Review: Dream Scenario

This article appeared in the November 22, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

Dream Scenario (Kristoffer Borgli, 2023)

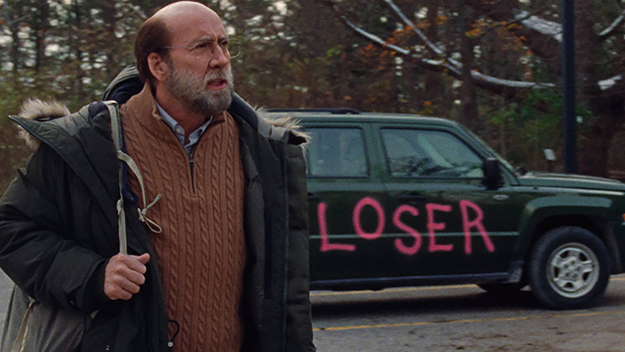

Fresh off of his sophomore feature Sick of Myself (2022)—a delightfully corrosive satire about a narcissistic couple, one of whom acquires outlawed Russian medication to feign disability—Norwegian filmmaker Kristoffer Borgli returns to his familiar themes of notoriety and public delusion with Dream Scenario (2023). Hapless biology professor Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage) is introduced to us as a man begging for academic recognition from a former peer to no avail. He’s characterized by this flailing desperation in every aspect of his life: his students are perpetually unmoved by his lectures on adaptive reasoning; he’s unable to cough up a convincing enough rationale for taking his wife Janet’s (Julianne Nicholson) last name; his two daughters are mortified by his presence, even at the dinner table; and he has no friends. We are acquainted, slowly, with the outline of an invisible man.

Paul’s social temperature begins to rise after a few friends and acquaintances remark that they have all dreamt of him, including an ex-girlfriend who posts about her dream online, resulting in an overwhelming number of similar anecdotes emerging from across the globe. In these dreams, it seems that Paul is comically apathetic, standing watch as the dreamer undergoes some frightening fate but rarely acting; he does not speak and emotes little, stumbling into the scene like a tourist, unfazed by any surrounding action. It’s an amusing twist on the “This Man” phenomenon: in 2008, an Italian sociologist sketched an unidentified, bushy-browed figure who allegedly had appeared in thousands of people’s dreams, though this was eventually revealed to be a hoax. In Dream Scenario, the collective hallucination is all too real, and overnight, Paul is hypervisible and basking in newfound celebrity—news junkets, photos with “fans,” the sudden potential for career advancement. Janet cautions Paul to maintain their privacy as they attempt to feel out this bizarre, unprecedented situation. He does not comply until an unstable, knife-wielding intruder breaks into their home, insisting on killing the mysterious man from his dreams.

And so begins a sudden shift in perception: Paul inexplicably becomes the antagonist of everyone’s nightmares, committing in them acts of torture, sexual assault, and sadism. He switches from bystander to aggressor—from jovial, perplexing social-media sensation to pariah, no longer welcome in professional and personal spaces. Cage’s meme-sanctioned virality has kept the actor in the public consciousness for decades, and his recent slate of reflexive projects are meta-narrativized by Dream Scenario’s arch fantasies of shaping and subverting public personae. But Borgli’s ambitions extend beyond the postmodern workings of celebrity to broad portrayals of “cancel culture”—though his satire is not particularly honed here, often deriding the ballooning public unrest rather than Paul’s misplaced self-conceit. In one scene, his students receive group exposure therapy, at first wincing at a photograph of their wilting professor, then fleeing the scene when he appears in the far corner of the gymnasium to announce his harmlessness. Where Sick of Myself makes its politics—and its contempt for its protagonist—legible, Dream Scenario scarcely feels secure in whom it is mocking.

Regrettably, Dream Scenario then cleaves itself into two distinct parts. If the first offers a compelling look into how our unconscious cultural memory can have tactile consequences, the latter recalls the whirling, tiresome modalities of late-stage Black Mirror, which decry all the vanities of technology from the shallow end of the pool. The film’s last act is dedicated to a parody of latent consumerism, wherein a small device allows one to penetrate others’ dreams at the cost of allowing advertisements and “sponcon” to percolate in their subconscious. The belated injection of sci-fi feels tonally dissonant, and worse, enables a kind of honeyed sympathy for Paul, who pursues an estranged Janet via dream travel. Borgli attempts to reenlist the distinctive flavors of a Charlie Kaufman film: empirical absurdity, chimeric plots, pathetic men doing pathetic things. But where Kaufman’s characters (including the version of himself played by Cage in 2002’s Adaptation) engender feelings of doom and despondency, Borgli’s Paul is a limp conduit for a culture war. It brings me no joy to relay that the film’s ending also seems to rhyme with that of Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale (2022)—both close with an apologetic, maligned man floating into the void, psychically setting things right.

Saffron Maeve is a Toronto-based critic and film programmer.