Prince Among Men: Under the Cherry Moon

The first thing I thought of when I heard about Prince’s death was “Sometimes It Snows in April.” The song is one of my favorites, a ballad about a friend who died far too young, recorded on April 21, 1985, exactly 31 years before Prince himself died. When I started listening to Prince, the song realigned my whole perspective of him. He was clearly capable of great beauty, but I didn’t realize he could write something so moving, something that spoke with such depth. What I also didn’t realize when I first heard “Sometimes It Snows in April” were the origins of the album on which it appears: like Purple Rain, it was a soundtrack to a film starring Prince, but because the movie itself was so maligned it was largely forgotten. To me, Under the Cherry Moon (1986) represents Prince’s unconventional genius just as fully as that incredible song.

Like David Bowie, Prince seemed to be an artist made for the screen. As much of a virtuoso as he was musically, he clawed his way to success in makeup and thigh-high boots, cultivating a wholly unique aesthetic and persona. He had to be seen just as much as he had to be heard. Prince’s first film was a star vehicle that recast his Minneapolis underdog story as a glossy, musical soap opera. Purple Rain (1984) was a perfect film for Prince and a perfect film for its era, a crowd-pleasing, two-hour music video that channeled the electricity of his live performances directly into theaters.

After Purple Rain, Prince had essentially summited pop cultural Everest, becoming simultaneously responsible for the number one film, album, and single in the country for a number of weeks. Six years into his career, he had—by any conceivable definition of the phrase—made it. Warner Brothers had stumbled upon an incredible talent and hoped Prince could repeat his formula over and over for them. Prince had different ideas. A true believer in the myths of the ’60s counterculture, he seemed to think that, like the Beatles, commercial success would bring him artistic freedom. Around the World in a Day saw him dabble in psych pop and sing of fiery political indignation and religious salvation. He refused to tour for the album, or feature his image on the cover, or release any preceding singles or music videos.

Prince seemed determined to avoid making another Purple Rain. Under the Cherry Moon was the result of that determination, a film directed by and starring Prince—his ultimate vanity project. The story of a piano-playing con artist who falls in love on the French Riviera while trying to swindle an uptight young heiress, it was lambasted by critics and ignored by audiences.

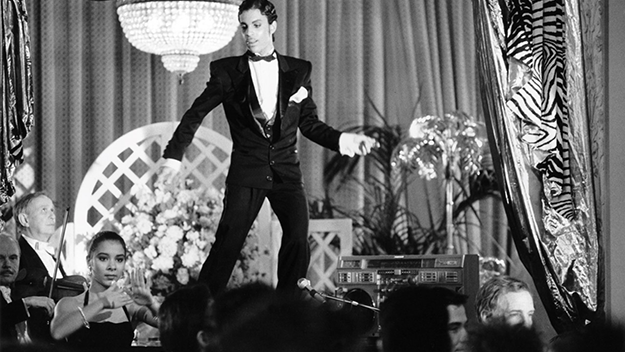

The flaws of Under the Cherry Moon are obvious. The story is cliché and plodding, and Prince and co-star Kristin Scott Thomas have little chemistry. Playing a smooth gigolo (“Christopher Tracy”) isn’t much of a leap for Prince, but the film makes obvious just how important the musical sequences were in Purple Rain, elevating Prince’s performance by putting his unparalleled stage presence and hyper-sexual cool front and center. There is only a single musical number in Under the Cherry Moon, a party-crashing performance of “Girls & Boys.” Forced to carry much of the film dramatically, Prince stumbles.

Still, the film’s broad comedy is absurd and charming, and reveals one more of Prince’s many natural gifts: his sense of humor. Blessed with impeccable timing and an elastic face made for mugging, Prince and his partner-in-crime Jerome Benton bounce off of each other like a comic duo who’ve been plying their act for years. See the classic “wrecka stow” scene, or any of the countless reaction GIFs the internet has pulled from the movie.

Under the Cherry Moon also couldn’t be faulted for its ambitions. Shot in black and white by Michael Ballhaus, cinematographer to both Fassbinder and Scorsese, the film is visually gorgeous, and there is a great deal of subtle subversion in the conflict between the crass and vibrant Christopher Tracy and the film’s thoroughly white, upper-class setting, or between Prince’s modernist, pop inclinations and the film’s reinterpretations of old Hollywood glamour and classic European filmmaking.

Parade, the stellar soundtrack album, in many ways says more about the film than the film ever says about itself. There is more life and joy conveyed in the album’s two-minute parade-march opener than by the thinly drawn Christopher Tracy character it’s named for. There is a thousand times more passion and heat in the tightly wound blues-funk of “Kiss” than in the cold, awkward make-out session with Kristin Scott Thomas that accompanies it in the film. There is such incredible, bittersweet emotion in “Sometimes It Snows in April,” a song written for a death scene so melodramatic that it likely inspired laughter from audiences.

What Parade makes obvious is that Under the Cherry Moon was no cash grab. Prince had a clear vision he was chasing, a stylish marrying of American and European sensibilities (Musically, the album combines the funk and rock of his earlier work with dance music and French chansons), a story and an album about the joy of being alive and in love, and the inevitability of both ending. It was a message Prince was far more adept at sending musically than cinematically, and the more one appreciates the album, the easier it is to recognize Under the Cherry Moon‘s ambitions through its flaws.

In the years that followed its release, Prince would go against the grain time and time again, inventing new personas, pursuing strange personal projects and triple albums. When he finally crafted a sequel to Purple Rain, the film, Graffiti Bridge (1990), was an even bigger failure than Under the Cherry Moon, as if he’d deliberately set out to prove how bad of an idea it was. By the mid-’90s, he was writing “SLAVE” on the side of his face and sabotaging his own career to pry himself away from his deal with Warner Brothers.

To anyone who’d followed his work closely, these actions made perfect sense. From the beginning, Prince had fought record labels and staked his independence, as if he were insulted by the idea that even a portion of his art could be owned by anyone else. Even his resistance to the Internet is understandable in retrospect: Prince couldn’t cooperate with a medium that required such a forfeiture of control to his audience. It was all his, and it was for himself much more than it was for the people wringing money out of it, or the critics analyzing it, or even the fans who enjoyed it. In an interview with The Wire in 1995, Brian Eno mused:

I’ve been thinking a lot about the kinds of artists who don’t censor their own work. I can think of three conspicuous ones: Picasso is one, Miles Davis is another, Prince is another. They’re all people who just put it out, and I think they have almost no critical self-censorship. They say, “Let the market decide; let the world decide.”

From the moment Prince first stepped out on stage in his underwear, or sang a pop song about incest, he made it obvious that he had no intention of holding anything back. He refused to be bound by distinctions of gender, sexuality, race or genre, or to be anyone but himself. Under the Cherry Moon, for all its flaws, is a sterling representation of everything I loved about him. It is, warts and all, quintessentially Prince. A clever, stupid, indulgent, transcendent mess of personal interests, produced with no regard to anyone else’s expectations, unleashed on the world with nothing but cool, collected confidence. Prince was the very definition of an artist, endlessly, stubbornly determined to fly past our opinions of him and follow his own path, wherever it took him.

Under the Cherry Moon screens May 6 and 7 at IFC Center.