Present Tense: Infinite Brando

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

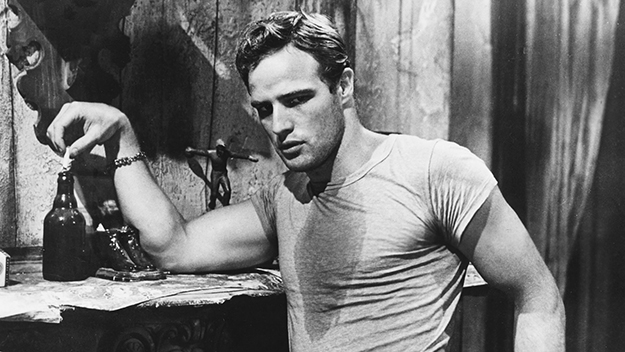

A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951)

“Jim, Marlon Brando was the archetypal new-type actor who ruined it looks like two whole generations’ relations with their own bodies and the everyday objects and bodies around them.”

So slurs the drunken James O. Incandenza Sr. to his 10-year-old son Jim in a sodden monologue 157 pages into David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel Infinite Jest. Incandenza Sr. is a bitter alcoholic, whose early promise as a tennis player was shattered by a knee injury. He is fearful his tombstone will read “HERE LIES A PROMISING OLD MAN.” After tennis came years as a struggling actor, a struggle which intensified after Brando swaggered onto the scene. (To Incandenza Sr. everything is “pre” or “post” Brando.) Seemingly overnight, Incandenza Sr. became “a disrespected and largely unemployable actor” with a “bitterness of ambiguous origin but consuming intensity toward the Method school of professional acting and its more promising exponents.” Jim Jr., suffering through his father’s lecture, eventually grows up to become 1) an experimental filmmaker and 2) founder of the Enfield Tennis Academy, before committing suicide via microwave oven.

Just like the play that gives the book its title, Infinite Jest is haunted by the ghosts of fathers. Incandenza Sr. is long dead by the time this 980-page tour de force (with 100 pages of footnotes) starts. The central character (if you can call him that) is Hal Incandenza, grandson of the “promising old man,” and son of the filmmaker/microwave-suicide. Hal is a tennis prodigy and budding drug addict. In this “flashback” (taking place in 1960), Incandenza Sr. comes to us in an unfiltered Molly Bloom–esque monologue about tennis, Method acting, Marlon Brando, and bodies. In his meandering, sloshed way, Sr. tries to impart to Jr. the advice denied to him by his own father: “Son, you’re a body, son… Commit this to memory. Head is body…” The launchpad for this monologue is a two-page rant on Marlon Brando’s acting. While so much of Infinite Jest is comedic (often outrageously so), there’s also much truth to be found in Incandenza’s bitter pronouncements about Brando. It’s an example of a writer strolling into an extremely crowded field—a field populated with critics and academics and film scholars—and cutting through all the white noise. It may seem silly, but this section in Infinite Jest helped me see Brando anew, and I’ve been studying him for years.

Marlon Brando to actors is like James Joyce to Irish literature: a giant on the shared landscape, one that can’t be destroyed, ignored, or avoided. Pretending it doesn’t exist means you’re still, on some level, acknowledging it. As Dan Callahan wrote in The Art of American Screen Acting, “[Brando] is a figure who still inspires awe and trembling.” You can see this most clearly in acting classes, watching young men attempt to play Stanley Kowalski, and it’s 2019, but they’re still wrestling to vanquish the ghost of Brando. Wallace’s observations about Brando’s relationship to the physical world adds a crucial piece to the puzzle, cutting through the vague bromides about “genius.” So much of Brando’s genius was physical and David Foster Wallace understood that.

If you listen to people talk about Brando’s early days as an actor, so many of them talk about his body: the primary impression he made was not emotional but physical. (His otherworldly beauty didn’t hurt.) This may sound so elementary, but we—the general “we”—are cut off from our bodies, and most of us don’t follow through on the gestures we want to make. Expressing ourselves fully would be too embarrassing or exposing. Self-consciousness is death to good acting, whether it’s how you enter a room, how you use your voice, how you reach for the bottle over the bar. Gestures are what make emotion and character objective and the story itself visible. Brando was particularly eloquent—even poetic—with his gestures. Think of the contemplative way he picks up Eva Marie Saint’s glove in On the Waterfront. Think of how he slides it on his hand. It’s not “just” a gesture. It ends up being more important than the words being said.

Eva Marie Saint and Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954)

Although Brando is often associated with “Method acting,” and “the Actors Studio,” the reality is more complex. He studied first with Stella Adler, who was known for encouraging actors to do research and use their imaginations (as opposed to Lee Strasberg’s focus on emotional memory). When Brando praised Stella for teaching him everything about acting, she retorted she had taught him nothing, adding that sending Brando to acting class was like sending a tiger to jungle school. “The body” was his “way in” to the fictional reality of a role. Boxing backstage during rehearsals for Streetcar Named Desire would get him “out of his head” and “into” Stanley, a character Brando described, unsurprisingly, in purely physical terms: “One of those guys who work hard and have lots of flesh with nothing supple about them. They never open their fists, really. They grip a cup like an animal would wrap a paw around it. They’re so muscle-bound they can hardly talk.” There’s a revealing anecdote about a moment during a rehearsal for Truckline Cafe in 1946, directed by Harold Clurman (Adler’s husband). Rehearsals were not going well. Brando had a big important monologue, and he couldn’t commit to it, he mumbled inaudibly, he was shy. Clurman stopped rehearsal and ordered Brando to climb up one of the ropes hanging from a gridiron on the side of the stage, all while shouting the monologue. Brando hauled himself up, hand over hand, screaming the lines in a frenzy, launched into the headspace of the character by his body’s exertions. When they ran the scene afterward normally, Brando’s performance was “there.” This is a somewhat mysterious process to people who’ve never taken an acting class, but actors will probably nod their heads in recognition.

