Parallel Universe: The Age of Dell

See a gallery of adaptations and sequences from the original films.

Whether it’s Shakespeare, the Bible, or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, properties with a built-in audience have been especially attractive to producers almost since audiences first paid to see a film. For nearly as long, comics have provided inspiration (or at least content) for live-action films, at least since 1898, when the Biograph Company produced an adaptation of Rudolph Dirks’s newspaper strip The Katzenjammer Kids. This dynamic has never been as lucrative as it has been for the past 10 years, and it is safe to say that there are thousands of moviegoers who have never picked up a comic book who now have a stake in what happens next to Groot and Rocket Raccoon. There is even going to be an Aquaman movie in 2018 after the notion existed for years as an ongoing punch line on HBO’s Entourage.

The flip side of this relationship is the phenomenon of comics that are based upon movies or that are created from shooting scripts and published to coincide with the release of a film (or, occasionally, years after a film’s release). When a comic is based upon an about-to-be-released film, it is typically just one element of an overall marketing campaign. But not all comic adaptations are published for this purpose.

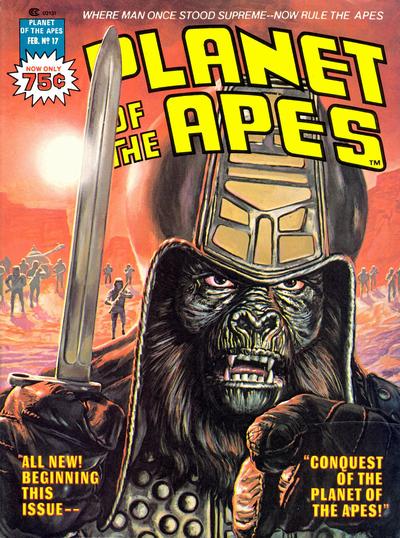

In the mid-1970s, Marvel imprint Curtis Magazines published a series of black-and-white magazines inspired by the Planet of the Apes franchise that began with the first film in 1968.1 Marvel had to send pages to APJAC Productions for approval as the producers wanted to avoid resemblance between some of the human characters in the two formats. This aside, they were relatively faithful adaptations of all five Apes features and gave way to a popular ongoing series of original stories for the remainder of the magazine’s run.

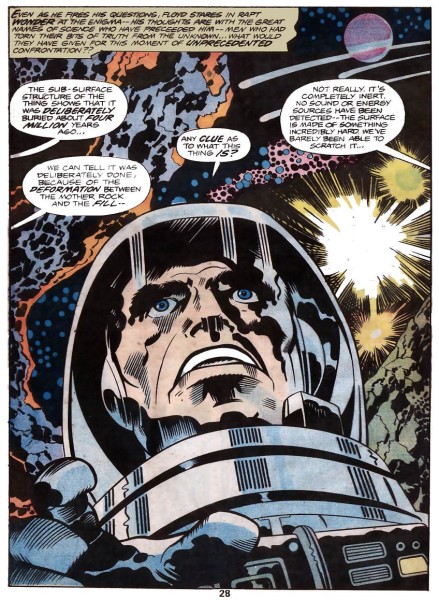

Also, in 1976, the artist responsible for creating much of the Marvel Universe we know today, Jack Kirby, produced one of the most unlikely film-to-comic adaptations ever when he wrote and drew his reimagining of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey for Marvel. Released in a format much larger than a standard comic book, Kirby’s 2001 was a quite faithful adaptation with some departures that were taken from Arthur C. Clarke’s novel which was written concurrently with Kubrick’s film production. Kirby had recently returned to Marvel after spending much of the early ’70s at DC Comics, where his “Fourth World” series of titles including Mister Miracle and New Gods pushed the boundaries of sci-fi comics and general trippy-ness. The worlds Kirby created while at DC were the perfect stylistic laboratory for the outer-space setting of much of 2001, and Kirby took the series beyond the narrative of the film, further exploring ideas and themes introduced by Kubrick.

