Deep Focus: Rogue One: A Star Wars Story

“Rebellions are built on hope,” says Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. So are movie franchises. The team behind the re-launch of the Star Wars saga has made it their main goal to keep hope alive among their multitudinous viewership. Last year their gift to fans was to craft a mashup of Star Wars: A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. This year their early Christmas present is the first “stand-alone” Star Wars movie, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. This prequel to A New Hope is vastly different from George Lucas’s own prequels: it tries to meld Lucas’s idiosyncratic, eye-popping vision of a republic degenerating into an empire with a rock-’em, sock-’em combat film. A friend of mine who is a Star Wars fanatic has said that these films will play to separate audiences. According to his theory, Rogue One will put off anyone who loved The Force Awakens, and vice versa. Actually, although The Force Awakens has the edge in entertainment value, the two movies are roughly similar.

They’re both dubious feats of calculation, geared to deliver pieces of nostalgia to the Star Wars faithful (such as the digital incarnation of a New Hope figure that appears in Rogue One) and to introduce fresh audiences to the saga with bite-size pieces of mythology. The formula may work again commercially and even as “fan service” on a gargantuan scale—the response to the appearances of three original-trilogy characters is tumultuous. But the ongoing hope for this franchise is that it keeps finding a new director every time out. J.J. Abrams made The Force Awakens into an Abrams movie, juggling a cavalcade of pop personalities and scads of hit-or-miss action. Gareth Edwards has made Rogue One into an Edwards movie like Godzilla (14), beginning with traumatic death and separation, then slogging through a muddled mid-section to a spectacle-filled (if not entirely spectacular) finale. I’m hopeful about the next Star Wars film mostly because Rian Johnson (Brick, Looper) is directing it.

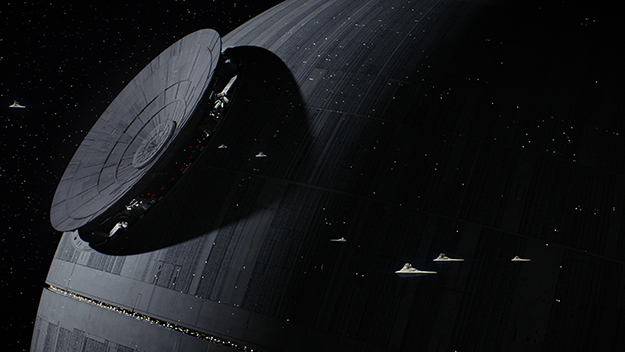

Rogue One starts beautifully, with a stirring, scary vignette of a family torn apart against the backdrop of imperial manipulation. All the emotion the scene needs plays across the face of the superb Mads Mikkelsen as Galen Erso, a scientist turned farmer who strives to keep his wife Lyra (Valene Kane) and his daughter Jyn (Dolly and Beau Gadsdon) out of the clutches of Orson Krennic (Ben Mendelsohn), a former friend and colleague who is racing up the Empire’s greasy pole. (The movie’s few subtle jokes are aimed at middle management.) Krennic has tracked Galen across the galaxy to his remote and modest farm in order to dragoon him into working on a super-weapon that series followers will recognize as the Death Star. Mikkelsen seizes on his sole chance to act in the movie, and pulls off a splendid display of desperation and bad lying, while Mendelsohn seems at ease for the only time in the picture, skillfully conveying that Orson loves putting his personal knowledge to sadistic use. (In this scene, Mendelsohn does a Christoph Waltz number better than Waltz does these days.)

This opening boasts the best and wittiest interchange: when Galen says that Orson has confused establishing peace and security with “terror,” Orson responds, wryly, “You have to start somewhere.” In his brief career, Edwards has done his most promising direction on a small scale (his modest 2010 debut, Monsters), and that’s true in this scene. He works the feeling of a coming-of-age fable into the sight of the white-clad Orson marching through the scrublands with black-armored “Death Troopers” and the young Jyn scrambling into a tunnel hidden within a cave, where she cowers and prays until the portal opens to reveal the face of Saw Gerrera (Forest Whitaker), the man her father chose to rescue her. The movie peaks with that first sight of Whitaker, who suggests, in a second or two, the kind of pleasurably flamboyant performance he hasn’t delivered since The Last King of Scotland.

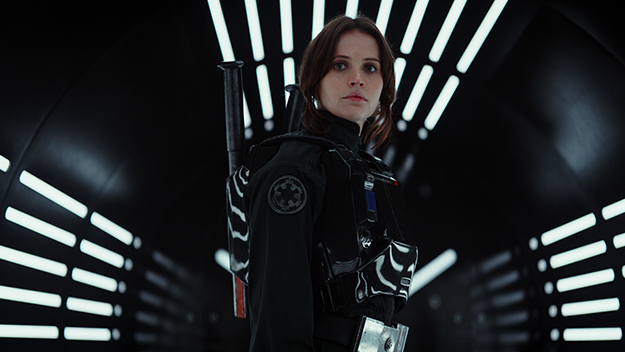

Rogue One begins wonderfully because Edwards commits no unforced errors, his technique is expressive, and he sketches the thumbnail versions of the characters masterfully well. But as soon as we catch up to the grownup Jyn (Felicity Jones), the film’s vitality fades into the murky air. The story ricochets haphazardly as Edwards hurtles us from one planet or moon to the next, the printed titles on the screen displaying their names, functions, and political affiliations as impersonally as POWs offering their names, ranks, and serial numbers.

