Phantom Light: First Cow and Beyond

First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2019)

In a virgin forest, a man hunts for bright yellow mushrooms among the ferns and mossy trees. He pauses when he sees a tiny lizard on its back, delicately flips the creature over, and watches it scurry away. The focus on this minute gesture of kindness introduces and defines both his character and the character of the film, Kelly Reichardt’s rare and lovely First Cow (2019). Within the simplicity of a fable about capitalism, the film (co-written with Jonathan Raymond) harbors layers of meaning, weaving together themes of friendship, home and exile, civilization and wilderness. It does all this while revolving around a docile milk cow, who is at once the fulcrum of this web of meaning and a bovine blissfully ignorant of her significance. Reichardt has said, in an interview with Pedro Emilio Segura Bernal for MUBI, that working with the cow set the tempo for the film, forcing a slower pace, and agrees with Bernal that the film’s point of view draws from the animal’s “innocent gaze.” Innocence is a difficult quality to capture without becoming bland, saccharine, or false, but here it feels both natural and fragile.

The setting is the northwest in the 1820s, before the Oregon Trail brought wagon trains of pioneers like those in Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff (2010). “History isn’t here yet,” one character says of the mostly-unspoiled, primeval woods, but civilization is already invading: the fashion for beaver-lined top hats has sent the first wave of fortune hunters into the region. They range from a humble cook for a band of fur trappers to a wealthy Englishman, the Chief Factor (Toby Jones), who inhabits a stately home attended by liveried Native American servants, and proudly imports the region’s first dairy cow. Her human alter ego is “Cookie” Figowitz (John Magaro), a man with soft brown eyes and a meek, gentle disposition. He is comically out of place among the trappers, a bunch of grunting, brawling caricatures of frontier masculinity. When he sees the cow, tethered in a grove, Cookie smiles for the first time in the movie. A tender rapport grows between them, as he talks flatteringly while milking her. There is just one problem: he’s stealing her milk in the dead of night from the man who owns her.

First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2019)

By this point, Cookie has teamed up with another outsider, the sharp-witted, loquacious Chinese immigrant King Lu (Orion Lee). (They meet cute, so to speak, when Cookie stumbles upon King Lu hiding naked in a bush, and gives shelter to the hunted fugitive.) An instant, odd-couple bond forms between the two men, underscored by Lee’s and Magaro’s beautifully complementary performances and their effortless chemistry. Cookie, an inspired baker, uses the milk to make deep-friend treats called oily cakes, and King Lu gets the idea of peddling them in the nearby settlement. Offering the lonely pioneers “a little taste of home,” they are soon raking in profit, benefiting from the necessary scarcity of their product, which they even sell successfully to the oblivious owner of the cow. This plot is a charming play on the idea that behind every great fortune is a great crime. The pilfering seems harmless, and the fortune is a bunch of shells and beads stashed in a hollow tree, but in this remote frontier, where the only law is that of power, the risks are nonetheless real. The Chief Factor is at once ridiculous, with his pretentious tea parties and confident prognostications on the eternal abundance of the beaver, but he is also sinister, talking in one breath about Paris fashion trends and in the next about the benefits of capital punishment to set an example and enforce discipline.

His grand house is also an ironic contrast with the tiny shack that the two friends share. On his first visit, after standing around awkwardly for a minute, Cookie picks up a broom and sweeps the floor; by the time King Lu comes back from chopping wood, he has brightened the place with a small bouquet of flowers. They fall naturally into housekeeping, foraging and preparing food, sitting on their bunks at night sewing. Both men have been travelers, always moving, removed by countless years and miles from any family or birthplace, which gives added meaning to their domestic idyll even as the restless, ambitious King Lu talks about using their ill-gotten gains to buy a hotel in San Francisco. There is a recurring series of shots framed in the open doorway and window of the shack, looking out at the world from inside a home. When this fragile shell is trashed with casual, punitive violence by the Chief Factor’s goons, the camera stays outside, merely listening to the noise of destruction: the sight would be unbearable.

First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2019)

First Cow is magnificent in its evocation of period and its tactile, almost hyper-real images of the natural world—none of which comes as a surprise after Reichardt and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt’s previous foray into the western past, Meek’s Cutoff. The look and feel of the two films could not be further apart: the earlier movie all parched, wide-open spaces gilded by cruelly beautiful sunlight, the new one all moist, verdant, and claustrophobically dense. The old-fashioned, almost square aspect ratio of First Cow adds to the closed-in feeling and enhances the resemblance to period genre paintings like the luminous river scenes of George Caleb Bingham (suggested by the lovely image of the cow floating downstream on a flatboat). Iconic images like the wandering fiddler in the palisaded fort are anchored by the realism of mud and grimy hands and grubby taverns, and perfectly accompanied by William Tyler’s spare, folky acoustic score. As in Meek’s Cutoff, Native American characters speak their own languages unsubtitled, but in place of the existential conflict in that earlier film, here there is a state of coexistence and cooperation with whites, even if the writing is already on the wall.