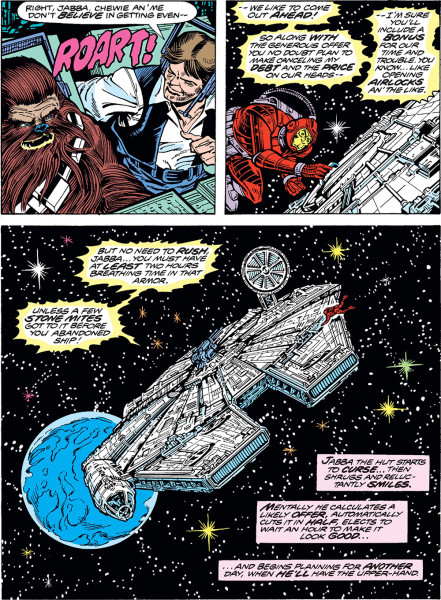

The potential of the symbiotic relationship between comics and film was perhaps first fully appreciated with the release of the Marvel Comics adaptation of George Lucas’s Star Wars in 1977. Not only did Star Wars forever change many of the ways Hollywood produces, markets, and distributes films, but it also introduced a more all-encompassing and lucrative approach to movie tie-ins including comic books. The decision by Marvel to publish a six-issue adaptation of the film is credited with saving the company during a time of financial peril. The first issues hit newsstands before the release of the film, and when it blew up at the box office, it did in comic form as well.

Written by Roy Thomas and drawn by Howard Chaykin, the Star Wars comic was adapted from the screenplay (which was standard practice) instead of the finished film, which led to contradictions including scenes that never appeared in the film and some characters bearing scant resemblance to their movie counterpart (Darth Vader was green on the cover of issue #1). The series of comics was so successful that it led to an ongoing series that featured characters from the film in original stories as well as adaptations of The Empire Strikes Back (80) and Return of the Jedi (83). The Empire Strikes Back is thought to be the first instance of a comic timed with the release of the film in which creators were able to see at least a substantial portion of the film to base their work upon, as opposed to only the shooting script.

Pulling out my copies of all of the Star Wars adaptations recently, I was struck by how heavily read and beat up they were. But in this window of time just before the proliferation of VHS rentals and cable television, there were few ways for a kid to spend time with or revisit these stories and characters other than playing with the Kenner toys that everyone seemed to possess, or reading these comics over and over. Dark Horse Comics published numerous titles under the Star Wars banner from 1991-2014, including adaptations of the “prequel” titles The Phantom Menace (99), Attack of the Clones (02), and Revenge of the Sith (05). Disney bought Marvel Entertainment in 2009 and Lucasfilm in 2012. The license to produce comic adaptations based upon the Star Wars universe returned to Marvel in 2014, and Marvel began publishing new Star Wars stories earlier this year along with new editions of the original Marvel adaptations in anticipation of J.J. Abrams’s The Force Awakens.

There have also been ongoing series of comics based on such popular franchises as Alien and Predator (and like the film crossover, there have been comic crossovers, not to mention such titles as Batman vs. Predator, Superman vs. Predator, Superman and Batman versus Aliens and Predator, etc.) and numerous one-offs based on popular films (including the Frozen adaptation I just encountered at a local comic store). Most casual observers are less aware of that dynamic than of the popular films that have been adapted from comics, but there was an era—and a comic-book company—that produced dozens of movie and television adaptations at a pace and volume that seems unimaginable today.

The relationship between Dell Comics and Western Publishing represented what amounted to the leading comic-book company during the peak years of the industry in the late 1940s and early ’50s. The nature of the relationship was unusual compared to most such companies. A typical comic book company provides the financial resources to produce comics and controls the editorial process (writing, drawing, etc.) while working with an outside company to physically publish their products and distribute them. In the case of Dell/Western, Dell Comics provided the financial investment and decided which properties to publish while Western controlled both the editorial and publishing components and held the licensing agreements with such mass culture staples as Disney and the Edgar Rice Burroughs properties (Tarzan, John Carter), among others.

In essence, Dell Comics paid Western to produce comic books. Keep in mind that during this time between 800 million and a billion comics were sold each year, compared to approximately 60 million today, and Dell/Western controlled close to a third of the market.2 Sales declined with the growing prevalence of television and the chilling effect of the formation of the Comics Code Authority in 1954, which altered content and caused many companies to shutter altogether. But with its wholesome content, Dell/Western did not submit to the Code and instead highlighted a pledge to parents that they would never publish anything that could be considered objectionable. The comics were so popular that for a substantial period of time they didn’t even contain ads, beyond subscription offers for other Dell titles.

