Present Tense: Out of the Blue

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

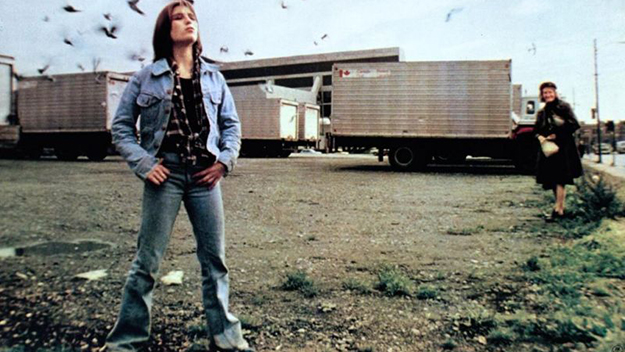

All images from Out of the Blue (Dennis Hopper, 1980)

“[It’s] the cage of life itself and all the anguish to break through which sometimes translates as flash or something equally petty but in any case is rock ’n’ roll’s burning marrow.”

—Lester Bangs, “The Clash,” New Musical Express, 1977

While there have been a number of great movies about punk rock—Jubilee, Rock ’n’ Roll High School, the mighty The Decline of Western Civilization—Dennis Hopper’s 1980 film Out of the Blue, about a punk-obsessed teenage girl, stands alone. The film emanates a kind of lurid clarity, doom-ridden, death-stalked. Out of the Blue is as shocking to watch today as it probably was in 1983 during its (very) limited and long-delayed release. The film isn’t about punk rock. It doesn’t have enough distance from the subject to be “about” it. Out of the Blue howls from the center of the whirlwind. Up through its violent and inevitable ending, the film takes punk rock at its word.

If punk rockers were “anti” everything, then what were they “for”? Rock critic Lester Bangs worried obsessively over this question, as was his wont, in his essay about hanging out with The Clash. He perceived the rage in the music, but he also saw how sweet and generous the band was to their fans. Bangs felt The Clash were “the model of a truly egalitarian society.” There was a sense that they all were in this together, whatever “it” was. The institutions of a post-industrial civilization were rotten to the core. Tear it all down. What might be built afterward was somebody else’s problem.

Out of the Blue, an incandescently angry film, doesn’t care about building something, either. CeBe (Linda Manz) and her mother Kathy (Sharon Farrell) have a rocky relationship. Kathy is far too busy with her waitressing job and heroin addiction to parent her “difficult” kid. According to Kathy, CeBe is never going to attract a man, looking the way she does. Six or seven years before, seen in terrible flashback, CeBe’s father, Don (Hopper), crashed his truck into a school bus, killing a bunch of kids. CeBe had been in the passenger seat, and Don was drunk, focusing more on flirting with her, kissing her on the mouth at one point, than keeping his eye on the road. The child revels in his attention, but an abyss opens up with that flashback, one which never closes. There’s something nasty here, rank and vile. Years later, Don is about to be paroled. CeBe barely remembers him, but he looms large in her memory.

CeBe is an androgynous loner, decked out in a denim jacket with “ELVIS” bedazzled on the back. Her room is a shrine to The King. She loves punk rock, too. But her heroes are gone. Elvis died in 1977 and Sid Vicious in 1979. She sings “Heartbreak Hotel” to herself, scuffing along the sidewalk, flicking her cigarette into a puddle. In one scene, she carves a grim swath across a field at school, through the football players and cheerleaders, and she is a truly punk-rock figure, contemptuous and “anti” all of it. CeBe says to her mother, in a tone devoid of self-pity, “Elvis died on me. So I’m gonna kill myself so I can go visit him.” Raymond Burr plays a psychologist trying to understand the family. Kathy lies to him, playing “concerned” mother, and CeBe, bored, messes around with the toys on his desk, barking at him, “Don’t listen to her.” Don’s return home is nasty. He makes a drunken scene at his welcome home party. He’s unrepentant about his crime. CeBe hangs onto her fantasy of him. Except for Elvis, it’s really all she has.

As CeBe, Linda Manz gives one of the great teenage performances of all time, and this on the heels of her performance in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven the previous year, where her voiceover narration—improvised by Manz as she watched the footage—is so crucial it’s impossible to imagine the film without it. Manz has a tough and knowing presence, a scrappy street urchin with a New York accent straight out of a ’30s gangster movie or Mean Streets. She is in the glittering pantheon of 1970s tomboy teenagers (an archetype I love and miss). Manz seems completely un-studied, unable to lie or fake it. Her face when she looks through the glass at her father during visiting day at the prison is so fragile and open you want to weep for her, even though you know CeBe would probably scream “DISCO SUCKS!” at you if you dared cry for her.

In a central sequence, CeBe hitchhikes into the city to seek out the local punk scene. She walks along the side of a highway, thumb jutted out, “ELVIS” a shield on her back, screaming epithets at cars that pass her by. She seems indomitable. In one of the film’s only joyous scenes, she goes to a club, and is invited onstage by the Pointed Sticks, a Vancouver punk band, who let her drum during one of the songs. The sight of CeBe, smashing those sticks around, shy and thrilled, is not triumphant, it can’t be, not in this film. But her emotion is piercing. She’s finally entered her dream.

