Present Tense: Used Cars

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

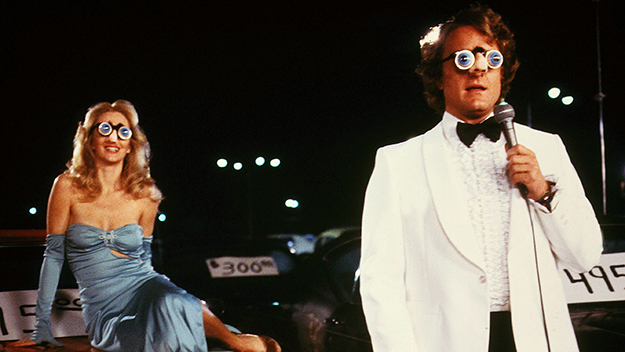

Deborah Harmon and Kurt Russell in Used Cars (Robert Zemeckis, 1980)

“This country’s going to the dogs. It used to be when you bought a politician, that son-of-a-bitch stayed bought.”

–Roy L. Fuchs, used car salesman, Used Cars

The dead man sits upright behind the steering wheel of a 1959 Edsel. Pennies are taped over his eyes. Around his neck is a garlic wreath. His three employees stand in the pouring rain, arguing about what they are about to do, which is: push the Edsel—with the dead man in it—into a pit, fill in the pit with dirt, and then tell anyone who asks that the dead man is on vacation in Miami Beach. The three employees have not murdered this man. He died of a heart attack. They are not guilty of anything. It’s just that it would be in their best interests financially to have the man “out of town” for a while. As Kurt Russell says in the commentary track for 1980’s Used Cars: “It takes a certain audience, from this point on.”

It still takes a certain audience. Used Cars, co-written by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, and directed by Zemeckis, was released in 1980 (barely), by Columbia Pictures, who didn’t seem to know what to do with it. Despite the presence of Stephen Spielberg and John Milius as executive producers (they had given Zemeckis and Gale the idea for the story), the marketing campaign was a mess. The film previewed strongly, but even with a couple of good reviews (including Pauline Kael’s memorable piece in The New Yorker), Used Cars flopped. Maybe the timing was off. Airplane! had just opened, and was a massive hit. Used Cars may have seemed, on the face of it, to be an Airplane!-type comedy, but it really isn’t, and so the film was unable to piggyback on the success of the other. Meatballs and Animal House had ushered in a new “gross-out comedy” craze, but Used Cars isn’t that either. Used Cars is for grownups, not adolescents. It’s also one of the most cynical American movies ever made, and certainly the most cynical comedy. As Robert Zemeckis once stated, “Rudy Russo is Jimmy Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life, except that he’s totally corrupt. This movie is structured like a classic Frank Capra movie, except that everybody lies.” There’s your poster tag-line.

Rudy Russo (Kurt Russell) is a used-car salesman in Mesa, Arizona. He is first seen—in the show-stopping opening shot—turning back the odometer of a car from 98,000 miles to 30,000 miles. As we will see, this is the least of his crimes. The dusty lot where Rudy works is owned by Luke Fuchs (Jack Warden), an old geezer with a bad heart. He could “go” at any second. Across the highway is another used car joint, run by Roy Fuchs, Luke’s twin brother (also played by Warden). Roy’s lot is about to be razed to the ground to make room for a highway overpass, and Roy wants Luke’s lot, but Luke won’t sell. Roy begins a campaign to drive his brother into an early grave. Meanwhile, Rudy has his sights set on a career in politics, purely because of the graft possibilities. His campaign slogan is “Trust Me.” Luke has promised to stake Rudy the $10,000 Rudy needs in order to buy himself a Senate seat, but Luke drops dead of a heart attack (in one of the funniest scenes in the film). Rudy then convinces fellow salesman Jeff (Gerrit Graham), so superstitious he is never without his rabbit’s foot, and mechanic Jim (Frank McRae), who falls asleep holding lit blowtorches, to bury Luke in the Edsel, and conceal the death until the money comes through. Rudy believes in the American Dream, and believes he—in his plaid jackets, tight pants, wide ties, and nonstop lying patter—is the embodiment of it. Who’s gonna tell him he’s wrong?

