Queer & Now & Then: 1956

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

Perhaps no Hollywood film better exemplifies the passive-aggressive game of hide-and-seek the industry has long played with queerness than Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 Tea and Sympathy. Based on a sensational 1953 play by Robert Anderson, this unorthodox ’50s movie melodrama is in some ways not all that thematically deviant from other American films of the era, such as Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger Than Life or Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind or Sidney Lumet’s adaptation of Miller’s A View from the Bridge, all of which are preoccupied with similar questions around American masculinity as a social construct. Yet in adapting the play, which directly dealt with taboo questions around homosexuality, Minnelli’s film at once plunges in and recoils from its own subject matter, resulting in a still-strange, heavily coded experience that’s neither here nor there—but which, thanks to Minnelli’s singular sensitivity and visually expressive style, remains a remarkable, compromised work of mainstream American filmmaking, further complicated by the matter of Minnelli’s now widely known closeted status.

Understanding a little about Anderson’s play will help elucidate the oddity of Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy, a highly talky film that’s nevertheless been gagged. Set within the tightly enclosed parameters of an all-male boarding school in New England, Anderson’s play concerns the vicious intimidation and bullying showered upon a shy, fey 17-year-old senior named Tom Lee. He isn’t like the other boys, preferring activities considered “feminine,” gravitating more to music and the arts than sports, and seemingly disinterested in girls. The meat of the narrative concerns his gradual bonding with the headmaster’s lonely wife, Laura Reynolds, a sensitive soul who lends a sympathetic ear to the boys, her tender presence intended to implicitly help the students better delineate male and female roles. Tom’s relationship with Laura is more complex, blossoming from maternal figure (the boy’s own mother abandoned him when he was five) to emotional companion to, finally, lover. All the while, Laura tries to help Tom as the student body begins to spread rumors of his alleged homosexuality, tagging him with the nasty nickname “Sister Boy,” which is clearly a euphemism for “Sissy Boy,” but also stands in for all the derogatory terms for “queer” that had been stricken from the play’s script in deference to the Motion Picture Production Code.

Anderson, who said he had been inspired by his own experiences in school and his relationship with an older woman, denied that Tea and Sympathy was a “gay play” and said it was about “a false charge of homosexuality.” In this way, as a story about the danger of the rumor mill, Tea and Sympathy is historically aligned with Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play The Children’s Hour, later made into William Wyler’s notorious 1961 film with Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine; now commonly derided as the quintessential dated portrayal of the “tragedy” of being gay, the film is also set in a private school and more preoccupied with scandal and mud-slinging than the emotional experience of otherness. Nevertheless because of the vacuum of representation that would continue for decades, the screen adaptations of these plays remain two of our most visible dramas related to issues around homosexuality, making them difficult texts to wrestle with and impossible to dismiss. Tea and Sympathy, first produced the same year as The Crucible, another drama of accusations and allegations against one’s good name, could be viewed more as thinly veiled post–McCarthy-era drama. Even if homosexuality—or, per the film’s hang-ups, insufficient male-ness—becomes implicitly the worst thing one can infer about you, there’s something expansive and moving about the film’s expression of outsiderness. It feels just as strongly today a film about identity and the inability of the oppressive American mainstream to allow for expressions of sexual or social individuality.

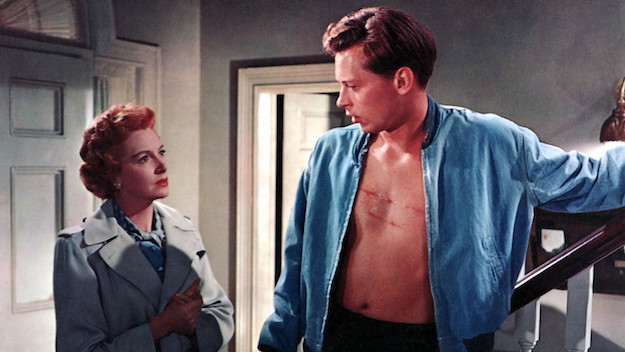

Despite Anderson’s downplaying his work’s overt gayness, the material was scandalous enough—also for its adulterous, May-December affair—that MGM was nervous about the property. In the movie, Tom is one crucial year older, though as embodied by 25-year-old newcomer John Kerr (who played the role on stage and had just appeared in a supporting role in Minnelli’s mind-boggling 1955 melodrama The Cobweb), he hardly looks so boyish that his age difference with Deborah Kerr, also reprising her Broadway role as Mrs. Reynolds and only 10 years his senior, produces any seismic shocks. One noteworthy change from stage to screen was the elimination of a small character, a schoolmaster named David Harris, believed to be a “fairy,” with whom Tom is allegedly seen romping naked on a beach. It’s this event that fuels the rumors that drive Anderson’s plot; without David Harris, the film is even more clearly about misperception and hearsay and social codes than gay sexuality.

As a way of imposing a kind of warm nostalgia and moral finitude around the play’s emotional minefields, Minnelli’s film couches the events in flashback, with a wraparound set at a school reunion that grants the closure the play wasn’t willing to provide, diluting and sanitizing an already delicate film reticent to delve into uncomfortable subject matter. At the same time, Minnelli uses the extra screen time in the opening scene to subtly elaborate upon his themes. As the grownup Tom wanders through the school grounds in the opening scene, bobbing and weaving amidst the now grown students who had terrorized him, we hear pockets of these handsomely suited former peers rhapsodize about “real men” and “beautiful girls,” creating an alienating effect for a hero we’ve barely met. After he peruses his former bedroom (with a suspiciously wistful air for someone so traumatized by his experiences there), Minnelli glides his camera through a window, deftly transitioning to the past as we see Deborah Kerr’s Laura Reynolds tending to her blooming garden while Tom serenades “The Joys of Love” on guitar. Early on we discover that Tom, with his green thumb and sewing skills, has advice for Laura and the other schoolmistresses and wives on campus, one of whom tells him he’ll someday “make some girl a good wife” while he threads her a needle. This exchange occurs on the beach, away from where the more bronzed and buffed boys are, gallivanting and horseplaying and tossing around a volleyball and laughing over a magazine quiz none too subtly titled “Are You Masculine?”. Soon enough his classmates are bullying and beating him, leaving “Sister Boy” with a bleeding lip and an irrevocably bruised male ego.