Hopper, deep into one of his many Hollywood exiles, had been hired to act in Out of the Blue, a Canadian production filmed in Vancouver. After two weeks, the director (Leonard Yakir) was fired and Hopper took over, re-writing much of the script (by Yakir and Brenda Nielson) and re-structuring the narrative. Hopper hadn’t directed since 1971, when The Last Movie burned up the goodwill he had accrued with the surprise success of Easy Rider in 1969. Clearly Hopper wasn’t thinking “comeback” because Out of the Blue doesn’t have a commercial bone in its body. Producers recoiled from it. Roger Ebert went to bat for it, as did Vincent Canby and a few others, but they were outliers. The film vanished without a trace, although it lived vividly in the minds of those who saw it.

Hopper’s performance as Don was given in extremis—his mania and addictions are often apparent—but it is a harrowing piece of work. His eyes are gigantic and so haunted they seem frozen. Something’s not right, something human is not in operation. Hopper does not shy away from Don’s evil or try to explain him. The film assaults you with scene after scene showing that men are not to be trusted, particularly not with teenage girls, or girls of any kind. It’s relentless. CeBe has done what she could to survive having a father like Don, including recasting him as a rock ’n’ roll idol. Along with the Elvis collage in her room, she has a picture of Don, in black motorcycle jacket and hat, just like Marlon Brando in The Wild One, or like Elvis in his 1968 “comeback special.” Sexy rebel icons. As CeBe’s life breaks down, she realizes the only way “out of the blue” is—as “Hey Hey, My My”, the Neil Young song that gives the film its title says—into the black.

“Hey Hey, My My” plays throughout, giving this raw film a mournful elegiac mood. Young knows where all of this is going. The song’s valedictory line “Rock and roll is here to stay” leads to “It’s better to burn out / Than to fade away” (which Kurt Cobain quoted at the close of his suicide note). In Hopper’s fever-dream, Elvis–Sid Vicious–Neil Young are part of the same continuum. (He should know, he met and partied with them all.) By the time punk rock arrived, Elvis was seen as passé, square, wearing capes and doing karate moves for middle-class audiences. His days of being filmed from the waist up on the Ed Sullivan Show were long gone. But CeBe (and Hopper) loop together these disparate eras, perceiving it all as coming from the same outlaw place.

Lester Bangs gets at this in a rambling essay called “Notes on Peter Guralnick’s Lost Highway” where he makes the stunning claim: “In terms of sheer offensiveness and bizarritude, [Elvis] was way hepper singing things like ‘Do the Clam.’ I mean, that ranks right up there with Sid Vicious’s version of ‘My Way.’ Well, actually, you can’t play it as often but it sorta comes from the same place: nowhere. But nowhere is unassailable. Nowhere is Zen.”

Dennis Hopper straddled so many different eras, incorporating some things, throwing others out. Where there was so-called unity, he perceived contradictions, or the uneasiness of certain alliances. He saw the potential of an Altamont in Woodstock before Altamont or Woodstock even happened. He wasn’t a “joiner.” His acting training was old-fashioned, until he was radicalized by James Dean. His work with Lee Strasberg grounded him. (I took an acting workshop with him at The Actors Studio in the late ’90s; he was an extraordinary teacher, brilliant on sensory work and Strasberg’s “song and dance” exercise.) His rebirth in the mid-’80s was nothing short of a miracle, considering his years in the metaphorical wilderness. In a single year he appeared in River’s Edge, Blue Velvet, and Hoosiers (for which he was nominated for an Oscar). Each performance was unpredictable and risky, as well as highly skilled, and his Frank Booth, of course, is one for the ages.

It wouldn’t be accurate to say that Dennis Hopper built bridges, although his career often did just that. But he did exist in the tension where a bridge should be, that space in-between fraught with duality. The duality feels conscious and deliberate in him: balancing darkness and light, love and hate, sanity and insanity, creation and destruction. As Howard Hampton wrote in the May/June 2013 issue of Film Comment, Hopper had a “capacity for channeling instinctual contrariness into a gelatinous web of performance and detachment.” Hopper’s “instinctual contraries” gave him an inherently abstract point of view. In the 1971 documentary American Dreamer, he says to director Lawrence Schiller, “If this is going to be a documentary or a lifestyle film or whatever you want to call it, then it should expose . . . That’s why at the same time it’s a destructive act, it’s also a creative act for me. It’s a creative act to say, ‘Hey, I’m not gonna hide in the closet anymore. I am going to be at least a witness to myself, if nothing else.’”

Out of the Blue is not a forgotten film, but it is difficult to see, unless a festival programs it somewhere. As I was working on this essay, I stumbled across a Kickstarter page raising money for a 4K digital restoration for the film’s 40th anniversary next year. Our culture rarely welcomes a vision as nihilistic as Out of the Blue. But the film has a tremendous and frightening power. The most punk rock thing about it is that it stares “into the black”—and it doesn’t blink.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.