Every scene in Used Cars includes compounding objectives and obstacles. Nothing goes smoothly. Everyone’s working competing angles. Even Luke’s dog is a con artist. Hungry for television time, but not wanting to pay for it, Rudy hires a couple of AV nerds (Michael McKean and David L. Lander—Lenny and Squiggy together again) to pre-empt broadcasts of first a football game and then President Carter’s televised address, with wildly inappropriate “commercials” for the lot, broadcast live. Later, being interviewed by the local news station “KFUK,” Jeff denies he was behind pre-empting the President, sneering, “Do you think we like being associated with the President of the United States? We run an honest business here.”

The sudden appearance of Luke’s estranged daughter Barbara Jane (Deborah Harmon) throws a wrench into their plans. She has no idea her father is currently sitting dead in a car 6 feet under with pennies on his eyes. To throw her off the scent, Rudy takes her out to romance her. It works, kind of. He actually starts to have feelings for her (it is a testament to Kurt Russell’s talent that you believe this.) When Barbara Jane inherits the lot, she instantly gets in trouble for false advertising, and Rudy races to the rescue. The rescue involves roping in hundreds of teenagers to drive 250 beat-up cars across the desert, for reasons too complicated to go into. The sequence is a stirring and ludicrous masterpiece, with Kurt Russell standing in the back of a pickup truck beside Harmon, calling out directions to the drivers through a bullhorn, all as patriotic music swells. It calls to mind the cattle drive in Red River, the chariot race in Ben Hur, the final sequence in any sports movie, except it’s all in service of a giant con. The final shot of Used Cars shows Barbara Ann conning a sweet little old lady into buying a bucket of bolts, all as Rudy beams with love and pride. The corruption is complete.

Kurt Russell was known mostly for Disney movies at this point. The year before, he had played Elvis in John Carpenter’s heartfelt made-for-TV movie, the beginning of the sea-change in Russell’s career, his transition from teenager star to adult star. But nothing he had done could prepare you for Rudy Russo, who is anti-Disney to his bone marrow, a sweet-talking cockily-grinning motormouth, a gleefully venal grifter, who doesn’t lose in the end, but triumphs, amorality intact. The next year, Russell would do Escape from New York, the real game-changer, but Rudy Russo helped pave the way.

What is most shocking about Used Cars is how it does not pull one punch. With subject matter this cynical, you can usually clock the moment a film loses its nerve. The third act cops out, betraying the first. The anti-hero is forced to learn/grow/change, by loving a good woman/taking care of a child/developing a functioning moral compass. The audience is reassured the world isn’t that bad a place after all. Not only does Used Cars resist, it doesn’t even seem tempted. It’s as hard-hitting as a serious “message” drama (harder, really), and also much much angrier. But Used Cars is also a comedy, a live-action-Mad-Magazine-cartoon with a sight gag every 20 seconds. Maybe because of this, Used Cars feels legitimately dangerous. All good satire is dangerous. People still get freaked out by A Modest Proposal, and it was written almost 300 years ago. It takes a lot of nerve to make a movie like Used Cars.

Zemeckis and Gale’s first film as a team was I Wanna Hold Your Hand, an affectionate and funny ode to Beatle-mania. They were rowdy up-and-comers, writing the screenplay for Spielberg’s 1941, produced by Milius. Spielberg was instrumental in getting Used Cars made, securing financing through Columbia and serving as executive producer, alongside Milius. Budgeted at $8 million, Used Cars was shot in 28 days in Mesa, Arizona. There are hundreds of extras. Hundreds of cars. Huge explosions. Truly dangerous stunts. (The most hair-raising moment involves Gerrit Graham walking backwards on an empty road as a car barrels towards him.) A camera operator was almost killed. Everyone was doing copious amounts of cocaine. The film plays like a bat out of hell. It doesn’t seem possible that Used Cars was made by the same guy who made Forrest Gump. To quote Fred Willard in A Mighty Wind, “Wha happened??” Up until Flight, 32 years later, Used Cars was the only R-rated movie Zemeckis directed, and it earns that R the old-fashioned way, with gratuitous nudity and nonstop profanity, not to mention a profoundly anti-social attitude.

In Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart famously says, “Ilsa, I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.”

Rudy Russo would probably agree with this, but he wouldn’t go on and on about it. He’d just say: “Ilsa, I’m no good at being noble.”

Happy new year.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.