Private Property (1960)

Two scruffy drifters climb up a bluff on a stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway in the opening shot of Leslie Stevens’s Private Property. Where did they come from? Who knows. Behind them, their beach footprints lead straight into the ocean. All monsters should come crawling out of nowhere like Duke (Corey Allen) and Boots (Warren Oates), then stroll across the road and extort some orange pop and a pack of Viceroys from the first human they encounter—a gas station attendant who refuses to meet their eyes.

For the modern viewer, the opening has added resonance. Private Property has been unseen for decades. The AFI note for the film on Turner Classic Movies’ website states mournfully: “No print of this film could be located.” A few years ago that proved not to be true—elements for this film were rediscovered, exactly where I’ve been unable to divine—and it has been restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive, with funding from the Packard Humanities Institute. It screened last year at UCLA’s annual preservation festival, and TCM’s own Classic Film Festival will screen it next Friday. A Blu-ray release is planned for this summer by Cinelicious Pics.

The case of Private Property shows why vanishing acts aren’t just for silent movies. Shot in 1959, over five days, for just under $60,000, it focuses on how Duke and Boots stalk wealthy, beautiful housewife Ann (played by Kate Manx, the director’s wife). The aim is to use her to initiate Boots into the world of sex with women; he’s probably gay, a fact referred to casually and unmistakably. The two men follow her home, move into the empty house next door, and spend the vast majority of the film’s running time spying on her, trying to worm their way into her house, her swimming pool, her bed. Duke, a true sociopath who can fake sincerity with frightening ease, insinuates himself into Ann’s trust, and his task is made easier by Ann’s explicit sexual frustration with her career-obsessed (perhaps latently gay) husband Roger, played by Robert Ward.

Even as the ’60s dawned with the promise of smut on the horizon, this kind of thing wasn’t going to fly with the PCA, and it didn’t. The film had to be released without a seal, and it was condemned by the Legion of Decency. Helped by enthusiasm in Europe, the box-office take was still about $2 million, but without studio backing, and forced to screen well outside mainstream distribution, the movie had no place to call home.

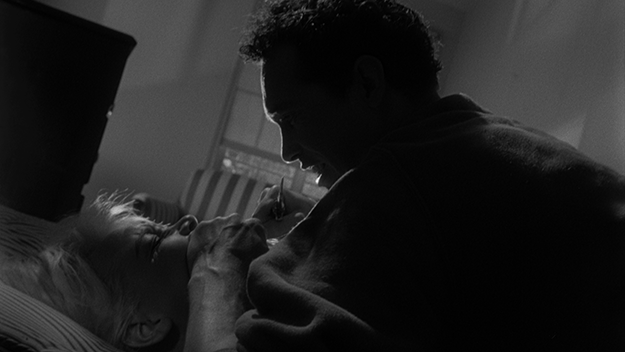

All this may make Private Property sound like a rough-hewn, indifferently shot quickie, but in fact the filmmaking has enormous panache. Leslie Stevens worked with Orson Welles at the Mercury Theatre, and he shared his former boss’s taste for elegant but unsettling framing. After meticulous storyboarding, to cut down on time and expense, it was filmed in and around Stevens’s actual Beverly Hills home, and the outdoor photography, via veteran DP Ted McCord and cameraman Conrad Hall, is suffused with heat and smog. Allen and Oates are repeatedly shown at windows, slavering at Manx in a way that feels like an assault. Late in the movie, as Duke comes closer to seducing Ann, he dances with her to an ersatz “Bolero” (the movie’s score is not its strong point) while they’re framed by a shady bower, as though Eve is tangoing with the Serpent.

When Duke pretends to be a landscaper in search of work (“Is this the Hitchcock residence?” he asks, in one of the film’s more obvious jokes), his wide-eyed innocence is belied by the way he keeps subtly invading Ann’s space, inching closer every chance he gets. Allen moves with whispery nastiness, his chief weapon a series of smiles so smug and vicious they border on nauseating. Oates, in contrast, plays Boots as an overgrown kid who looks at Ann like she’s a stuffed toy his father has promised to win at the fairground. Upon arrival at the empty house, Boots walks out of a room and announces: “He’s got a calendar in there.” “What day is it?” asks Duke. “It’s a broad in a cowboy hat,” comes the reply. It’s a classic psycho-and-lackey setup, with Duke using his more innocent comrade to amuse himself.

Manx’s performance hits a more basic series of notes, and many of them have to do with sex. She enacts a series of Freudian shots so blatant they evoke real pity for the character: caressing an ice cube with her lips, stroking a tall candle, applying perfume from a huge bottle with a stopper that looks more like a dildo than some dildos do. Andrew Sarris didn’t care for the movie or for Manx, denouncing the filmmaking’s “affected artiness” and adding that “all that lingers in the mind from Private Property is Stevens’ feel for feelthy fetishism and the hauntingly stupid blonde beauty of the late Kate Manx, Stevens’ wife and garish Galatea.” Our new chance to see the film shows Sarris’s judgment isn’t fair to Manx (who committed suicide in 1964, after splitting from Stevens) or the way her character is conceived. Ann tells Duke that she’s fired the maid, because there wasn’t enough work to make one necessary. Her husband’s frequent absences make cooking superfluous. They have a gardener, so Ann doesn’t need to tend the trees and the flowerbeds, and she has no neighbors to talk to. Her yearning for sex is part of wanting human contact, or anything that can make her life about more than sunbathing and changing outfits.

Private Property’s ability to shock has come and gone; there’s no gore, zero nudity, and no profanity either. (At one point Duke exclaims “What the flop?” in one of the more hilarious f-word euphemisms I’ve encountered.) But the slow, simmering dread remains. Duke and Boots make their way to Ann and Roger’s house by hitching a ride with Ed (Jerome Cowan), a sales manager for the Sacramento Appliance Company. Through a mix of guile and threats, they persuade him to follow Ann’s car. The shiny, contented Ed tries to explain to his passengers that Ann is not their kind: “These things are broken down into groups. You wouldn’t mate a bird with a snake . . . It just can’t happen.”

Duke’s reaction is as American as cherry pie; if he can’t have something, he will find a way to get it. In Private Property, our reticence about social divisions only makes them more poisonous. It’s hard to look at Duke and his follower Boots, prowling the margins of California wealth, without seeing an eerie premonition of Charles Manson nearly 10 years later. Duke and Boots stay camped out on the edge of prosperity, the unseen, festering discontent that the comfortable fear most.

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film on her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and recently published her first novel, Missing Reels. She is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.