Review: Crimson Peak

As the documentary Room 237 noted, critics and author Stephen King both panned Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining, which did poorly at the box office on its initial release. Although there was a lingering distaste for Kubrick’s particular brand of high-modernist auteurism (apparent in the vitriol applied to his previous, universally hated film Barry Lyndon), the most common complaint about The Shining was that Kubrick had taken King’s bittersweet family-focused horror and transformed it into a camp free-for-all, a textbook example of “the book’s better.” Thirty-five years on, the critical consensus has flipped, and the film is viewed as a classic of the genre and a testament to the complexity with which Kubrick infused every frame of his films (hence a documentary narrated by conspiracy buffs-slash-formalist film scholars). It’s the sort of ironic twist that comes straight out of fiction: the auteurism that damned The Shining has become its salvation.

Beyond illustrating how attitudes towards authors and authorship change over time, the reception of The Shining is also useful for understanding what is and is not considered acceptable or valuable in a particular genre. Like Kubrick’s film, Guillermo del Toro’s Crimson Peak is an unapologetically lavish, snowy, gothic affair that is completely uninterested in fitting into current genre trends. Whereas many contemporary horror films are deeply invested in postmodernism—knowingly quoting the aesthetics of Eighties horror, employing camp, or being reflexive in other ways (e.g., casting)—del Toro’s film draws primarily upon earlier, literary works, and their film adaptations: Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw and Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. (As Hitchcock did in his adaptation of Rebecca, del Toro uses oversized props to underscore the helplessness of his lead character.) Del Toro calls Crimson Peak a “gothic romance” rather than a straightforward horror film. However, given how amorphous the category of horror is as a formal matter, its designation ultimately comes down how its marketed, which in turn shapes audience expectations—about what a horror film should do well (be scary, gory, etc.) and how it should go about achieving those goals.

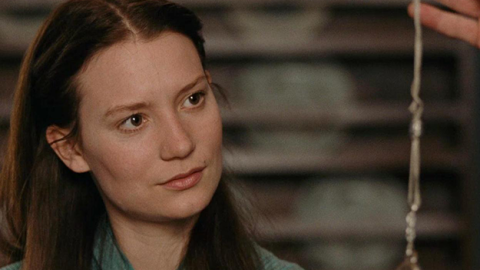

Expectations are a crucial component of any story, and Crimson Peak deploys several Hitchcockian macguffins throughout the film, specifically with regard to whether or not it actually is a horror film. The opening image is beautiful, but also suggests something grisly to follow: a ghostly-pale Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska) stands in an indistinct, snowy landscape—bloodied, breathing heavily, sans coat and holding a knife. “Ghosts are real, this much I know,” she says in breathy voiceover. From here, the film flashes back to reveal how Edith got to this god-forsaken place, which, most unsurprisingly of all, is because of love. The daughter of a builder who worked his way up to the head of an architectural firm in Buffalo, New York, Edith is a thoroughly modern woman who’s ready to shake off the stodgy dust of the Victorian era. An aspiring author (who’s written a novella that isn’t a ghost story but “a story with ghosts in it”), she shuns love and the expectations which high society has for women like her… until she meets Sir Thomas Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston), who successfully whisks her off her feet. (His coup de grâce involves waltzing at a party with Edith while holding a lit candle. Spoiler: it stays lit for the whole dance!) Edith’s father, however, has been wary of Sir Thomas from their first encounter (an investment presentation in which the baronet unsuccessfully pitched a mining machine he’d designed) and, after getting some dirt from a private detective, demands that he and his sister Lucille (a bravura performance by Jessica Chastain) leave town immediately. But the lovers’ separation is short-lived, as Edith’s father gets his head bashed in on a sink the following morning by an anonymous, black-clad assailant at his sports club.

The murder scene is pure giallo, lingering on the gigantic, gaping hole in dad’s skull, and triggers Edith’s turn away from the modernity around her to the dilapidated, old world of the Sharpes’ and their Cumberland estate, Allerdale Hall. Her whirlwind marriage to Thomas occurs during an ellipsis after her father’s funeral, at which another suitor, a rationalist doctor, can only gaze at her sadly from the other side of the grave. The house is truly a character unto itself, with a giant hole in the roof—which makes the house “breathe” through its chimneys—and blood-red clay bubbling up from under the floorboards. (This red clay also colors the snow, giving the estate its suggestive nickname “Crimson Peak.”) The house’s eye-popping extravagance and intricate designs simultaneously conjure feelings of unease and the desire to explore it further—a testament to the benefits of putting money into art direction. The ghosts that haunt Allerdale Hall are equally impressive, and also have a gruesome, giallo aesthetic: bright red (presumably colored by the clay), these skinless, all-female apparitions appear in flowing robes and have joints that pop from rigor mortis, half-Walking Dead zombies, half-Bernini sculptures.

Yet these lady ghosts aren’t the type you’d encounter in Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Dimension or Poltergeist; instead of malicious souls set on revenge, they’re warnings. Specifically, they’re trying to draw Edith’s attention to something that has been hidden in plain sight the entire film: Thomas married her for her money, and he’s been sleeping with his sister. Lucille, who occasionally lets her adoration for Thomas slip (once by jealously throwing a pot of boiling gruel across the kitchen), has been slowly weakening Edith with firethorn berry tea and poisoned porridge, waiting until she’s signed over her fortune to the Sharpe family to bludgeon her to death. While the revelation that Lucille is the driving force behind the murder of their mother (glimpsed in a cartoonishly grim painting) and the series of wealthy, elderly or infirm women Thomas married is a little misogynistic, the prolonged knife fight at the end delivers the siblings’ just deserts—and a deeply satisfying climax that’s as extravagant as Allerton Hall’s wallpaper.

Though Crimson Peak repeatedly begs comparison to novels—be it through Edith’s writing, her voiceover narration that bookends the film, or the presenting of the film’s title on an embroidered book—the act of seeing and perception is ultimately what drives the film. Early on, while Edith visits her lovelorn doctor, he shows her slides of spirit photography he’s purchased. Although we know that these images of another world are faked, the pair sit in awe, chewing over the science of photography and death. “Perhaps we only see things when we need to,” Edith wonders. In Crimson Peak, del Toro shows us everything about the film’s underlying psychological drama both literally (with Lucille’s habitually creepy behavior, by virtue of the fact that Thomas never spends a whole night with Edith) and metaphorically (the blood money that supports Allerton Hall’s continued existence represented by the red, oozing clay that’s beneath it).

If you’re a keen enough viewer, there are no twists—or, at least, the incestuous, murderous couple at the film’s heart won’t really come as a surprise to you. While this may sound slightly anti-climactic, the experience is nonetheless exciting and shocking. In a time when convolution and cheap revelations and reversals clog up the gears of films on this economic scale, not being tricked is the greatest, most rewarding surprise of all.