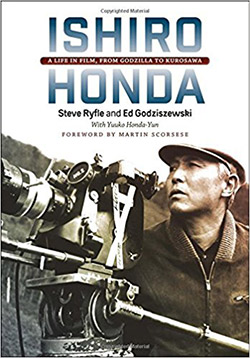

Readings: Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa

By Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski, Wesleyan University Press, $32.95

By Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski, Wesleyan University Press, $32.95

Ishiro Honda, best known for helming Godzilla (1954), spent a large part of his film career working as assistant director to Mikio Naruse, Akira Kurosawa (his slightly younger best friend), and other luminaries of Japan’s cinematic golden age. His greatest teacher however, was Kajiro Yamamoto, a career studio director who didn’t garner critical praise on the level of Yasujiro Ozu or Naruse. Yamamoto is notable for planting the seeds for the next generation that would bring Japanese film to worldwide audiences, serving as mentor to Kurosawa and Honda. That such diverse talents as these two could spring from a single sensei is a testament to the man. Of the two, Honda’s career more closely resembled Yamamoto’s, and he too became a dependable studio director, moving from one assignment to the next. Yamamoto-san taught Honda that any story should be able to be told in three sentences. Following that rule: Ishiro Honda was born the son of a Buddhist monk in a rural village of 30 families and became enamored with the movies at an early age after moving to Tokyo. After military service and the horrors of war interrupted his film career, he went on to make some of cinema’s most beloved works of fantasy. In the last phase of his life, Honda reunited with his best friend and helped to create, in a role that cannot be overstated, Kurosawa’s final masterworks.

Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s briskly paced new book, Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa, accomplishes a lot in under 350 pages. Perhaps most impressively, it provides the reader with a lasting sense of the man—his temperament, values, philosophies, dreams, and disappointments—behind some of cinema’s most beloved characters (Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra), while also exhaustively detailing the lifelong Toho director’s entire body of work (much of which is unavailable in the U.S. and even Japan). All of Honda’s films, from his early docudrama such as The Blue Pearl (1951) to the majestic fantasy of Mothra (1961) and Rodan (1956), to more “psychotronic” offerings like the infamous Matango (aka Attack of the Mushroom People (1961), are chronicled and critically appraised by the authors.

Mothra

The genres Honda flourished in were seemingly disparate. He was a skilled maker of the shoshimin-eiga (working-class dramas), but it’s the kaiju-eiga (large monster) and tokusatsu (special effects) films, which he helped to pioneer with effects master Eiji Tsuburaya, that define his legacy. Because of his background, Honda’s heart was in stories of the working class and familial conflicts, people’s connections to their traditions and to the earth. Honda’s dramas usually ended on a positive note of intergenerational understanding and cooperation, and the beautiful landscapes of the Japanese mountains and countryside would almost always find a place. After his time in the military, where he oversaw a station of comfort women (something he would later write about in an essay for Movie Art magazine in 1966) and witnessed the horrors of Hiroshima firsthand, Honda was then qualified to make another kind of film, beginning with 1954’s groundbreaking Godzilla.

Honda maintained a lifelong interest in the positive possibilities of science for humanity and sought to give Japan’s first foray into monster movies a sense of plausibility and authenticity, and Godzilla is one of cinema’s most lasting allegories on nuclear war and science gone wrong. Throughout his kaiju-eiga work Honda would consult with scientists and academics to give his scenarios at least a basis in reality. Dramatically, he sought realism as well, directing his performers to react as they would in each situation, no matter how unbelievable the scenario. Honda’s experience in shoshimin-eiga informed the personal drama of his fantastic scenarios, and Godzilla certainly benefits from his sober approach to the drama, as well as the dark and moody camerawork of Mikio Naruse’s cinematographer Masao Tamai. A brooding vision of unstoppable destruction unleashed by humanity’s technological hubris, the film was a major success for Toho, and ranked among the year’s top box-office performers alongside Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. The movie and the character’s legacy was cemented by another fact, though: it became the most widely distributed Japanese film in the West, albeit in a modified form (Godzilla, King of the Monsters!).

As Godzilla gained a life outside of Honda, the series became increasingly geared toward children. The character transformed from mother earth’s radioactive avenger into a lovable superhero. Honda returned to the series again and again attempting to maintain the integrity of it, lobbying hard against any humanizing of the creature. He also created some of cinema’s other great monsters in Mothra and Rodan. These films, free of Godzilla’s celebrity baggage, were works of elegant fantasy and claustrophobic dread, respectively. With every assignment, Honda tried his best to approach it thoughtfully, taking his films and monsters very seriously. He was introspective and measured in his direction, and Ryfle and Godziszewski’s book is filled with countless testimonials on “Honda-san’s” good nature and patience. He was, however, not completely satisfied with his lot. The pioneer and master of the kaiju-eiga yearned for something more throughout his career, a return to the kinds of movies he truly wanted to make: light dramas and films that used the power of special effects for something beyond monster destruction.

Terror of Mechagodzilla

In one of Honda’s final Godzilla entries he seemed to find a balance. A beautifully modest work that functions as both kaiju-eiga and shoshimin-eiga, All Monsters Attack (1969) was still geared toward children, but it wasn’t condescending. The film follows a latchkey kid (a social problem in Japan at the time that checked a requisite box for Honda’s dramatic intent) who fantasizes about a world of heroic monsters. He learns lessons of courage from Godzilla and his son, Minilla, and returns to his reality with the strength to stand up to bullies and kidnappers.

After 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla Honda seemingly retired from filmmaking, although he kept on at Toho recutting his classic movies for the studio’s popular Champion Festivals and working on spin-offs of his friend and collaborator Tsuburaya’s Ultraman series. Eventually, though, Honda reunited with Kurosawa, and the two embarked on a final adventure in moviemaking. At a low point in his life and career, Kurosawa was at last able to gain financing for films on the scale he was hoping for—epic period pieces filled with massive battles and unrivaled pageantry. He invited Honda, his golf buddy and dear friend, with whom his relationship had recently been rekindled, to be his collaborator on the films to come including Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985). Honda nonchalantly agreed, and the two disciples of Yamamoto, their beloved journeyman mentor, embarked on a series of movies that would bring Japanese cinema new attention and accolades. Honda was uniquely skilled at handling Kurosawa, the aging enfant terrible. After all, he had spent much of his life and career wrangling Godzilla.

Chris Shields is a New York–based filmmaker and writer. He is a frequent contributor to Art & Antiques magazine and Screen Slate.