Rep Diary: Rocco and His Brothers

They called him the Red Duke, and for good reason.

By birth, Luchino Visconti was a nobleman, a descendant of Charlemagne and the family that ruled Milan for centuries. As such, he favored silk shirts, Parisian ties, handmade shoes, and the scent of Hammam Bouquet. But Visconti was also homosexual and a Communist—simultaneously aristocrat and outlier, a beneficiary of tradition and a believer in radical change.

If, as F. Scott Fitzgerald said, the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in your mind at the same time, then Visconti went Fitzgerald one better: he lived a life that depended on an established social order, he believed in the necessity of disrupting that order, and then he rounded back to a deeply poetic appreciation of what was bound to be lost in the transition.

Visconti’s 1960 epic Rocco and His Brothers has had a stealthy but perceptible influence in the 55 years since its release, most prominently in the thematics of Martin Scorsese movies such as Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Casino, and The Departed, all of which involve cohesive units gradually destabilized by forces both within and without.

The 4K restoration of the movie showing at Film Forum before it rolls out across the country should serve as a trenchant reminder that its creator was more than the sum of his contradictory parts: he was also an artistic titan. Among the slew of great Italian directors of the postwar era—De Sica, Fellini, Antonioni, Rossellini—it is Visconti whose posthumous reputation has seemed the most imperiled, perhaps because of his refusal to type himself.

Visconti first gained notice with Ossessione (42) a bootleg version of The Postman Always Rings Twice. He continued along a neorealist path with La Terra Trema (48) and Bellissima (51), but when his career as an opera director took off, a corresponding pomp began infiltrating his movies, as with 1954’s Senso. Rocco and His Brothers constitutes Visconti’s last tussle with neorealism. In its expansiveness and novelistic focus on character and environment at a time of national transition, it looks forward to his 1963 masterpiece The Leopard, but played for passionate intensity instead of a luxurious passivity.

Rocco and His Brothers was a critical and financial success, but it was swept away by the tidal wave of La Dolce Vita, which came out the same year. Fellini’s smash hit must have galled Visconti mightily—the two men disliked each other.

The story is basic: the Parondi family—a mother and five sons—arrive in Milan from a small town in the south. Like all migrants, they are in search of opportunity, but instead they find an environment that only magnifies their respective strengths and weaknesses. The disconnect between the values of the agrarian environment and the city is made clear in one exchange between Rocco’s brother Vincenzo (Spiros Focás), and his fiancée, played by the luscious 21-year-old Claudia Cardinale.

“A real man takes the woman he wants without asking permission,” Vincenzo says, earning himself a fast shot to the chops. “With me,” she replies defiantly, “you have to ask every time.” Point taken.

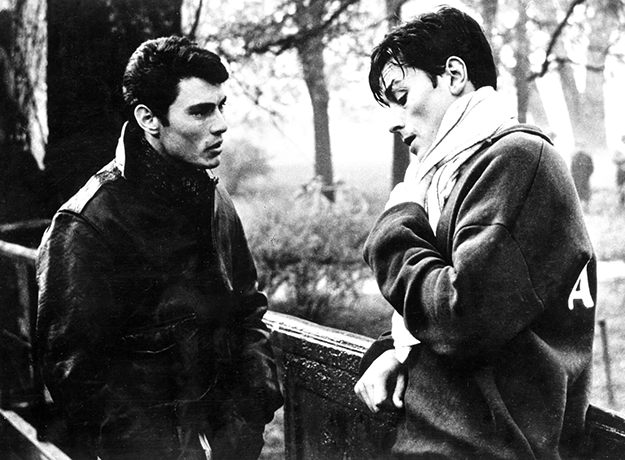

Milan is not the Oz they have imagined, but rather a mélange of hideous public housing developments. There is no work, so Simone—handsome, charming, and all too aware of it—becomes a boxer, while Rocco works menial jobs to support the family as best he can. Rocco, played by Alain Delon, has the face of one of Caravaggio’s dark angels. He’s the good son, the caretaker, and his rise is slow but sure until he falls in love with a prostitute (Annie Girardot) with whom Simone (Renato Salvatori) had a brief liaison. It is here that Rocco and His Brothers ascends to the torrential emotions of Verdi and Victor Hugo, as the Parondi’s collapse into interlocking antagonisms.

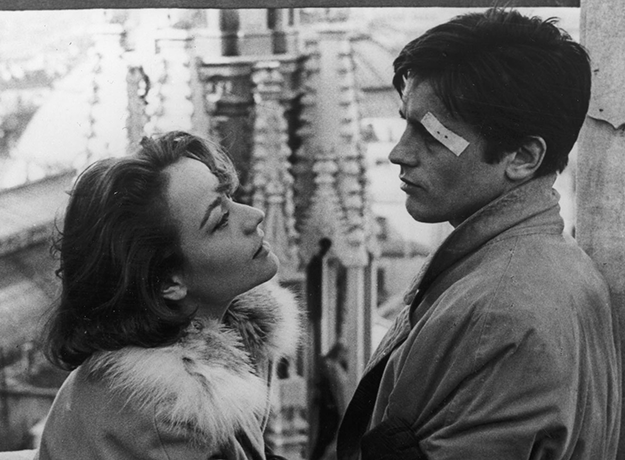

Scorsese aside, the American director who most resembles Visconti is Francis Coppola in his Godfather films. Certainly, there is more than a touch of Don Fabrizio from The Leopard in Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone—idealistic heads of dynasties who have outlived their time and know it. Both Visconti and Coppola favor a centered camera, the better to absorb the accumulating emotional upheavals; both feature brother betraying brother, and expansive long shots at crucial dramatic moments. Rocco renounces the woman he loves on the roof of the Milan cathedral, and Visconti’s images of jagged Gothic spires duplicate Rocco’s agony.

As the Parondis ponder their lost paradise—the foundational story of Western civilization—the film ascends to ravaging tragedy. “Ours is the land of the olive tree, the moon, and rainbows,” Rocco says, remembering their small town. And then he utters the sentence that eerily foretells the destructive tearings of the 21st century:

“We’re no longer in God’s grace. We’re our own enemies.”

Scott Eyman is the author of John Wayne: The Life and Legend, as well as 12 other books about the movies. He teaches film history at the University of Miami.