Interview: Shunji Iwai

Love Letter

Born in 1963, Japanese writer-director Shunji Iwai first drew attention through offbeat television dramas like Ghost Soup. But his breakthrough feature was Love Letter (1995), an international success that received a U.S. release under the title When I Close My Eyes. Love Letter has many of the hallmarks of Iwai’s style: sweeping camera movements tied to formal framing; a score mixing rhapsodic pop with classical themes; a storyline that breaks into unexpected tangents; and jarring shifts in tone from comedy to cruelty and hopelessness. Shot mostly in a snowbound Hokkaidō, it was one of six theatrical collaborations between Iwai and cinematographer Noboru Shinoda.

Iwai is revered in Japan for such genre-bending, multimedia epics, and at the 15th New York Asian Film Festival at FSLC, the writer-director received a Lifetime Achievement Award. In an interview with FILM COMMENT, he discussed his career, including his latest film, A Bride for Rip Van Winkle, which screened in NYAFF and last week at Fantasia Fest.

For Iwai, his movies revolve around characters who are somehow cut off from society and relationships. As their stories unfold, as they experience pain and loss, the world opens to them.

“I loved that sense as a child that there is only the one small area around you,” he said. “I remember a big street, actually not that big but it felt like it as a child, a street I couldn’t cross because it was so dangerous. That place across the street is another world. When I write, I always remember that sense, that imaginary distance.”

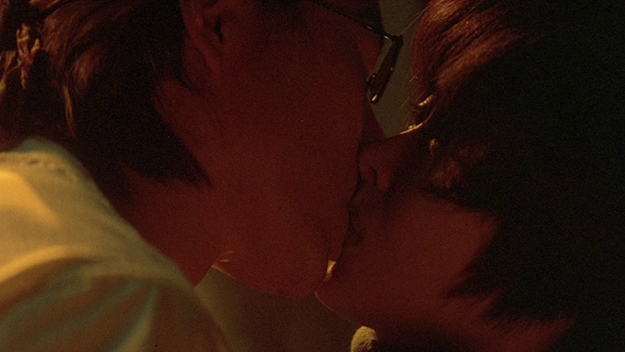

Love Letter

In Love Letter, Iwai cast pop singer Miho Nakayama in a dual role as Hiroko, a grieving fiancée, and a woman (also named Hiroko) who was her boyfriend’s lover.

“In my stories, the most important thing is we don’t know each other,” he said. “It’s hard to understand even your partner. Sometimes people think of their partner, ‘It’s mine, she’s mine, he’s mine. Everything. I’m him, I’m her.’ That’s what Hiroko thought when she loses her partner, and then she finds another woman’s letters, and she gradually sees memories she never knew. It’s a way of seeing her fiancé again.”

Lengthy flashbacks exploring a passionate childhood love affair helped endear Love Letter to young viewers across Asia. Iwai followed it with the unclassifiable Swallowtail (1996). Part musical, part sci-fi, part documentary, the movie pulls together prostitutes, punks, gangsters, and illegal aliens called “Yentowns” in a grimy near-future.

Swallowtail was a huge undertaking that brimmed with barely contained ideas. Iwai mixed languages, shot scenes guerrilla-style on city streets, concocted fake music videos and MTV-style interviews, and layered words over images, achieving an exuberant, jump-cut style that veered from extended nightclub jams to police interrogations, from shoot-outs to urchins falling in love. One of the soundtrack’s songs rose to number one on the charts; Iwai had given a prominent role to pop singer Chara (who also appeared in his TV film Picnic). Her sputtering version of “My Way,” backed by polyglot rockers, became a pop culture moment.

All About Lily Chou-Chou

All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001) was an even more successful attempt to blend film, the burgeoning Internet, and pop culture. Based loosely around a fictional pop star named Lily Chou-Chou, the story follows school friends as they are influenced and possibly corrupted by the stars they idolize. Iwai wrote an Internet novel based on the characters before starting production, and incorporated plot elements from fan postings into his script.

Although critics at the time noted how accurately Iwai depicted the teens, they were dismayed by plot twists that delved into bullying and rape in the small-town setting.

