Queer & Now & Then: 1992

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

Published in 1928, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando was written as a gift for the author’s lover of many years, Vita Sackville-West. If anything can be called furiously whimsical it’s Woolf’s book, which buffets its title character across centuries and between genders: Orlando starts as a man of privilege in Elizabethan England and ends as a woman of letters in the postwar 1920s. Orlando barely ages, even though he goes from lovelorn youth to frustrated poet to chic ambassador to lady of leisure to modern woman, the main constancies an artistic curiousness manifesting as a desire to write and a much remarked-upon beautiful androgyny. Woolf and Sackville-West, who socialized and discussed literature and culture as members of the thoroughly modern bohemian Bloomsbury Group—which also included the gay writer Lytton Strachey, critic Clive Bell, and Woolf’s sister Vanessa and husband Leonard—had a longstanding and, today, much documented mutual correspondence that extended beyond the boundaries of their courtship. But their romance remains a subject of great fascination to biographers and scholars of gay culture, and Orlando is its most lasting testament. Sackville-West’s son, the writer Nigel Nicolson, called the book “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature,” and indeed those of us with a romantic persuasion could hardly imagine a more complimentary creation than Orlando, who is not only the embodiment of creative passion and the finest physical specimen of either man or woman but also, evidently, immortal.

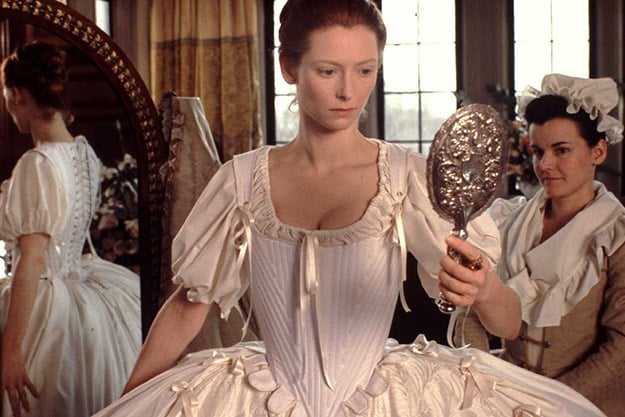

Already an icon of queer literature and culture, Orlando would also become a natural avatar for the New Queer Cinema that fully blossomed in the early ’90s. Sally Potter’s muted yet lavish 1992 adaptation of Woolf’s book stars a young Tilda Swinton, in a role that thrillingly exploits her exquisite androgyny. At this point, the actor was already aligned with the New Queer movement—her period-transcending visual impact had already been harnessed by the great Derek Jarman in such queer film landmarks as The Last of England (1987) and Edward II (1991). Though Swinton is a remarkably apt embodiment of Woolf’s creation, Orlando is probably impossible to fully translate to the screen; the particulars of plot, character, and consequence are not as compelling or essential to Woolf as the interior growth and ultimate exhilaration of her (finally female) protagonist—the elements that make it a feminist work. Potter’s film is somewhat faithful to the literal events as they unfold in Woolf’s book, but the author was writing about something difficult to literalize in a cause-and-effect narrative, which is that Orlando is a constant in a transitory world: his/her ability to traverse centuries, and therefore bear witness to enormous societal and political change, is not the result of fantastical intervention but, in Woolf’s philosophical framework, a natural outgrowth of the fact that time is a construct, elastic and false.

Narrative films often provide rationales for what we see, so Potter’s version invents a mildly abstract reason for the metaphor that is Orlando’s temporal singularity. In the film’s first section, which is introduced with the onscreen marker “1600” (Woolf was never so clear with exact dates in her breathless storytelling), the young boy Orlando, an eager wannabe poet from an aristocratic family, has fallen into the favor of Queen Elizabeth I after presenting her with one of his rhymes. Soon after being made a royal mascot, Orlando shares an intimate moment with Her Majesty, during which she tells the fresh-as-milk youth, “Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old.” Thus, Potter establishes Orlando’s immortality as both mystical and a regal directive. The literalizing frame that it puts around the character’s journey to come is somewhat reminiscent of Albert Lewin’s 1945 adaptation of another cornerstone of queer literature, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, which invents a supernatural totem of an Egyptian black cat sculpture to give credence to Dorian’s “curse” of eternal youth. In this case, the Queen’s edict provides the film with a double helping of queerness: in a bit of gender-bending casting, the Queen is played, with delicious desiccation, by Quentin Crisp, the famed gay writer and raconteur, making his fairy-godmother blessing something like a queer decree. Here, as though with the wave of a wand, the Queen has bestowed life upon our hero, all but setting in motion the events that will eventually lead to him shirking the straitjacket of his male sex.

