Queer & Now & Then: 1942

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

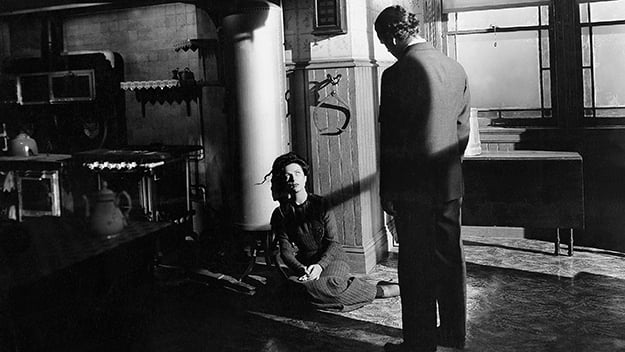

All images from The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)

The word “queer” is at once too big, too meaningful, and too vague to do all the work it needs to do. The way that “Q” perches at the end of “LGBTQ” like a squiggly little tail speaks to its general precariousness; it somehow risks overtaking the whole and being forgotten all together. Yet at the present moment, the term feels fully integrated into the overall discourse, richly inclusive, straddling academia and popular culture; the “Gay and Lesbian” Anthologies and Volumes of the ’90s have become the “Queer” Readers of the 21st century. The word, an indicator of how more speculative scholarship gradually filters down into definitive mainstream concepts, has a strange, malleable currency: it has become a significant shorthand of solidarity, not only for members of the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender communities but also for the essential questioners of the dominant heteronormative procreative culture that has historically swallowed all non-binaries whole. The word follows in the great legacy of originally derogatory terms weaponized in self-defense by those they were used against, and the recouping feels nearly complete. “Queer” is therefore at once political, sexual, and psychological; it relates to gender; it relates to desire; to perspective; to identity; to contingencies of class, race, economics, nationality. It intersects with and encompasses all, promises everything, yet in a way, divulges nothing, because identity can never truly be explained away. It speaks to the past and represents the future.

All this is to say that the term queer is an individual political choice, and therefore it’s what you make of it. So what does it summon for you? For me, I am immediately reminded of a particular movie, one that features an offhanded yet significant use of the word that’s evidently divorced from its current meaning, and it’s certainly a film one would never put in any “queer canon.” Nevertheless Orson Welles’s 1942 The Magnificent Ambersons gets me thinking about the meaning, history, and context of the word every time I see it. Taken away from its maker and butchered by anti-art studio men nervous after negative test screenings, The Magnificent Ambersons is a notoriously sullied American film that’s nevertheless so spectacularly realized that nearly every other “intact” movie seems comparatively a shambles. The Magnificent Ambersons is a bit of a queer object in itself, its production woes exemplifying Hollywood’s essential fear and conservatism, and a victim of unapproved cutting that has found its strength and voice over subsequent decades.

The word “queer” comes—and is repeated—at a crucial early moment in the film, and one could even argue that it’s a symbolic instigator of the narrative’s central conflict. Faithfully adapted from Booth Tarkington’s 1918 novel, Welles’s claustrophobic turn-of-the-20th-century saga is preoccupied with change, both incremental and epochal, and the consequences for those who resist. The central resister is George Amberson Minafer, misguided keeper of the flame, both for his once proudly wealthy Midwestern family and a vanishing way of life. Seeing himself as a righteous upholder of traditional values and virtues, George (Tim Holt, marvelously rigid in embodying what Tarkington described as George’s “imperious good looks”) is actually a typical spoiled brat whose privilege has done little more for him than stoke his ambitions to become a “yachtsman” when he grows up. Back in town for his family’s Christmastime homecoming party—“the last of the great Amberson balls,” as Welles’s mournfully eloquent narration puts it—George espies a guest he’s never seen before, played by Joseph Cotten. To us the man seems a pleasant-seeming chap, but to George, instantly judging him as an interloper, he’s a “queer-looking duck.”

The words are foregrounded, repeated enough to not be missed; indeed they come straight from Tarkington’s book. The term “queer-looking duck” appears in the novel no less than 13 times before we, along with George, learn who he is. The appealingly cartoonish combination of the words “queer” and “duck” charges the scene with a lively humor, as does the fact that George relates his smug observation to Lucy Morgan (Anne Baxter), the young woman he’s eagerly courting, not knowing that the “queer-looking duck” is actually Lucy’s father. Now a widower, Eugene, who has returned to town after a two-decade absence, once courted George’s mother, Isabel Amberson Minafer (Dolores Costello), a history which only intensifies the possessive, unrelenting, and territorial George’s dislike of him. In the younger man’s eyes, Eugene’s queerness comes from his outsider status, tagged both to George’s classist perception of him as a social climber and to Eugene’s fishy career: he’s the inventor of that infernal, unnecessary thing called an automobile, aka the horseless carriage.

There would seem to be more playfulness than malice in Tarkington’s use of the word, yet George’s proclivity to insult and patronize nearly everyone who isn’t him lends his every colloquialism an unsettling pejorative air. Tarkington, invested in what was in and out of fashion, takes more space to contextualize the word that “queer” is qualifying:

Undergraduates had not yet adopted “bird.” It was a period previous to that in which a sophomore would have thought of the Sharon girls’ uncle as a “queer-looking bird,” or perhaps a “funny-face bird.” In George’s time, every human male was to be defined, at pleasure, as a “duck”; but “duck” was not spoken with admiring affection, as in its former feminine use to signify a “dear”—on the contrary, “duck” implied the speaker’s personal detachment and humorous superiority.

