Queer & Now & Then: 1949

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

Christmas U.S.A.

One of the most beautiful American films of the postwar era, Gregory J. Markopoulos’s 1949 Christmas U.S.A., in just 13 silent minutes, expresses more about the condition of the queer American male psyche than any feature-length narrative film of the time could dream or dare. A subjective evocation of a dream world in subliminal tones, Markopoulos’s film functions as a sort of inventory of a socially repressed mind, expressing entrapment and liberation, piety and desire. The contours of this film’s universe are ethereal and abstracted, yet the film grounds its young men’s emotional yearnings in concrete details of middle-American living. An experimental filmmaker whose work and life would become notoriously slippery over the next four decades, Markopoulos creates a grounded, richly tactile experience of pregnant looks and heartbreaking noncommunication in this early film. Christmas U.S.A. feels almost unbearably private, a movie that, despite its meticulous construction, is like a secret that has spontaneously appeared on screen.

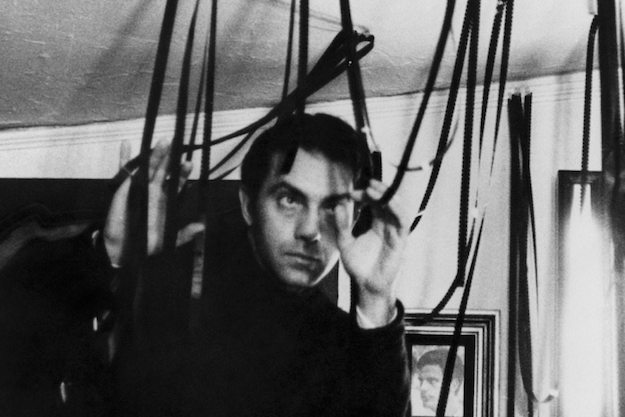

Christmas U.S.A.’s literal connection to the holiday itself is somewhat inchoate, only presumed, though the title does implicitly unite it with Markopoulos’s first film, a five-minute version of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1940) he made in his hometown of Toledo, Ohio, at the age of 12 on a borrowed 8mm Keystone camera. However peripheral the holiday feels while watching Christmas U.S.A. (it seems to regard Christmas as more a state of mind than a literal observance), it makes sense that a filmmaker so preoccupied with transforming small gestures into grand, mythic ones would make a pair of films centered around something as culturally symbolic, inescapable, and looming as Christmas. Markopoulos’s career would come to be defined by myth, tradition, and repetition, most famously in his absurdly massive magnum opus: Eniaios, a silent film made up of 22 cycles, running about 80 hours total, and projected only once every four years in an outdoor theater/archive space that Markopoulos created and named the Temenos (“sacred grove”) in the Greek mountain village of Lyssaraia; something like the world’s greatest cult film series, it continued to run even after Markopoulos’s death in 1992, thanks to the devotion of his partner, the filmmaker Robert Beavers. Eniaios may be his most lasting, elusive gift to world cinema, but his early works—which had been hard to see for so long due to Markopoulos’s demand that most of his films be taken out of circulation upon his relocation to Greece in the late ’60s—provide primal glimpses of an uncompromising (and daringly queer) mind at work.

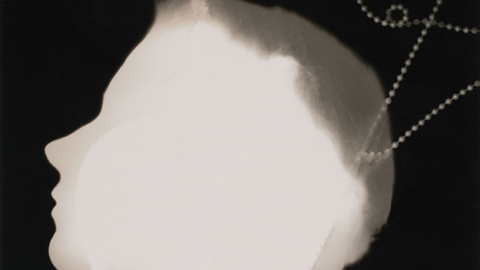

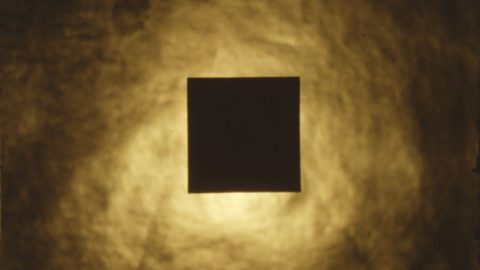

With its dreaming-and-wandering plunge into psychosexual interiority, Christmas U.S.A. evokes seminal American avant-garde films of the era like Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) and Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks (1947), but with an aching yearning for emotional freedom that feels all its own. Shot in Ohio—Markopoulos had recently returned after leaving USC—the film registers as highly ambivalent about home and family (it was partly shot in his family’s house). Christmas U.S.A. is cut in two, following a pair of handsome young men who may represent alter egos; each is defined by a symbolic split, embodying both inside and outside, domestic and wild, masculine and feminine. Markopoulos’s eroticism is far subtler than Anger’s, yet it’s throbbingly present. The first of the main figures, a brunet, stirs in bed, his sleep intercut with images of him traipsing through a traveling fairground, the “Cavalcade of Worlds.” Ferris wheels, spinning tilt-a-whirls, and other amusement rides are matched with rotating record turntables back in the house, visually uniting interior and exterior, reality and dream. We see glimpses of sex (a quick cutaway to an attractive carnival barker) and liberated alternative communities (a black-run attraction called “Little Harlem”), promising worlds away from home.