In this way, Orlando is also defined as unique to everyone else, more so than in Woolf’s book, which has various supporting characters emerging in and out of Orlando’s life over the course of many centuries as well, all of them subject to the same vicissitudes of time, the author’s true subject. Thus onscreen Orlando’s queerness—and eventual transformation at film’s midpoint into a woman—becomes something like a source of pride, which helps situate the film well and cleanly into the ethos of the New Queer Cinema. That political and aesthetically forward-thinking movement was partly defined by B. Ruby Rich this way: “In all of them, there are traces of appropriation, pastiche, and irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind. Definitely breaking with older humanist approaches and the films and tapes that accompanied identity politics these works are irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive. Above all, they’re full of pleasure.” All of this applies to Orlando the movie, which uses Woolf’s novel—itself full of pleasure, as well as irony and satire—as a springboard for an inquiry into the politics and standards of its own time, and toggles between narrative minimalism and visual excess.

It’s remarkable that Woolf’s book, written at an infinitely more repressive historical moment and in a country where homosexuality was outlawed, is as queer in its own way as Potter’s “gay nineties” film, in some ways even more so. Queerness is not just desire but also a hard-won stance against cultural and biological standards and practices, and Orlando, a proto-trans woman who literally exists outside of accepted notions of time, might be the queerest figure in all of fiction. Woolf is constantly teasing the reader with matter-of-fact moments of gender fluidity, including a noteworthy early instance when Orlando falls in love with a Russian visitor at first sight; despite the fact that “the loose tunic and trousers of the Russian fashion served to disguise the sex,” he cannot deny the “extraordinary seductiveness which issued from the whole person.” In Potter’s film, this person, who turns out to be the Russian ambassador’s daughter, is very clearly a woman—though Swinton playing the male Orlando undeniably mitigates this as a strictly hetero screen romance. The character’s inability to discern male from female in potential lovers—and the needlessness of ultimately doing so—is a recurring theme in Woolf’s book, most dramatically when it’s discovered that an acquaintance of Orlando’s, the Archduchess Harriet (likened to a giant hare in her gawky lankiness), is actually a man and had long been passing as a woman after seeing a portrait of Orlando and falling in love with him. In a sweet-natured Shakespearean twist, the Archduchess Harriet, or rather the Archduke Harry, no longer has to disguise himself once Orlando has himself become a woman.

Woolf’s description of Orlando’s transformation—which occurs following a wild celebration of his ambassadorship in Constantinople—is pragmatic, practically and strikingly modern: “Let biologists and psychologists determine. It is enough for us to state the simple fact: Orlando was a man until the age of thirty, when he became a woman and has remained so ever since.” Potter’s version of this turning point, which similarly disposes of any idea that this is some form of either spiritual or literal castration, is extraordinary in its own way. After the horror of witnessing firsthand war between the Turks and the invading enemy, and seeing a man die in front of her (“Not a man, he’s an enemy,” assures the Khan with whom he was trying to make political inroads), Orlando wakes up the next morning in his bed, now fully a woman. Perhaps she has renounced her sex after seeing the evil that men do; it’s left implicit. In close-up, Swinton splashes water on her face, dust sparkles all around her like crystals floating in the early morning sunlight. She turns before the mirror, full-frontal nude, exquisite, and in a dispassionate Woolf-like cadence, intones, “Same person, no difference at all—just a different sex.”

Orlando may indeed be the same person, and acknowledge herself as such, but in the eyes of larger society a woman is hardly treated the same. Now, in 1750, she experiences firsthand the brunt of male boorishness: the literary salons and circles she craves often devolve into self-satisfied witty men—including Pope, Addison, and Swift—making generalizations about the “fairer sex,” claiming that they reject the company of other women and are lost without the guidance of a father or husband. Swinton’s response is to look directly into the camera, wryly communing with the modern viewer while acknowledging that women often stayed silent during such humiliations. By the end Woolf does have Orlando get married, to an androgynous man who, it is discovered, had been a woman (it’s worth noting that Vita Sackville-West and her husband, Harold Nicolson, had an open marriage and both carried on same-sex relationships). Potter, however, leaves her unmarried, choosing sexual freedom, social independence, and single motherhood for her heroine.

Woolf’s concluding chapter is an extraordinary freeform dive into Orlando’s consciousness, after hundreds of years of mostly being kept outside of it. “The Oak Tree,” the epic poem that Orlando had been puzzling over for centuries has now, in the year 1928, been published. Experience and progress enable reflection and retrospection. Time collapses, and the various Orlandos, male, female, rich, poor, suddenly inhabit one space, one soul. Potter’s film also ends in the present day, but its own. In 1992, Orlando is still vibrant, perhaps more full of life than ever; she has a daughter and a motorcycle, she wears trousers, and she’s also a published author. She tells us in voiceover, “Ever since she let go of the past, she found her life was beginning.” It feels like a bit of a reversal of Woolf’s final passages, which insist that the past is always within us, informing us; but these concluding thoughts have their own purpose. A herald angel appears, captured in lo-fi video in one of Potter’s most brilliantly modern gambits. A tear falls down Orlando’s cheek. Perhaps if she’s through with the past, she has become mortal. Perhaps this figure, so long marked by sexual, social, and temporal queerness, is being admitted into the forward march of time. Welcome to the ’90s.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to the Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.