Readings: The Red Years of Cahiers du cinéma (1968-1973)

This article appeared in the April 7, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

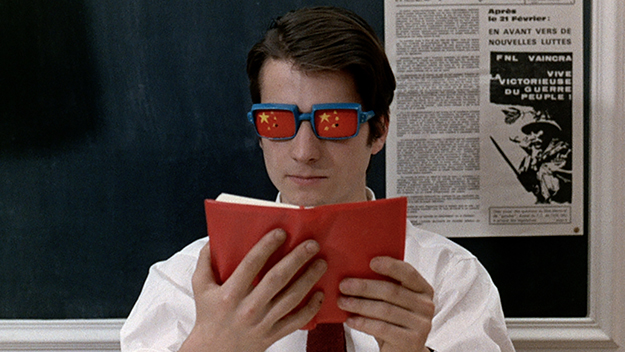

La Chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

The Red Years of Cahiers du cinéma (1968-1973)

Daniel Fairfax. Amsterdam University Press, $241

In 1991, when Antoine de Baecque, a future editor in chief at Cahiers du cinéma, wrote his history of the legendary French film magazine, he deemed it necessary to commit two large volumes to the project. Volume one—appropriately wrapped in a Cahiers-yellow dust jacket with a young Jean-Pierre Léaud peering out at the reader—dedicated roughly 320 pages to the journal’s most star-studded period, from 1951 to 1959. The second volume, which covered 1959 to 1981, donned a La Chinoise–red dust jacket with a still from that film, boldly announcing the political shift the magazine was to undergo. However, this second volume, while covering nearly thrice as many years as the first, had a similar page count. De Baecque’s preference for one epoch of the journal over another was clear: the radicalized Cahiers didn’t carry the historical significance of the “Young Turks” period. Given this slight, Daniel Fairfax’s likewise two-part The Red Years of Cahiers du cinéma (1968-1973) comes as a welcome riposte and a valuable contribution to the historiography of this amply documented journal, addressing what is, oddly, one of its least explored periods.

Fairfax divides his project thematically, with volume one dedicated to ideology and politics, and volume two tackling ontology and aesthetics. While this bifurcated tome is somewhat intimidating at first glance, with upwards of 800 pages of engagement with a notoriously difficult period of film theory, Fairfax has written an eminently readable and enjoyable text. The book presents an intellectual history of the journal’s theoretical-critical movement, from its post-’68 turn to Marxism-Leninism to the informed cinephilia of the late 1970s and early ’80s. However, Fairfax is careful to point out that his book does not chart “the evolution of the journal as a story of fall and redemption” as some have characterized it. What Fairfax demonstrates is that the theoretical work of those filmmakers and critics who participated in the sometimes dogmatic and sectarian project of the red years continued to be informed by the experience.

One of the key elements of the first volume is a series of readings of some of the journal’s best-known texts, in particular Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni’s editorial-cum-manifesto “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism” and the collectively penned “Young Mr. Lincoln de John Ford” (1970). The former essay appeared in the October 1969 issue of Cahiers du cinéma and was essentially an explicit announcement of the publication’s committed turn toward the far left as well as a response to political chiding from its rivals at the militant leftist film journal Cinéthique. Calling on an Althusserian critique of ideology, the short text outlined a nascent taxonomy of possible political films, organized along the axes of form and content. The editors pointed to inherent ideological weaknesses in each of the categories, except for one, which was composed of those films championed by Godard, Truffaut, and the other “Young Turks.” Ultimately, as Fairfax astutely notes, despite “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism” being the product of the journal’s most overtly left-wing editorial board, the essay also allowed the Cahiers editors to “critically recuperate the journal’s historical canon of classical auteurs.”

The Young Mr. Lincoln text also wore its auteurist fidelity on its sleeve, and, per Fairfax, “represented the most in-depth critical analysis of a film to appear in Cahiers up to that time.” Here, critics employed the methodology outlined in “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism” to analyze John Ford’s classic film, employing a collective process of critical writing. Fairfax notes that while there were other early examples of joint texts (“Cinema/Ideology/Criticism” being one of them), “the Young Mr. Lincoln article was the first time that a text was considered as the collective endeavor of the entire editorial committee.” “Collectivity” was a term loosely applied to many alternative film practices in those years, but there was often confusion as to how collective work was actually organized and what the division of labor looked like. Fairfax gives us a glimpse into the horizontal editorial structure at Cahiers and its day-to-day functioning. He quotes one of the principal critics at Cahiers during the red years, Jacques Aumont, on the process of writing “Young Mr. Lincoln de John Ford”: “We were all seated around a table, somebody suggested a phrase, somebody else said, ‘No, how about this?’ And by the end we had no idea who had written the phrase. It was really the only time I have ever experienced that.”

Volume Two takes us from a Cahiers radicalized by the events of May 1968 to one aligning itself with the psychoanalytic and deconstructive critical theory of Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, and Philippe Sollers, as well as chronicling the journal’s growing focus on world cinemas. This volume, like the first, offers a series of biographical sketches of the magazine’s major critics during this period. Maybe the most fascinating of these sketches is the chapter on the “kooky oddball” Jean-Pierre Oudart, who has long remained an elusive figure in Cahiers’ history. Oudart was responsible for writing “La suture,” a text that “represents the inaugural attempt to apply [Jacques] Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory to an interrogation of the basic functioning of the cinema.” The essay is a perennial inclusion in most “Introduction to Film Theory” collections, and Oudart’s name is almost synonymous with it. However, Fairfax points out that while Oudart “signed his name to more than 80 articles for the journal between 1969 and 1980, he never published elsewhere, and after 1980 the silence from the critic is total.” In place of a list of facts, the book constructs a kind of aesthetic theoretical biography of the writer: “there is also a change in the filmmakers that find favor in Oudart’s eyes: Godard and Straub/Huillet are seen in an increasingly negative light, while the critic takes a vivid interest in the works of Kubrick, Kramer and Syberberg. The rejection of some of Cahiers’ totemic directors would come at a price, however. As the decade came to a close, Oudart found himself increasingly marginalized within the journal, a lone voice at odds with the critical consensus that otherwise prevailed.”

The book closes with a discussion of Serge Daney, who was a principal figure at the journal during the red years. Beyond his militancy, Daney retained a great respect for the “Young Turks,” and after leaving Cahiers he wrote for the left-wing French daily Libération. Eventually, he founded the film journal Trafic, just prior to his death from complications of AIDS in 1992. Though no longer explicitly Marxist-Leninist, Daney’s writing continued to maintain a fidelity to that period at Cahiers, and Fairfax notes that “the profile of Trafic uncannily resembles that of Cahiers in its ‘red years’: at Daney’s behest, the journal is obstinately free of images, printed on rough paper, with an austere, brown cardboard cover. Its readership consists of a small band of loyalists, with a subscription base measuring in the hundreds, and it is maintained partly through the forbearance of the publisher…” By ending on Daney—whose foundational writing draws a straight line from the red years of Cahiers through the journal’s many evolutions and descendants to the criticism of today—The Red Years of Cahiers du cinéma demonstrates that whether Maoist, Althusserian, Rohmerian, Tel Quelian, or Bazinian, the Cahiers du cinéma of the 20th century continues to shadow contemporary film criticism, film politics, film history, and everyday cinephilia.

Paul Grant is the author of Cinéma Militant: Political Filmmaking and May 1968. He teaches film and literature at Kiuna College in Odanak, Quebec.