Laura increasingly feels driven to act as Tom’s protector and savior, partly out of obligation to her position at the school (she’s to stay mostly deferential to her husband’s authority but occasionally give the boys some “tea and sympathy”) but also because we discover Tom reminds her of her first husband, a sensitive man who was killed in the war “proving he wasn’t a coward.” While stopping short of defending him if he actually were gay—much like the film stops short of acknowledging gayness at all—Laura desires to speak on behalf of men who don’t conform to ideals of masculinity. When he visits, Tom’s straight-arrow father (Edward Andrews) bemoans his son’s differences (“Why isn’t he a regular fella?”), demands he get a crew cut like the other boys (“Why?” Tom simply asks, to which dad responds, “You just should”), and is hilariously horrified at Tom’s desire to be a . . . folk singer. Those final two words are delivered after a dramatic pause that can only register as near-satire. Likewise, a later scene in which Tom’s roommate Al (Darryl Hickman, so memorable as Gene Tierney’s disabled teen victim in 1945’s Leave Her to Heaven) teaches him how to “walk like a man,” resulting in some wooden lurches across the floor—neither the “masculine” nor “feminine” examples of walking registering as particularly natural—plays as comedy, not terribly far removed from similar scenes in later slapstick farces La Cage aux Folles (1978) and The Birdcage (1996). In moments like these, Tea and Sympathy feels knowingly absurd and aligned with the perspective of the outsider, making the film an unusually powerful evocation of feeling socially outcast in Eisenhower’s America, regardless of how unready Minnelli, Anderson, and MGM were to deal with the story’s deeper underlying themes.

In the film’s most disturbing scene, Tom is targeted during the school’s annual hazing event, the “bonfire pajama fight.” For this homoerotic ritual, it’s made clear, both by the student body and the faculty, that Tom will get a “real going over” and that it’ll be good for him. In this depiction of institutionally sanctioned violence and bullying, Tom is paraded out martyr-like for his fitting punishment. That Tom is made an example of during this elaborate show is all the more ironic considering that his father had forced him to drop out of the school play, School for Scandal, when he discovered he would be cross-dressing as the character of Lady Teazle. Not allowed to make a spectacle of himself on stage, Tom is instead, with the tacit approval of his father and the headmaster, made to perform as a victim for the delectation of the school. This is made more visceral on film than in the play, where the bonfire is spoken of but never seen. Minnelli makes the scene into a setpiece, visually evoking the always unsettling Halloween sequence in his own 1944 Technicolor musical Meet Me in St. Louis, and thus amplifying the horror.

Tea and Sympathy is often thought of as a hopeless relic, yet the way it teases and tiptoes is hardly a thing of the past in terms of cinema. For instance, it’s always been clear to me that Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society (1989) is cagey in its portrayal of Neil Perry (Robert Sean Leonard), the sensitive boy who’s into theater and poetry and whose demanding father disallows him from pursuing “this theater business” and forbids him from starring as Puck in Shakespeare’s hopelessly fruity A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As recently as 2014, gayness was withheld as a last-act tragic twist in the historical biopic The Imitation Game. It’s safer and makes us feel superior to write off a film such as Minnelli’s as “dated,” as though the way it frames an unapologetically patriarchal culture venerating masculine ideals has, at its core, changed very much in the 60-plus years since. According to biographer Mark Griffin, Minnelli would say publicly and proudly at a festival in the late ’70s, “I made the first homosexual picture while I was at MGM. That was Tea and Sympathy.” Regardless of its shortcomings by today’s standards, or even its limitations as an adaptation, that isn’t a sentiment simple to shake. Minnelli never spoke of whether he truly identified with Tom Lee, though auteur readings have necessarily created a connection between Minnelli, the window-dresser who became one of Hollywood’s great factory men (not to mention Judy Garland’s husband), and Tom Lee, who prefers to spend his allowance on curtains for his dorm room.

Our cinema still wrestles with the representation of women and queer characters, so the changes made to the last act of Tea and Sympathy from stage to screen carry a sting for contemporary viewers. Anderson’s play concludes with the intimation of sex between Tom and Laura, who ends the show with the famous curtain closer: “Years from now, when you talk about this, and you will, be kind.” Whether done out of grace or pity or genuine sexual desire—or all three—Laura’s initiation of their final congress is left to the viewer to interpret. Minnelli’s visual evocation of the scene is indeed gorgeous, taking place in a fairy-tale forest primeval, with ethereal light emanating from behind a tree as they embrace. Flashing back to the present, the film adds a final touch: a letter that Laura has written to Tom, read aloud by Deborah Kerr on the soundtrack while Minnelli’s camera takes in trees and flowers swaying gently in the breeze. From the letter it’s clear that Laura has been ostracized from her former life, living somewhere in Chicago, and that Tom has been sufficiently straightened out (“I was so pleased to hear that you’re married”). Imposed by the Production Code, this wrap-up existed in order to make sure audiences were aware that Tom had conformed and Laura had been punished for her adulterous transgressions. It all worked out; the New York Herald Tribune said the film, against all odds, demonstrated the utmost “good taste.” Tea and Sympathy shows eminent love and tenderness; being an American kind of love, it’s highly conditional.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to The Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.