and Ishihara protégé Tetsuya Watari in the lead role.

You Can Succeed, Too

You Can Succeed, Too

One of the most popular comedians of the era, Frankie Sakai, makes a cameo in Stormy Man as a jailbird who claims he’s a better drummer than Ishihara (a joke because Sakai had been a popular jazz drummer during the Occupation years). Chubby and round-faced, he’s the lead in the “Japan Sings” film that comes closest to a Hollywood-style musical: 1964’s Toho production You Can Succeed, Too, a triumphantly entertaining, satirical look inside a Japanese corporation and its attempt to succeed in the international tourism industry. Sakai plays a corporate underling striving to get ahead, and comes off as a self-mocking combination of Lou Costello and Jerry Lewis. Izumi Yukimura appears again, looking like a Japanese Audrey Hepburn as the know-it-all daughter of the company president, recently returned from America with dozens of recommendations about how to make the company better, and future Bond girl Emi Wada has a supporting role as the company president’s giggly mistress. You Can Succeed, Too equally evokes Vincente Minnelli and Frank Tashlin, and its gigantic set and dancing corporate employees were likely a major influence on Johnnie To’s recent 3-D Office. It’s packed with narrative songs that are fully integrated into the story and the dialogue, with music by prolific composer Toshiro Mayuzumi, who did everything from Profound Desires of the Gods (68) to John Huston’s The Bible (66). With massive dance sequences and a pitch-perfect takedown of both domestic corporate culture and the fetish for praising anything foreign, it’s a surprisingly subversive comedy given the time and place it was made.

Similar aspirations drive the 1962 film Irresponsible Era of Japan, though the results are decidedly less successful. Part of the popular “Crazy Cats” series produced by Toho as vehicles for a group of TV comedians and musicians led by Hajime Hana and Hitoshi Ueki, the film is also set in the world of corporate shenanigans, with Ueki starring as a ne’er-do-well con man who weasels his way into a corporate job where he becomes an overnight success. Very few musical sequences enlighten the satirical comedy, and the Crazy Cats are definitely an acquired taste for foreign audiences.

Oh, Bomb!

A more successful parody can be found in the ingenious, dark satire of Oh, Bomb! (64), directed by Kihachi Okamoto. Kurosawa favorite Yunosuke Ito stars as a sad-sack yakuza boss who’s released from prison only to find that his gang has been turned corporate and taken over by a rival. This formulaic setup—reportedly inspired by a Cornell Woolrich story!—is merely the basis for an unclassifiable and avant-garde deconstruction of the entire crime genre, presented, start to finish, as a musical. Okamoto’s brilliant direction and editing turns every cut and movement into a musical beat, with Masaru Sato’s score encompassing Western songs, Noh recitations, Buddhist chanting, and kabuki shouts. The title refers to two long, astonishing sequences that adapt Hitchcock’s bomb-under-the-table formula for suspense—substituting an explosive pen and a golf ball—and extends it into a masterpiece of physical comedy. Similar in absurdist tone to Okamoto’s Age of Assassins (67), it’s the kind of film which is still ahead of its time.

Okamoto’s boundary-pushing film can also be seen as the progenitor of further experimental musical films featured in the series. Nagisa Oshima’s dense and complex A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs (aka Sing a Song of Sex, 67) stirs dirty drinking songs, Pete Seeger protest tunes, and Japanese workers’ anthems into the story of a group of politically disengaged students who fantasize about rape, culminating in a classroom lecture about the Korean origin of the Japanese people. Even further afield are two more contemporary entries, Takashi Miike’s delightful The Happiness of the Katakuris (01), the musical remake of a Korean black comedy about a family who buy a rural boarding house, only to be forced to go into the corpse-disposal business (Miike’s version adds dancing zombies); and Tetsuya Nakashima’s brilliant and devastating Memories of Matsuko (06), which follows Citizen Kane’s lead, with a young man reconstructing the sad life of his aunt, whose eternal optimism—depicted via elaborate, colorful, fantasy musical sequences—allowed her to endure physical and mental abuse, failed marriages, prison, and eventually homelessness and madness. As with Twilight Saloon, the Japanese musical turns out to be a genre which very often includes sadness and depression, proving that singing and dancing are sometimes the only way to shut out the darkness.

Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film runs through April 23 at Japan Society in New York.

Marc Walkow is a writer and film programmer living in New York. Formerly a director of the New York Asian Film Festival, he has also produced DVDs and Blu-rays for Criterion and Arrow Video.