As Brando started getting roles in New York, first impressions poured in of this new and exciting creature. Robert Lewis, one of the founders of the Actors Studio (whom Brando also studied with), recalled going to see I Remember Mama premiere on Broadway in 1944, and watching Brando “wander downstage munching an apple. He was so natural I thought he really did live upstairs. He just stood there and said nothing for two minutes, but the way he listened, you could not take your eyes off him.” There’s Pauline Kael’s famous recollection of going to see Truckline Cafe on Broadway in 1946: “I looked up and saw what I thought was an actor having a seizure onstage. Embarrassed for him, I lowered my eyes, and it wasn’t until the young man who’d brought me grabbed my arm and said, ‘Watch this guy!’ that I realized he was acting.”

In Infinite Jest, Incandenza Sr. bemoans the “new archetypal tough-guy rebel and slob type,” but as the monologue goes on, you hear his admiration for “the gentle and cunning economy behind this man’s quote harsh sloppy unstudied approach to objects.” I am dismayed when people don’t perceive the “economy” of Brando’s work. He didn’t just slobber around, “feeling” things all over the place. That’s an incorrect characterization of so-called “Method acting,” and it’s a category error in particular with Brando. Brando prepared. Brando had very good technique. When Brando was at his best, everything was in proportion. You don’t sense effort. Most crucially, Brando underlined nothing. His instincts led him into opposition. This wasn’t just bratty anti-authoritarianism. This was actor-as-tuning-fork to his own sense of truth. A conventional actor might shout an angry line. Brando would whisper it, turning the scene on its ear.

The best example of this is the anecdote about filming the famous taxicab scene in On the Waterfront. Brando didn’t like how it was written, he thought there was something phony about it. Director Elia Kazan trusted Brando and asked him to improvise the scene. The result is what ended up in the film. As Kazan marveled in his memoir: “What other actor, when his brother draws a pistol to force him to do something shameful, would put his hand on the gun and push it away with the gentleness of a caress? Who else could read ‘Oh, Charlie’ in a tone of reproach that is so loving and so melancholy and suggests that terrific depth of pain? I didn’t direct that; Marlon showed me, as he often did, how the scene should be performed.” As Incandenza Sr. moans in Infinite Jest, “You’ll know Brando when you watch him, and you’ll have learned to fear him. Brando, Jim, Jesus, B-r-a-n-d-o.”

Mary Murphy and Marlon Brando in The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953)

Incandenza continues: “He knew what the Beats know and what the great tennis player knows, son: learn to do nothing, with your whole head and body, and everything will be done by what’s around you.” This calls to mind Brando’s performance as Johnny, leader of the motorcycle gang in 1953’s The Wild One, where he is a pure spectacle in his black leather jacket, biker’s cap, rolled-up jeans, and motorcycle boots. The impression Brando makes today in The Wild One—even after decades of assessment and commentary—is still so electric you can feel the molecules dispersing in alarm as he walks down the sidewalk.

At one point, Brando follows the waitress (Mary Murphy) into the empty coffee shop. As Brando approaches her, he touches each chair lined up along the counter, setting them swiveling one by one. You can imagine James O. Incandenza Sr.’s swoon of outrage/envy watching this. Everything is of use to an actor as relaxed as Brando. The effect is that, as he moves towards her, there’s a wake of movement behind him, empty chairs swiveling, the entire coffee shop put into a state of flux. “Marlon Brando felt himself as body so keenly he’d no need for manner,” Incandenza observes. “In his quote careless way he actually really touched whatever he touched as if it were part of him. Of his own body. The world he only seemed to manhandle was for him sentient, feeling.” Those chairs are sentient, because they have been handled by him.

A couple of moments later, after ordering a beer, Brando places a coin on the counter, and there’s something almost delicate in the gesture, in the placement of his fingers. She reaches for the coin and he slides it out of the way. Teasing her. Making her work for it. A potentially banal moment ignites. The coin is now sentient, too, because he has touched it.

It’s not just Brando who is alive and unpredictable. He makes the world around him unpredictable. He activates the inner life of objects. This was an aspect of Brando’s work I had sensed, but Incandenza’s rant in Infinite Jest gave me the elusive “a-ha” moment. Incandenza’s whole sorry life—pursuing acting and tennis—has been about “the religion of the physical.” One can fake emotions, but the physical can’t be faked. Incandenza: “Jim, he moved like a careless fingerling, one big muscle, muscularly naive, but always, notice, a fingerling at the center of a clear current. That kind of animal grace. The bastard wasted no motion, is what made it art.”

In the libraries of commentary on Marlon Brando, no one has said it better.

Brando, Jesus, B-r-a-n-d-o.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.