Present Tense: The Death Scene

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950)

Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950)

In the fifth episode of the celebrated 1976 mini-series I, Claudius, Augustus (Brian Blessed) has premonitions of his death. He begins to suspect he has been poisoned. (He’s right.) He refuses food touched by human hands, including his wife Livia, a sociopathic Siân Phillips. Finally, in one scene, Livia stands over his death bed, delivering a lengthy monologue. At first Blessed stares up at her, wide-eyed with horror. As she speaks, offscreen, the camera slowly zooms in on his face, and you watch the life drain out of his eyes. His mouth falls slack, and his face settles into the mask of death. And still Livia speaks. She speaks for an astounding four and a half minutes, and the camera never leaves Blessed’s face. It’s not a freeze-frame. Brian Blessed had to keep his face “dead” for four and a half minutes. It’s one of the most awe-inspiring technical feats I’ve ever seen in the “death scene” realm.

The challenges of death scenes are technical, for the most part, but there’s also an existential element. If the camera remains on you, you have to slow down and control your breathing so your chest doesn’t move. Dying with your eyes open presents other challenges. But the biggest challenge is the most obvious, and yet it’s rarely mentioned: death is the only universal experience, shared by all humans, where no one can report back what it feels like. There’s no intel for actors to draw upon. An actor only knows the visible results, but you can only guess at what it feels like to have your heart stop, life itself to cease. Even experiences shared by only a handful of people comparatively—like murdering someone, or blasting off into space in a rocket, or performing brain surgery—can be researched. The people who have done these things have told us what it’s like. Not so with death.

Brian Blessed said that director Herbert Wise came to him the morning of the day they shot the scene, telling him how they were going to do it. Blessed had no time to stress out about it, or even practice how he would do it. It was a feat never attempted before, but Blessed thought it would be worth it, saying, “We wanted to see the Roman Empire dying in that face.” It’s the kind of scene—a high watermark—that inspires awe in actors. His eyes don’t water; they remain in a fixed glassy stare. His face lies slack, his mouth slightly open, and there’s not one muscle twitch, not even the tiniest suggestion that life is left in him. Blessed said that as the scene went on, he went “into a kind of strange coma. You might say meditation but that would be the wrong word. It was such an ordeal. I started to not be aware of where I was. My brain stopped thinking.”

Once Upon a Time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984)

Janet Leigh faced a similar challenge when she lay dead on the shower floor in Psycho. Starting with an extreme close-up of her open and frozen eyeball, Alfred Hitchcock slowly moved the camera back, to reveal her face, water still dripping down her nose. There is one moment when there’s a tiny ripple in her throat, but it was the best take they got, and it’s extremely effective. Like Blessed, there’s a glassy quality to her eyes, the life has been yanked out of her body.

Child actors often toss themselves into death scenes with fearless gusto. I call this the “Bang Bang You’re Dead” School of Acting. Watch the swan dives of children playing cops and robbers in the backyard and you’ll see total commitment to the imaginary. In Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, one of the child gangsters in the opening sequence is gunned down in the middle of the street. Filmed in slo-mo, the child, shot in the back, falls to his knees, and crumples forward, his right leg splayed out to the side. His leg moves for a second before finally falling still. Part of the actors’ job is to stay close to a childhood mindset, where playing make believe is second nature. A child doesn’t have to think about how to pretend to pour a cup of tea when there is no tea pot, tea cup, or tea. They’re unselfconscious.

