Queer & Now & Then: 1987

In this biweekly column, Michael Koresky looks back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

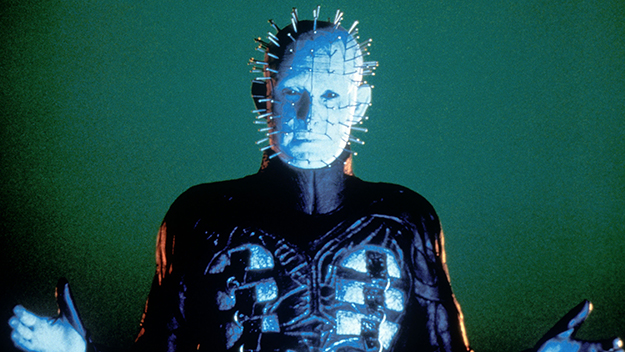

Images from Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987)

Maybe it’s hard to look past the gobs of viscera, but one rarely sees Clive Barker mentioned on any list of out-and-proud filmmakers of the last 30 years. An auteur of literally gut-wrenching cinema, the British horror and fantasy author and sometime movie director might not seem to check the boxes for our preferred standards of gay positivity, but shred through the pulp and gore and you’ll find the beating heart of a true queer auteur. His directorial debut, Hellraiser, is perhaps remembered to the casual viewer as the franchise-building breakthrough that introduced to the world to that prickly horror icon who’d come to be nicknamed “Pinhead”—against Barker’s desires—perhaps the quirkiest of all the antihero monsters in the gore-saturated era of Freddy and Jason. But Barker’s film stands well apart from the slasher teases of the ’80s in its willingness to engage more directly with discomfiting ideas about our viewing relationship to horror. Even more so than Cronenberg’s heady Videodrome, the less reputable Hellraiser is perhaps the most hardcore S&M mainstream movie ever. That Barker’s film couples that sadomasochism with a heavy dose of homoeroticism makes the film even more singular, an unapologetic, impolite violation of heteronormative standards smuggled into a wide-release genre framework.

A first-time feature filmmaker previously known as a writer of short stories and novels—including The Hellbound Heart, from which Hellraiser was adapted—Barker offers a steady stream of inventive gross-outs that, in their way, are as transgressive as those of John Waters, yet without any veneer of cuddly camp to make them accessible. In his narratives, and certainly in the Hellraiser films, he draws a distinct line between this world and the other—a monstrous nether region that speaks to human desire as much as fear. The films aren’t subtle in their inquiry into the thin bloodred line between pleasure and pain; “Pinhead,” leather-clad emissary from that other world, foregrounds that ad nauseam in his pompous Sadean declarations. Unlike in most other horror films, agony is as sweet as it is terrifying, and here it isn’t necessarily visited upon the innocent, but those who dare to go beyond the limits of their daily lives. Hellraiser isn’t queer just because its writer-director is gay (Barker would officially come out of the closet five years after its release), but because of its punkish sexual abandon. The frightening creatures of the underworld—known as the Cenobites—are figures of erotic exhilaration as much as terror.

The first and last lines of dialogue in the film are the same: “What’s your pleasure?” This is initially stated in the film’s traditionally Orientalist prologue, in which we briefly see a handsome, five-o-clock-shadowed Caucasian man, Frank (Sean Chapman), buying a strange object, an exotic puzzle box, from a mysterious merchant somewhere in the “Far East.” Almost immediately, Frank, is on the floor in an attic somewhere; he’s sweaty and stripped to the waist, kneeling in an onanistic pose. He holds out his newly acquired toy as though he’s about to begin a religious rite. It’s never completely clear why he forked over so much cash for this object, but he has evidently been promised some kind of forbidden ecstasy. Once opened—or “solved,” though it doesn’t seem like it takes much more than a brief touch to set it off—the box opens some kind of portal, the first indication of which is the film’s most nauseating recurring conceit: sharp fish hooks in close-up tearing and pulling at human skin. The imagery is familiar from extreme acts of sadomasochism, of flesh pierced, torn, and expanded. Barker has said that he got inspiration for the film from visiting an underground sex club in New York called Cellblock 28. Admitting that it wasn’t entirely just research, he added, “On S&M’s sliding scale, I’m probably a 6.” In Hellraiser, the level of endurance goes well past 10.