“All these entertainment companies—music and movies—send their content to everyone, not just city kids but also small-town kids. I thought that might break the balance in their life.” Pointing to a production still from All About Lily Chou-Chou that showed a teen in a white shirt standing alone in an immense field of green, Iwai continued: “For a kid living in a small town, 70 to 80 percent of his life looks like this. But he’s getting all this information telling him he’s supposed to be hard-core, urban.”

After writing and directing a comedy, Hana & Alice (2004), Iwai had trouble financing his next feature. “I write a lot of scripts, but producers in Japan only pick up something like one in three scripts,” he explained. “My last one, The Case of Hana & Alice, I actually wrote over ten years ago.”

Hana & Alice

Iwai instead branched out, producing Bandage (2010) for his frequent composer Takeshi Kobayashi and features by Eriko Kitagawa; directing a documentary on Kon Ichikawa; shooting music videos; composing pop songs and soundtracks; working in animation; and writing and directing his English-language debut, Vampire (2011).

Iwai’s latest project, A Bride for Rip Van Winkle, started out as a novel. The story follows Nanami (Haru Kuroki), a shy, diffident, only child who struggles as a part-time teacher. She marries Tetsuya (Go Jibiki), another teacher, but an encounter with possible con artist Amuro (Go Ayano) throws her life into a tailspin.

A Bride for Rip Van Winkle exists in several versions, including a two-hour edit for international markets, Iwai’s own three-hour theatrical edit, and a four-and-a-half-hour version for television. Eleven Arts will be releasing the three-hour version in the U.S. this fall.

“I wrote the original novel. Then when I wrote the script, I took it apart, every shot. It’s really tough to budget a movie in Japan, but we can get more money if we exploit all the platforms. That’s the most challenging part of making a movie now,” Iwai said.

A Bride for Rip Van Winkle

Iwai prefers the three-hour version, but says that it is missing material. “It’s not perfect. Even the TV version, the longest, isn’t perfect because it doesn’t have a very, very important scene in the climax. You can only see that in the three-hour version.”

A Bride for Rip Van Winkle mirrors Iwai’s past work but with new sympathy for his characters. Nanami has been living in an illusion of stable middle-class life, one that cracks before her eyes. “Why me?” is her standard response — when her parents divorce, when she is fired from a job, when her mother-in-law turns against her, when she wanders lost in an industrial park. Iwai fixes on each downward turn in her life, no matter how cruel. At one point, Nanami writes in her blog that Internet dating “is too easy, like shopping online”—before impulsively agreeing to wed a blind date.

“I think she always has some responsibility for what happens to her,” Iwai said. “But I think her case could happen to anyone. Sometimes we tell a small lie, and we don’t care. But then what happens?”

Earlier in his career, Iwai might have fashioned a harsher fate for Nanami. But thanks to Amuro, she befriends Mashiro Satonaka (pop star Cocco), a wealthy actress. Falling ill, Mashiro wants to give Nanami life advice. Iwai stages the scene in a single, six-minute shot, Chigi Kanbe’s camera starting wide and gradually moving in tightly on Cocco and Haru Kuroki. The world is full of happiness, the dying actress tells her, adding that she would give all her money to spread happiness.

A Bride for Rip Van Winkle

“I wrote that character first, but I couldn’t find the right person,” Iwai explained. “I happened to go to the theater, and Cocco was there. After she accepted the part, I wrote that scene for her. I tried to think of what she, Cocco, would like to talk about at the end of her life. Her speech is very unique—some of her fans get into her too much because her speech is so mesmerizing. I just tried to mimic her.”

On screen the scene is a suspended moment so gentle and subtle, you may not realize how rich and complicated Iwai’s technique is. And in A Bride for Rip Van Winkle, he’s used those skills to focus on Japan’s cast-offs with a newfound compassion.

Thanks to Marie Iida for help translating.

Daniel Eagan is a critic and film historian living in New York City. He is currently working on the third volume of America’s Film Legacy, a survey of the National Film Registry.