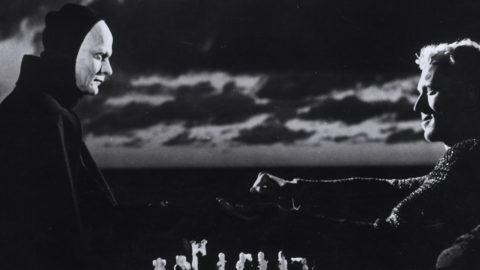

If it is less directly a response to the western genre than Meek’s Cutoff, First Cow likewise critically subverts frontier myths while treating the period with loving care. Interestingly, both of these films are set before the Civil War; most classic westerns are set afterwards, and many are shaded by the lingering wounds of that conflict, which mingles with the elegiac tone of films depicting the last years of the Wild West. Though often characterized as jingoistic celebrations of Manifest Destiny, westerns—at least the best of them—are as much about loss, especially the loss of innocence, as they are about starting over in a new land. Anthony Mann’s Bend of the River (1952), one of the brilliant string of brooding, violent westerns he made with James Stewart, follows a group of pioneers settling in Oregon. It depicts the overnight corruption of a community by gold fever, and the struggles of the scarred hero to shed a dark past, which returns in the form of a morally ambiguous doppelganger. Wherever they settle, pioneers recreate the conditions they left behind.

First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2019)

If the battle between civilization and lawlessness, the struggle to build safe homes and decent towns in a savage wilderness, was ostensibly the great theme of the western, underneath it the real subject is often the fight over resources: gold, cattle, water, and above all land. This conflict pits sheep-men against cattle-men (Shane), powerful ranch-owners against squatters (The Furies), and European settlers against Native Americans. In Anthony Mann’s tragic revisionist western Devil’s Doorway (1950), a desperate band of sheep-farming pioneers are led to a hidden, fertile valley called Sweet Meadows, described as “what all men dream of when they think about home.” But the valley is already home to the Shoshone, who are forbidden by racist laws from staking legal claim to their ancestral territory, and who are finally driven out in a bloody massacre. For one group to find a home, another must be dispossessed. The west’s lands and resources are, paradoxically, both viewed as endlessly abundant and ferociously fought over as though they were scarce. It all comes down to the belief in exclusive ownership over land and animals, and the corrosive drive for profit. First Cow is a radical contrast to western epics full of blazing guns and thundering hoofs, but in its intimate, slyly humorous way, it incisively treats these same themes. The unspoiled lushness of the land and the simple, quotidian pleasures of domestic life and friendship are menaced by the forces of capitalism. It is fitting that the cow’s name is Eve, arriving just at the point where this Eden begins its fall.

Animals are everywhere in westerns—all those overworked horses and cattle being herded to the slaughterhouse—but are very rarely at the center of a story, outside of movies made for children. I did, however, find myself thinking while watching First Cow of Buster Keaton’s 1925 comedy Go West, in part because Eve is a dead ringer for that film’s bovine ingénue (“Brown Eyes”), and because Keaton kids stereotypes of western manhood while developing a sweet relationship between his outcast character and a dairy cow.

When Reichardt programmed a series of films at the Brooklyn Academy of Music that had served as inspirations for First Cow (February 28-March 4, 2020), there were no westerns among them. They included Ermanno Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978), which combines richly textured, unsentimental realism with ravishing pictorial beauty in its portrait of Italian peasant life—and culminates in the brutal punishment inflicted by a landowner on a family that commits the minor infraction of cutting down a single tree. The act of taking something that isn’t yours, or being led astray by greed for profit, lurks in many of these films: the silent, balletically choreographed heist in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Cercle Rouge (1970), carried out by two loyal but ill-fated friends (who meet when one is on the lam); the theft of a bead necklace by the sister who later dies in Pather Panchali (1955), a tender portrait of childhood joys and merciless poverty in a rural village; the selfish ambition of the potter in Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), who abandons his wife in the midst of wartime to take his wares to market. A refreshing outlier among many tragic films, Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I (2000) celebrates people who forage food discarded by a wasteful society, from misshapen potatoes to cast-off produce at farmer’s markets. (All of these films are available to stream online.)

Olanda (Bernd Shoch, 2019)

The extent to which capitalism is intertwined with the natural world is laid bare in Bernd Shoch’s Olanda (2019), currently streaming on MUBI. This documentary very slowly and unblinkingly follows families who gather mushrooms and blueberries in the Carpathian Mountains. We watch them rising before dawn, stumbling around their campsites by flashlight, tromping through the wet, mossy woods, and playing dice at night by lantern light under fields of stars. We see a flock of sheep streaming past a giant cross outside an Orthodox church, and gorgeous panoramas of clouds draped down the sides of pine-covered mountains. Through all of this, we hear people talking, and they are always talking about money: how many mushrooms they have found and how much they will bring, how much gas costs, what they’ve lost gambling on dice, the outrageous sums priests charge to say prayers. We watch middlemen haggling with the pickers over berries and chanterelles, and later observe how the produce travels through the supply chain and how the foragers spend their money. The film’s structure is designed to subtly reveal the way economic networks resemble the branching, spreading webs of mycelium. Mushrooms, which push their way up from the soil, nourished by decay and not requiring light, but often fetching huge sums as delicacies, make a particularly complex and savory metaphor for the ironies of the economy. The miracle of nourishment emerging from the earth, not planted or tended, feeds an elaborate system of transactions, metamorphosing into shoes and gasoline and crosses that dangle from the windshields of beat-up cars.

Despite its starry skies, mountain vistas, and occasional poetic voiceovers, Olanda is mostly about the hard, mundane texture of life spent eternally chasing subsistence: boring drives along rural roads in flimsy cars, drinking cold undissolved instant coffee in the rain, arguing over the lack of cigarettes. These people chat and bicker endlessly about weights and prices because so little can make the difference between getting by and not getting by. The roots of our food supply—of those products we buy because they offer a taste of home or the flavor of an exotic land—run mostly to the same place: the hard work of people we never see.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere. Phantom Light is her regular column for Film Comment.