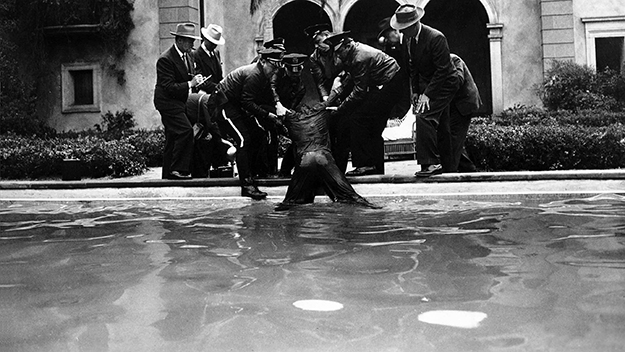

William Holden’s death scene in Sunset Boulevard is akin to the child’s death in Once Upon a Time in America, and required great athleticism, which Holden had in spades (director Billy Wilder said: “Physically, [Holden] was first-class.”) Watch that scene again. It’s done in one unbroken take. It’s all on Holden to create the throes of violent death, to move with it, to play out the different stages of it. He exits the house, holding a briefcase, and Gloria Swanson shoots him in the back. His body goes rigid, his back arched, his head flung back, and then he plunges over, dropping the briefcase. She shoots him again, this time in the side, and he crumples down further, staggering backwards to face her in shock. Disoriented, he leans forward to pick up his suitcase (maybe he thinks he can still make it out of there), and this is when she shoots him for the third and final time. His swoon backwards is practically balletic: his body whips around to face the pool, his feet snagging on the pool’s lip, and the force of the gunshot plunges him into the water in a belly-flopping free-fall. This is “Bang Bang You’re Dead” of the highest order. It’s childlike “make-believe” in its purest form.

Shirley Maclaine and Frank Sinatra in Some Came Running (Vincente Minnelli, 1958)

Different scenes require different things. Actors’ inventiveness with such scenes is always a pleasure. There’s Marlon Brando’s death in The Godfather, cavorting in the orchard with his grandson, his steps slowly becoming more laboring. When the heart attack comes, his body falls to the side so quickly the camera almost loses him for a second. Brando grabs a nearby vine, and for a moment his body hangs there, before he falls backwards into a heap. He quite literally “drops dead.”

Shirley MacLaine’s death scene in Some Came Running is so sudden she is literally ripped from life. It’s a shattering moment. (Frank Sinatra suggested the death to director Vincente Minnelli, predicting correctly that if you “let the kid die,” she’d be nominated for an Oscar). MacLaine’s dance training has always been indispensable to her acting, with her three-dimensional awareness of her body’s movements and shapes. When she is shot in Some Came Running, she literally tosses her body up into the air, and then forward, pushed by the imaginary bullet’s force. It’s an amazing piece of physical acting, as though a giant hand reached down and plucked the life out of her.

There’s Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in Bonnie and Clyde, their bodies flapping around like rag dolls in the rain of bullets. Meryl Streep’s Helen is found dead in Ironweed, and her face, white as a sheet, is crumpled against the floor. She’s been dead a long time. She appears so dead that she is not present at all. Streep has “left the building” because Helen is gone. Jensen Ackles, in the long-running series Supernatural, has been required to die many times in the 14 years of the series’ existence; the character is a genuine Lazarus. Many times he has had to die with his eyes open, and, like Brian Blessed in I, Claudius, you watch the life—the self—vanish from his eyes, slowly and in real time. Whatever tricks he uses as an actor, his skill is masterful. In the final scene of Season 9, he lies on his bed, dead. He’s a corpse. He’s been dead for hours. Similar, again, to the scene in I, Claudius, another character (Mark Sheppard) stands over him and talks to his corpse. The camera remains on Ackles, whose face no longer looks like his face now that he the actor has removed the life from it. His features are flattened, puffed out, his mouth relaxed to the point that it’s eerie. He is no longer there. Ackles strolls into that undiscovered country for all of us.

James Cagney and Gladys George in The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939)

Perhaps the best “die-er” of all is James Cagney. Like MacLaine, Cagney was a dancer who understood intuitively how his body moved through space, what shapes it made, how to execute a turn, a fall, a stagger. In his essay on James Cagney in Who the Hell’s in It: Conversations with Hollywood’s Legendary Actors, Peter Bogdanovich writes of an audience Q&A with Cagney:

“One of the guests asked [Cagney] how he had developed his habit of physically drawn-out death scenes, probably the best coming at the conclusion of The Roaring Twenties, where he runs (in one long continuous shot) along an entire city block, and halfway up, then halfway down, the stairs in front of a church before finally sprawling dead onto them. In answer, Cagney described a Frank Buck documentary he’d once seen, in which the hunter was forced to kill a giant gorilla. The animal died in a slow, “amazed way,” Cagney said, which gave him the inspiration, and which he played out for us in a few riveting moments of mime.”

Actors are the ultimate observers, and everything—even a nature documentary—is potentially of use. This kind of approach can become too intellectual or belabored in the wrong hands, as though the actor wants to show all his work. But Cagney’s natural genius and physical ability results in a miracle.

The last scene of The Roaring Twenties flows with the freedom with his movement, his beautiful stagger first up and then down the church steps, his fearlessness coming from deep self-knowledge of what his body can do. But if you watch the scene again, you can also see a strange sense of amazement in him, his “slow amazed” response to dying. You can almost see him thinking: “I’m dying. Ain’t it somethin’? So this is what it’s like. Who the hell knew.”

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.