After the glimpse of Frank’s enraptured torment, we’re settled into a seemingly unrelated narrative. A forty-something couple—Julia (Claire Higgins) and Larry (Andrew Robinson)—is moving into a suburban house that formerly belonged to Larry’s missing brother. We quickly come to realize that the brother is Frank when Julia finds photographs of him indulging in various sexual pleasures with a succession of different women. Bodice-ripping flashbacks of a rain-soaked Frank in a leather jacket showing up at her back door soon clue us in that Julia herself had a passionate affair with her husband’s brother, and she can’t get the stud out of her mind. Recalling a passionate bout of sex with Frank, compared to whom the doofy-dad Larry seems particularly anodyne, Julia gets hot and bothered, whipping herself up into erotic frenzy. Barker intercuts her lusty memory with Larry slicing open his hand on an exposed nail while moving furniture into the house—sex and blood intermingled. Blood from Larry’s open gash drips onto the attic floor, on the spot where Frank had earlier opened the puzzle box, and absorbs directly into the wood; in the book, Barker makes it clear that the blood mixes with traces of Frank’s semen still on the floorboards. According to the film’s surreal go-with-it logic, this somehow creates a portal through which Frank manages to escape the Cenobites and crawl back to this dimension. In a gloriously disgusting bit of practical effects magic, his body begins to put itself back together, at first just a mess of disconnected limbs and an exposed brain. Gradually the form becomes a skeletal, gooey approximation of the once hale and hearty hedonist, his body since pulverized and stripped from his experiences in eternal damnation.

The gelatinous Frank creature convinces Julia to help him become whole again, and driven by the urge to see, feel, and fuck him once again, she agrees, even if it means bringing him live bodies to feast upon. “Every drop of blood you spill puts more flesh on my bones,” he explains. Driven by carnal appetites, Julia—who’s introduced as an ice queen so cold that she doesn’t even offer the furniture movers a beer—seems to have less conflicted feelings about this than she should. It’s like a homoerotic variation on Little Shop of Horrors: Julia thus begins picking up random men at bars and bringing them home, only to then hit them with a hammer and feed them to the hungry man in the attic. Their devoured blood and guts then repair Frank piece by piece, vein by vein. It’s an extraordinary depiction of bisexual transference, transgressing past the expected hetero consummation; at one point Frank pushes one of the victims up against the wall and, from behind, penetrates a hole in the back of his head with his finger while he’s still alive.

If there’s an innocent hero in Hellraiser, it’s Kirsty (Ashley Laurence), Larry’s teenage daughter. It’s via Kirsty, inadvertently, that the Cenobites eventually re-emerge: after happening upon the repulsive Frank in the attic, the young woman steals the Pandora’s box from him, passes out, and ends up in the hospital. Out of curiosity, she solves the puzzle, opening a portal in the wall and summoning the creatures. Barker excels here at creating standalone images of nightmarish poetry, such as the visual rhyming of a blossoming carnation and an IV drip filling with blood. It’s worth noting that the overall visual scheme of the film connects to the British queer cinema lineage of the era—its art director Jocelyn James’s next film would be Terence Davies’s Distant Voices, Still Lives, and its production designer Michael Buchanan helped craft the otherworldly looks for Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio, Ken Russell’s Gothic, and Sally Potter’s Orlando.

Then the dreaded beings appear. In a highly suggestive phallic image, one of the monsters—an eyeless fiend whose gruesome makeup design stretches its lips to eternity, so all that’s left on its face is a set of horribly chattering teeth, all appetite—sticks two fingers in her mouth to staunch her screams. The most loquacious of them, the one now known as “Pinhead” (a patrician, elegant Doug Bradley), his torn, bloody nipples peeking through his leather-daddy outfit, rudely gives only the barest of backstory, explaining that they’re “demons to some, angels to others”—intimations of specifically Christian hell and damnation. Politely refusing their invitation to “come with us, taste our pleasures,” Kirsty makes a deal that she’ll return the tormented Frank in exchange for her life. Likely a 1 or less on the pain-endurance scale, she’s better off throwing her uncle under the bus, anyway.

Barker’s equation of eroticism and blood is particularly powerful for a film released at the height of the AIDS crisis, and it could be taken as either a transgression of all sexual mores in a time of increasing homophobia and puritanism, or a moralizing commentary on the dangers of sexual licentiousness. Even though Kirsty can be read as a representation of sexual purity—and therefore she, of course, lives at the end—it’s hard to deny that Hellraiser’s appeal lies not in the vanquishing of sadomasochistic erotic temptation, but in its possibility. In many ways, Pinhead, who promises emotional and erogenous release at the same time that he guarantees eternal torment, is an incarnation of that age-old Victorian dandy Dracula. The Hellraiser series would continue with multiple sequels—as with any horror franchise, the monster proves unvanquishable. And we wouldn’t have it any other way: in a strange form of reverse wish fulfillment, we want the repressed to keep returning, providing us yet another opportunity to push past our earthbound limits.

Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer and Now and Then; and the author of Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press, 2014.