What we’d call “the rising action”—if it actually did rise—depicts the formation of a Rebel vanguard unit around the peevish twentysomething Jyn and a moody Rebel captain, Cassian Andor (Diego Luna). Saw had cut Jyn loose at age 15; since Orson had coerced her father into working for the Empire, Saw worried for Jyn’s safety among Rebels who’d view Galen as an enemy. (The question of whether Galen did, in fact, break bad, gets answered pretty quickly.) Since then, Jyn has survived by her wits on the street and in jail. Cassian, for his part, has been a cutthroat assassin in the service of the Rebels. Along with Whitaker’s Guerara, a militant who has alienated Rebel peers and possible Rebel sympathizers, these characters are meant to carry the weight of the story’s moral complexity.

Still, Cassian’s cold-blooded espionage, Jyn’s criminal past, and even Saw’s civilian-threatening bouts of terrorism pale before the depredations of the Empire, whose Storm Troopers and agents move like the Gestapo through occupied territories. At her height of petulance, Jyn proclaims that she never had the luxury to be “political,” and at his pit of self-loathing, Cassian confesses that he couldn’t live with his gore-streaked past if it weren’t for his belief in the Rebel cause. But their existential complaints register as mere rhetorical flourishes when weighed against the Empire’s creation of a weapon dubbed a “planet-killer.” I guess we’re meant to assume that Saw has been horrifically awful because he’s as patched up with armor and as reliant on a breathing machine as Mad Max: Fury Road’s Immortan Joe.

Since the old and new Star Wars series rest on our recognition of the Empire as a vile totalitarian regime, it’s difficult to hatch a suspense-filled plot that depends on good guys coming to their senses about just how bad the imperial forces really are. The “Rogue One” of the title refers to our heroes’ stolen imperial cargo ship. It also suggests the Rebellion 101 storyline: a handful of warriors huddle together and go rogue as they attempt to eliminate the threat of the Empire’s new super-weapon.

The talented writer-directors who share the main script credit, Chris Weitz (who wrote Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella and directed A Better Life) and Tony Gilroy (who made Michael Clayton) might have conceived of a movie that would fill in the contours of a corrupt empire on the fly, the way George Miller did in the most inventive parts of Fury Road. Edwards has shaped the material as if it were a top-heavy band-of-misfits movie, yet another Dirty Half-Dozen, as Jyn and Cassian rally other cast-off or underappreciated talents on a mission to find her father and learn the secret defect he says he built into the Death Star. (Riz Ahmed, a performing dynamo in Nightcrawler and HBO’s The Night Of, is wasted as an imperial cargo pilot who becomes a reluctant Rebel hero; so is Jiang Wen as an earthy, burly, blaster-toting good guy.) After a devastating test of the weapon that evokes Hiroshima and Nagasaki, too many Rebel leaders are ready to cave in to the Empire. Jyn warns that backing away from a foe so evil and powerful means ushering in an eternity of submission. You could say she’s opposed to “normalizing” relations with the fascist Empire. Any attempt at parable stops there.

The movie tries to earn its battle-film bona fides by setting the ultimate clash in a tropical setting that evokes the South Pacific circa World War II. Edwards does generate a real sci-fi frisson when he depicts Imperial Walkers, over 20 meters high, striding across sandy shores. Ace cinematographer Greig Fraser (Zero Dark Thirty, Lion) fails to find his footing there. He can’t merge the Star Wars paraphernalia into a more rough-and-ready style (to be fair, the climax does boast some mind-blowing blends of lighting and special effects). Stalwart composer Michael Giacchino does better at updating rousing or menacing Star Wars motifs with novel, moodier themes.

Though Diego Luna is intriguing casting for Cassian because of his diminutive and elusive presence, he lacks the emotional heft of a reluctant hero. Felicity Jones, who’s been strong and moving for actors’ directors like Stephen Frears (Cheri), Julie Taymor (The Tempest), and Ralph Fiennes (The Invisible Woman), is disappointing in Edwards’s care as Jyn. She puts as much oomph as she can into batting away or blasting Storm Troopers by the dozens (they fall as easily as the Indians did in run-of-the-mill old Westerns), but Edwards has given her nothing distinctive to play during all her derring-do, the way Abrams did Daisy Ridley in The Force Awakens, when she seemed to be grabbing her destiny with her own two hands. Jones can’t save hollow speeches that are meant to be inspirational. Her sermon to the men about taking “the next chance” until they run out relies on mere repetition and falls embarrassingly flat.

As in any Star Wars film, the supporting critters often steal our attention during the gaudiest lightshows. I was particularly fond of Admiral Raddus, designed as an alien bullfrog version of Winston S. Churchill. Played in a motion-capture suit by Paul Kasey and given voice by Stephen Stanton, he’s the only leader who manages to be primal and rousing. It’s telling that the other two characters connecting to every part of the audience either walk through the tumult or adopt an ironic posture. Donnie Yee does the former, turning a blind warrior monk named Chirrut Imwe into a sightless daredevil comparable to Zatoichi or, yes, Daredevil. He’s not a Jedi knight, but he turns his belief in the Force into a mantra, and he strides through laser-powered fusillades without qualm or hesitation, as if his faith has given him an invisible shield. I always enjoy watching him, even as he’s marching toward a master power switch that the Empire for some reason positioned to stand in plain sight at the base of a tower. (I don’t think this was an homage to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter.”)

Alan Tudyk, who performs both on the soundtrack and in a motion-capture suit on stilts, imbues the film’s lanky new droid, the ebony K-2SO, with oodles of irony. The source of the film’s one surefire sight gag, he also provides a deadpan running commentary as a reprogrammed imperial security droid who starts out loyal solely to Cassian but develops a grudging affection for Jyn, too. An inveterate and hilarious truth-teller, he delivers exact estimates of the mission’s probable failures; Tudyk insinuates a sardonic sensibility and deadpan valor into his patter. When he says that Jyn surprises him with how unpredictable she is, we almost believe him.

Tudyk’s K-2S0 has in miniature what Edwards’s movie lacks overall: the soul of a new machine.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.