So the choice of word is precise; it has the power to mock and wound. Our words are inextricable from how we socially code outsiders and box in gender. Queering the already infantilized, emasculated “duck” only makes it all the more ridiculous. But what makes Eugene such a “queer-looking duck”? According to Tarkington, “The duck parted his thick and longish black hair on the side; his tie was a forgetful looking thing, and his coat, though it fitted a good enough middle-aged figure, no product of this year, or of last year either.” Joseph Cotten, whose costume appears fairly au courant and whose hair is hardly as exotic or unkempt as Tarkington described, cuts a more dashing figure as Eugene, yet he remains a queering agent for the film, and for the family. As is always the case in our world, the destroyer will not be the supposed outsider, but the accuser, using his prejudice, paranoia, and self-interest to tear down the walls of his own empire brick by brick.

Other written instances of “queer”—whose origin is given by the Oxford English Dictionary as 1513, and which the original, “chiefly British” Merriam-Webster entry defines as “questionable,” “suspicious,” “sick,” and “unwell”—help to elucidate the acidity of a word that some may assume was simply at one point an anodyne synonym for “unusual.” Late in Edith Wharton’s 1905 masterpiece The House of Mirth, for instance, social-climbing Simon Rosedale—already an outsider due to his Jewishness—refuses to marry increasingly desperate heroine Lily Bart because of her newfound pariah status in New York’s high society, cruelly telling her, “I’m more in love with you than ever, but if I married you now I’d queer myself for good and all, and everything I’ve worked for all these years would be wasted.” In other words, queer Lily has the power to stigmatize others. A decade earlier, the Marquess of Queensberry chastised his son, Lord Alfred Douglas—remembered today primarily for being a lover of Oscar Wilde—for associating with “Snob Queers,” in an 1894 letter that’s generally regarded as the first recorded instance of the word used as a slur toward homosexuals.

Tarkington’s—or Welles’s—awareness of this legacy is less essential here than the fact of the word’s usage as a means of Other-ing, of creating an emotional quarantine. Within the world of Welles’s adaptation, it makes perfect sense for George to grow up an unrepentant bully: not only is he the product of blinkered privilege, but also we see in the film’s prologue that as a child his fancy, aristocratic airs and dress were roundly mocked as feminine by neighboring boys. “Look at the girly curls!” they tease him for his flowing blond locks and ostentatious Little Lord Fauntleroy dress. As an adult, perhaps in response, George assumes an intractable, manly persona; Holt rarely smiles in the film unless sneering at Eugene or at the easiest target of his mocking superiority, his high-strung Aunt Fanny (Agnes Moorehead, who can brilliantly modulate between crumbling fragility and take-no-guff wisdom in the blink of an eye). George’s default mode is indignation, aghast at all the insufferable people who would distrust or disregard his family’s honor—basically anyone but himself and his beloved mother. He demands respect even though nothing in his life gives the impression that he commands it.

George sees himself as upright and correct, as not queer like all the other ducks out there, but his defensive postures speak to a deeper need to assert masculinity. His insecurities around his manhood find their greatest challenge in his stunted romantic pursuit of Lucy; she’s played by Baxter with a devastating insouciance that the dense George takes as female unreadability, but which the viewer knows is couched in her profound distaste of him. Aside from his general charmlessness, George has only intensified his battle against Lucy’s father in the wake of his own father’s death, disallowing him from reigniting courtship of his mother. Nevertheless, George, convinced of his own righteousness, continues to pursue Lucy. Their relationship builds to a kind of surreal breakup scene, which Baxter performs in an unforgettable register, sporting a singsong voice and a guileless smile while she cuts him down. As they walk down a city street—she strolls, he trudges—he stops and grimly tells her he’s leaving town on an indefinite journey with his mother. George, in the foreground, says, crestfallen: “I think it’s good-bye for good, Lucy.” Lucy, in the background, grinning ear to ear, hands buried in a muff, responds: “Good-bye, George, I do hope you have the most splendid trip!” It’s perhaps cinema’s all-time greatest “fuck you,” and staunches what George might have seen as his last chance for romantic happiness.

The Magnificent Ambersons is introduced as a journey toward George’s “comeuppance,” which Welles’s narrator is all but delighted to tell us he receives “three times filled and running over.” Trying to walk tall, he’s cut off at the knees. For all his desperate need to maintain social status and keep the world in what he sees as tradition-minded balance, George foments nothing but discord, hastening the demise of a way of life that was already on its way out; by the story’s final movement he’s neutered, aligned most closely with “old maid” Aunt Fanny, probably the most socially queered of all the characters. George’s arc speaks to the backward progress destined to be experienced by those who would brand others as “queer ducks.” The film’s redemptive, tacked-on ending, imposed by the studio against Welles’s wishes, might indicate otherwise, but The Magnificent Ambersons is properly pitiless to George and to others who, like him, are left behind. In its inevitable forward march, history has no time for any sneering Ambersons. The queer ducks win.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to The Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.