Planting Seeds: Jeonju 2023

This article appeared in the May 11, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

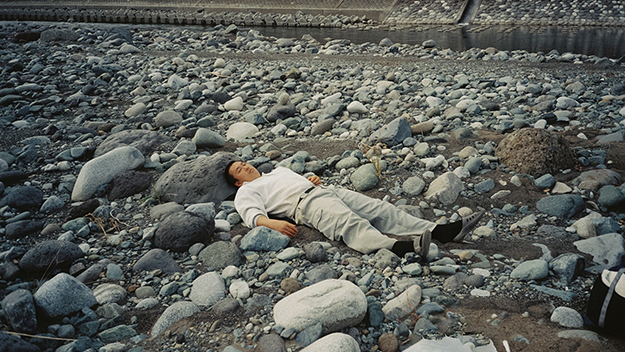

There Is a Stone (Tatsunari Ota, 2023)

Nine years ago this month, the Jeonju International Film Festival relaunched the Jeonju Cinema Project. Initially founded in 2000 to fund the production of digital short films by well-known directors (under the name Jeonju Digital Project), the rechristened and rejiggered program has spent the past decade producing three to five features per year by less established talent, shepherding each project from initial investment stages to distribution. As one of the foremost proponents of the increasingly crucial notion of the film festival as producer, Jeonju has, through this influential industry initiative, played an active role in amplifying new voices in contemporary art cinema. Past participants include Damien Manivel, Ted Fendt, and Dane Komljen, to name but a few.

In the introduction to a new monograph commemorating the 10th edition of the program, Jeonju programmer Sung Moon describes the JCP as “a safe zone for creators . . . [that is] free from all restrictions, including the cost-benefit ratio.” This freedom has resulted in a string of adventurous international productions, as well as a number of well-crafted, commercially minded Korean projects. The trend continued at this year’s festival as a pair of relatively straightforward homegrown documentaries—Lee Chang-jae’s This Is the President, a post-administrative portrait of South Korea’s former leader Moon Jae-in; and Jéro Yun’s Breath, an intimate investigation of death and its aftereffects—shared space with Lois Patiño’s Samsara, a tripartite gloss on reincarnation that was one of the more divisive films of this year’s Berlinale. While Samsara’s two bookending sections, set in the Buddhist temples of Laos and the seaweed farms of Zanzibar, respectively, have prompted accusations of tourism (Patiño is Galician), seemingly everyone agrees that its middle third, an interactive trip through the bardo, stands as one of the more extraordinary feats of expanded cinema in recent memory.

As attuned to the past as it is to the present (and the future), Jeonju added a section to its retrospective program this year—which otherwise focused mainly on former JCP productions—highlighting the work of film archivists and related figures working in the worlds of restoration and preservation. The subject of this inaugural sidebar was Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, who curated and presented a selection of HFA restorations, including what for me was the revelation of the festival: Ed Pincus’s 1980 first-person documentary Diaries (1971-1976). Conceived as both a recapitulation of the direct-cinema aesthetics of the 1960s and an interrogation of the feminist slogan “the personal is political,” Diaries comprises Pincus’s startlingly intimate 16mm footage of his wife, Jane (co-author of the landmark women’s health book Our Bodies, Ourselves); their two kids; and several women with whom the director was romantically involved. Pincus, who died in 2013, shot Diaries almost entirely himself, and thus is seen mainly in bathroom mirrors or the odd reflection. Speaking off-screen, he becomes a kind of invisible force in the film’s unfolding domestic drama, which centers largely on Jane’s struggles with the couple’s open relationship, their itinerant lifestyle, and, by the end, a mentally unstable former collaborator of Pincus’s named Dennis Sweeney, whose threats forced the family to relocate to Vermont. (In 1980, Sweeney shot and killed former U.S. Representative Allard Lowenstein.) At once a scathingly self-reflexive memoir and an uncommonly lyrical family portrait, Diaries also serves, with the benefit of hindsight, as an illuminating document of a very specific generation of white, middle-class liberals transitioning uneasily from disillusioned hippies to semi-well-adjusted suburbanites whose sociopolitical anxieties would take new forms in the 1980s.

Among the new films screened at the festival, the strongest I saw in both the Korean and International Competitions were, in fact, the winners of the top prizes in both sections. In Shin Dong-min’s Korean Competition entry, From You, a trio of stories—centered, respectively, on an unsatisfied fashion student, an actress trying to emotionally connect with an alcoholic parent, and a mother and son traveling to the former’s hometown—take shape in discrete movements that slowly evolve, refract, and speak to each other through subliminal storytelling echoes. With its rigorous black-and-white imagery, Hongian narrative recurrences, and casual breaches in character (Shin and his real-life mother feature in the film’s third section, and at one point enter a cinema as a director and actress to participate in an onstage Q&A about a movie very similar to the one we’re watching), From You is certainly of a piece with much of the most lauded recent Korean cinema, but it offers enough surprises and personal touches to differentiate itself amongst a crowded field.

If the International Competition winner, There Is a Stone, surprises, it does so through sheer modesty, welcoming the viewer into its world of small-scale human interaction quietly, almost incidentally. That it flew under the radar of most critics at the Berlinale is unsurprising. The second feature by Japanese director Tatsunari Ota, the film opens with a young female travel agent, Yoshikawa (An Ogawa), wandering the hills of an unnamed country town. Apparently doing research for a new tourism project, Yoshikawa occasionally asks around for interesting places to see or visit, but mostly finds herself walking alone through unpopulated areas far from the town’s suburban center. Eventually she meets Doi (Tsuchi Kano), an odd, childlike man skipping stones by a riverbed. At first suspicious, Yoshikawa is quickly drawn into Doi’s wide-eyed world of games and naive chitchat. After some time, they split up, only to reconnect later in the day. At night they go their separate ways, and in the morning, Yoshikawa departs by train, catching a glimpse of Doi from the window as he sifts through the river for the perfect stone. While it wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate to say that nothing happens in There Is a Stone, it would, contrary to the spirit of the film, be unimaginative. This is a movie that turns nonevents into moments pregnant with meaning and suggestion. Open and tactile, it calls upon nature and the most basic of human activities to perform the aesthetic and storytelling tasks that a more self-serious work would bypass in favor of metaphor, or employ as stylistic shorthand. Sometimes a stone is just a stone. And sometimes, at a film festival, one movie can stand out by doing more with less.

Jordan Cronk is a film critic and founder of the Acropolis Cinema screening series in Los Angeles. His writing has appeared in Artforum, Cinema Scope, frieze, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Sight and Sound, and more. He is a member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.