Queer & Now & Then: 1981

In this biweekly column, Michael Koresky looks back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

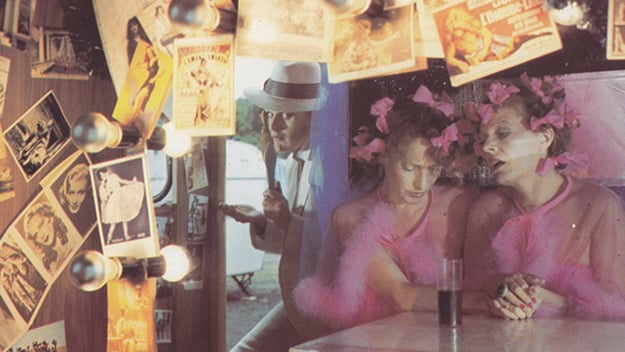

Images from Freak Orlando (Ulrike Ottinger, 1981)

“Beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror.” A meaty, provocative remark, and an idea that feels summative when uttered in the final movement of Freak Orlando, one of Ulrike Ottinger’s pleasurably disreputable bits of historical and narrative blasphemy. In her cinema, as well as her photography, Ottinger interrogated standard definitions of beauty and sexuality, and this 1981 epic of monumental irreverence climaxes with the public staging of an aesthetic role reversal. In the last of five incarnations, the constantly regenerating title character has become the chic “Madame Orlando,” the host of an outdoor contest in northern Italy crowning The Ugliest Person of the Year.

The competition, we learn, is organized by the Ugly People Society, founded in the 19th century to encourage the hopelessly unattractive to marry one another, and therefore maintain a highly subjective visual purity. Decked out in a black and red vinyl dress, and flanked onstage by the “Freak Orlando Bunnies,” Madame Orlando introduces a series of viable contenders—leather boys on crutches, dancing miscreants, working miners who have the gall to be in their late forties. There’s no emotional aspect to any of this, no identifiable frustration or response: as with so much of the film, the contest is mere pageantry, at once manic and highly structured. Is the sequence a celebration of Otherness, or a mockery of the celebration of Otherness, a representation of how difference itself is co-opted and commodified into faux-festivity?

Ottinger’s films are so dogged in their refusal to fit easy categories—even within cinematic subgenres that thrive on excess—that they’re unlikely to fully satisfy anyone looking for easy political directives. Though throughout her career Ottinger, a New German Cinema director who should be more of a legend of the movement, never hid her own lesbian identity, she often rejected queer labels for her own films, comparing such categorization as “being put in a little drawer.” As much of the work for which she is best known predates the creation of a communal queer cinema, this isn’t a surprising or unusual stance, one that would be shared by Chantal Akerman. The eternally heterodox Rainer Werner Fassbinder might have also bristled at seeing his films put in similar boxes had he lived long enough to see it: after all, he never had any interest in being a member of any group he didn’t himself found. Furthermore, Fassbinder’s aesthetic queerness seems as much a symptom or reaction to a national project of artistic and philosophical recuperation—a radical outgrowth of what he and so many other radical, sexually fluid filmmakers were trying to achieve in the New German Cinema: the decimation of longstanding boundaries between high and low, a confrontation with a recent history that their country seemed all too willing to ignore, and a reconstituting of the questions around gender and performance that were present in German art before being wiped out in the rise of Nazism.

Ottinger, the daughter of a Jewish mother who miraculously survived the war by being sheltered by Ottinger’s gentile paternal grandfather, made films that questioned all forced social standards and which only tangentially, symbolically dealt with the war. Her work has always unfairly existed in the shadows of the male filmmakers in the movement; rather than the confrontational melodrama of Fassbinder, the historical hysteria of Volker Schlöndorff, or the voluptuous kitsch of Werner Schroeter, Ottinger offered her own particular kind of excess, a tendency toward the baroque more focused on bodies and physical textures. In her book The New German Cinema, Caryl Flinn writes of Ottinger as an essential figure of the movement’s tendency toward camp, which she says has been traditionally and wrongly considered the purview of male filmmakers: “Constructing camp as only a gay male phenomenon . . . feeds on the clichéd belief that only gay male culture is visible, or ‘out.’ Lesbianism is somehow tucked away in hard-to-find interior spaces of all-female clubs or feline-occupied homes.” It’s provocative to think of her work in this way as a kind of “lesbian camp”—which is how her 1978 debut feature Madame X, a gay female pirate pageant, has often been spoken of. Her frames, which can contain pleasure and horror, beauty and grotesquerie in equal measure, seem to exist out of time, condensing and collapsing eras, even centuries, into a kind of free-floating operatic excess. This timelessness is a powerful tactic in a cinematic movement for which recent national history was impossible to reconcile with or quantify. In the light of what happened in Germany in the middle of the 20th century, how can history itself seem like anything other than backward? And how can one represent the forward progression of time without a jaundiced eye?

Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando is a fitting source of inspiration, then, for Ottinger; it’s a work in which time is fragmentary, bendable, and entirely theoretical. Its title character is a figure of radical physical and emotional bearing, able to shift genders over the course of history, from Elizabethan England to the postwar England of the ’20s, when the book was published. Any screen incarnation of the character would have to be necessarily distanced and metaphorically evoked, as in Sally Potter’s 1992 adaptation with Tilda Swinton, a film both extravagant and tightly corseted at once; Potter’s movie, shuttling ahead breathlessly through epochs, maintained Woolf’s largely linear structure, at least up until Woolf’s remarkable, time-collapsing final chapter. For Freak Orlando, Ottinger takes the basic ideas of the character’s malleable gender and apparent time traveling—or perhaps immortality—as a literary anchor point, rather than as a literal narrative basis. This version of Orlando—wielded like the mythical figure of 20th-century queerness that Woolf’s character has become—is not concerned with the idea of progress or forward motion; Ottinger jumps around to different time periods, giving the sense of history all happening at once rather than in a straight line.

Freak Orlando is the second in what is often referred to as Ottinger’s “Berlin Trilogy,” after 1979’s Ticket of No Return, which uses a variety of distancing techniques, like clinical voiceover and stylized tableaux, to neutralize what might have seemed like an emotional, melodramatic story—a beautiful woman, played by Ottinger’s former lover, Tabea Blumenschein, who decides to drink herself to death. There followed the perhaps even more baroque Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press, a 1984 sci-fi parable that references Oscar Wilde’s legendary narcissist to create a deliriously queered satire on celebrity culture and capitalism, featuring the androgynous model Veruschka von Lehndorff in the lead role. Perhaps the most excessive in form, the five-part Freak Orlando functions as a catalogue of impieties with a collage-like feel, flamboyantly juxtaposing mythology, historical spectacle, and contemporary consumerist critique.

Ottinger uses the same actors to take on multiple roles in the film’s different epochs, most prominently the mesmerizing, bold-visaged Magdalena Montezuma (who appeared in smaller roles in films by Fassbinder, Schroeter, and Rosa von Praunheim) as the five gender-variable Orlandos, and the great Delphine Seyrig, Jeanne Dielman herself, who appears as various characters alongside them. Following a wraparound, gateway sequence in which Montezuma, donning a bicorne and carrying a walking stick, descends from a mountainside into a desolate landscape, Ottinger takes us to a modern-day shopping mall in Freak City, promising a “clearance sale of myths.” Here, Orlando Cyclopa works as a kind of allegorical cobbler, personally imprinting shoes with a huge iron mallet and anvil, aided by seven dwarf helpers. Run out of the store and into the countryside by angry, plastic-encased shoppers, Orlando Cyclopa vanishes into the trunk of a tree.

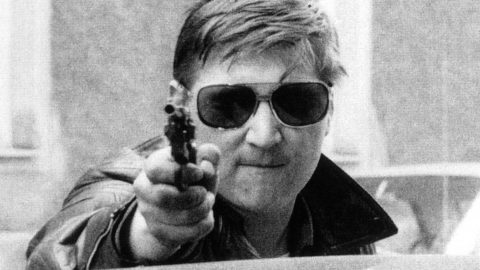

Fairy tale becomes indistinguishable from historical pageantry and profanation as the film wends its bizarre way through a series of episodic moments that show little reverence for religion or for cause-and-effect narrative progression. Eddie Constantine cameos as a saint who falls from his pedestal just at the moment that a hoard of self-flagellating pilgrims—depicted as shirtless rough trade guys in leather pants—have arrived from Freak City, whipping themselves into an ecstasy. A two-headed woman in medieval garb sings an exaggerated parody of an apocalyptic dirge (“the fish will scream in anguish”), against an industrial contemporary vista. A crucified, androgynous figure bedecked in softly glowing Christmas lights, based upon the Catholic female saint Wilgefortis, who was punished for growing a beard in order to avoid marrying, stops the show cold for an extended number, performed in an operatic-punk caterwaul.

Any description of the parade-like Freak Orlando necessarily turns into a checklist of oddities (monks carrying chickens with baby doll heads!), though as it continues, the film grows more richly funny, making room for a satirical domestic love triangle, in which a white-suited Mr. Orlando romances a traveling sideshow’s conjoined twins but gives a wedding ring to only one (played by Seyrig), before the climactic anti-beauty pageant. History is a circus in Freak Orlando. It feels like a film constructed of sketches from a troupe of traveling players. If used as an entry point into Ottinger’s work, it would be purposefully frustrating, often impenetrable, but also utterly representative. For the filmmaker—who started out in painting, photography, and performance art in Paris in the ’60s, before becoming disillusioned and moving back to Germany, where she worked in galleries and other curatorial roles, including founding a film club—cinema is a vessel for interpreting ideas rather than representing someone else’s idea of authenticity. She said, “In film, you can’t show things just ‘as they are,’ you have to do something with it, you have to condense reality.” Freak Orlando is her ultimate act of condensing, a film that feels jolted by future shock even as it exists in some indistinct, but distinctly queered, past. Watching it I was reminded variously of the chintzy satires of William Klein; of Fellini; the politically canny Varda of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t; the Buñuel of The Milky Way; Jodorowsky; even Monty Python… Yet none of these references defines or does proper justice to Ottinger’s singular vision of historical metamorphosis, a thing of uncommon beauty.

Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer & Now & Then; and the author of Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press, 2014.