Gregory Markopoulos

Eventually, he gets out of bed and puts on slippers and a kimono, which he quickly covers with a more reassuringly masculine robe. After we see him shaving in the bathroom, the film cuts to him wandering through the woods—this time wearing just the kimono, proudly unconcealed—where he discovers a jeweled trinket cabinet surrounded by branches and dead leaves. Markopoulos indicates this isn’t necessarily a real space as he intercuts his perambulations in nature with shots of him back at the house, talking on the phone, while suggestively fondling a letter opener and ashtray (we never see who’s on the other line, though by the end we may hazard a guess). These strange totems and curios seem to open the film up to an alternative, or perhaps adjacent, world, as Markopoulos brings us into the more suffocating home life of another, younger man, a fair-haired teenager whom we first see longingly staring out his attic window (in an image that anticipates Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes). This boy’s own sexual urges are constantly set against images of his mother’s domestic work—vacuuming, setting the dining room table—often shot in tight close-up. The house at times has the feel of being haunted: at one point, the boy lies in the tub and notices that someone is fiddling with the doorknob, trying to get into the bathroom, but when he peeks outside the door, there’s nothing but an empty hallway, the image disorientingly sideways. Wrapped in a towel, he creeps out onto the shadowy landing—the only creature stirring is a mechanical little drummer boy perched on a small table, its wide Hummel-like eyes peering off-screen in a coy, knowing taunt.

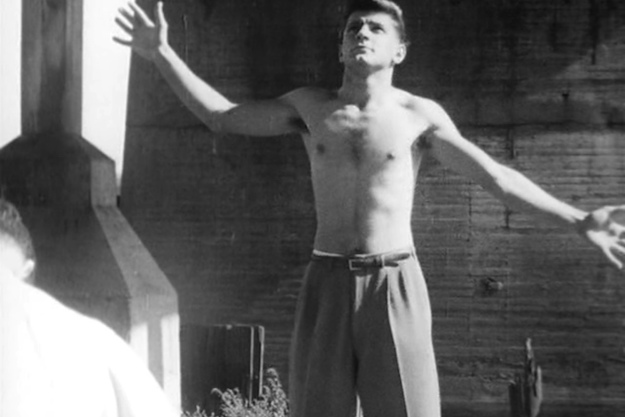

In an echo of the film’s first half, the boy projects himself wandering outside in a kind of symbolic liberation from stultifying drudgery. Here, he walks across back roads, over train tracks, and under bridges, carrying in one hand a long candlestick raised high. Finally he comes upon a handsome, shirtless man, standing stock-still beneath an abandoned underpass, his arms outstretched and head cocked upward in a pose of martyrdom that recalls St. Sebastian. He genuflects before this impenetrable beauty, an image of Christian desire and guilt, bowing and waving his candle back and forth over his shoulders in a visual gesture that communicates erection, prayer, and self-flagellation all at once. The saint is unresponsive, but in a briefly held composition we see him on the ground, our hero supporting his supine body in a near-pieta pose.

This encounter has the power of revelation, leading immediately to the film’s eloquent final moments. Back at the house, for the first time we see the boy’s father, chomping a cigar, staring at the newspaper, before looking up. A look of weary understanding passes between them. In a crucially definitive motion, the boy turns around and walks out of the room, and his father looks back at his paper. Back in the shadowy hallway, his mother and sister poke their heads out of their respective rooms, their faces dramatically, almost ghoulishly lit, at the exact moment to see him, coat buttoned, ready to leave the house. He looks back at them, but doesn’t hesitate. Something about it feels final, feels right. An onscreen closing title card reads, movingly, “the end of a period.”

Markopoulos would make richer, more complexly structured and radically edited films about the emotional burdens of desire and family, especially the epochal Twice a Man (1964), but Christmas U.S.A. holds an undiluted power and a particular fascination for boldly expressing such queer longing in the American 1940s. The film bristles with the kind of radical, repressed erotic energy one might feel looking at a painting or photograph by Paul Cadmus or Jared French. And, perhaps most unexpectedly, its climactic, salvational exit lends Christmas U.S.A. a surprising positivity, a sense of an adventure just beginning. Who knows if it’s really Christmas when he leaves the house, once and for all, but there’s no doubt that it’s a time of transition. A new year is coming.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to The Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.