The most popular books in the company’s stable were those based on Disney characters, especially the Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck stories created by Carl Barks that remain among the most popular and critically-acclaimed comics ever made. The licenses also gave them access to Warner Brothers and its line of Looney Tunes characters including Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, and friends, and its agreement with the Walter Lantz Studio meant a line of comics featuring the likes of Woody Woodpecker and Andy Panda among others. The widely held impression of the company was that it was a producer of “funny animal” comics, and these types of books did represent the majority of its output.

With all of these licenses, however, also came a large number of adaptations of live-action films and television programs. According to an interview with longtime Dell editor D.J. Arneson in CollectorTimes.Com, the studios would send Dell scripts “by the bundle” and it was up to the editors which ones they would turn into comics. The studios were well aware of Dell’s market share, and adaptations were viewed as an easy way to build advance publicity for an upcoming release.3 Arneson arrived at Dell after it split with Western Publishing, but one can assume a similar approach was in place before this.

Some of the adaptations were consistent with what one might consider traditional comic book content, such as Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (54) or George Pal’s Atlantis, the Lost Continent (61). And given the popularity of Westerns during this time it’s not surprising to see Roy Rogers and Lone Ranger comics and books adapted from television shows such as Bonanza, Have Gun Will Travel, Gunsmoke, and other family-friendly examples of the genre.

More surprising, however, is the number of unlikely adaptations of films one wouldn’t normally associate with comic books. Adaptations of more canonical films like John Ford’s The Searchers (56) or Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo (59) are surprising in retrospect. And it’s hard to imagine little boys and girls giving up their dimes for comics based on King of Kings (61), Quentin Durward (55), or The Story of Ruth (60)—or the life of Adlai Stevenson, but I digress. That didn’t deter Dell from publishing them, which, again speaks to the popularity of Dell and comics in general during the era.

The comics published by Dell/Western were never distinguished by formal exploration or experimentation, and the film and television adaptations also tend to be quite conventional. Dell/Western did publish comics with a higher average page count than its rivals and, because they didn’t have ads, writers and artists could, if desired, create atypically long, uninterrupted stories which allowed for greater character development. Of the film adaptations I’ve read, most had six panels per page (most Dell/Western titles had eight panels per page), almost always of uniform size, with occasional variety introduced by having a panel fill the page horizontally but rarely vertically. More often than not, the covers are the most interesting feature and have made them attractive collector’s items over the years. Some feature photo covers with a recognizable actor or actress from the film while others are painted and reflect the given artist’s interpretation of a moment from the film.

Within these restrictions, it’s interesting to compare the film to the comic and examine what plot elements the comic artists decided to include or not, what plot elements they decided to emphasize, and visually how they decided to approach shots and scenes based upon the shooting script of the film. In some instances, a major scene from the film was also recognized as vital by the comic artists and even treated in a similar manner: for example, the chariot scene in William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (59), in the Dell/Western adaptation drawn by the great Russ Manning (who, like all Dell/Western artists and writers, was not credited). In other instances, a moment from the film is made memorable and even poetic based on decisions made by the filmmaker but left out entirely in the comic, such as the ending of The Searchers or the jailhouse musical numbers by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo, which, understandably, are not in the comic drawn by Alex Toth.

What’s most interesting about these Dell/Western adaptations is the sheer number. Keep in mind that, with few exceptions, these were one-shots. They appeared on the newsstand and then were gone with no continuity of character or story. A small sample of live-action movies adapted by Dell/Western (both together, and, later, separately) includes The Conqueror (56), The Big Country (58), The Left-Handed Gun (58), Dinosaurus! (60), Spartacus (60), Lawrence of Arabia (62), Mutiny on the Bounty (62), The Three Stooges in Orbit (62), PT 109 (63), The Fall of the Roman Empire (64), Zulu (64), Beach Blanket Bingo (65), Lord Jim (65), The Naked Prey (65), Fantastic Voyage (66), and Beneath the Planet of the Apes (70), plus adaptations of all of the Disney features, both animated and live-action.

The marriage lasted from 1938 to 1962, when the two entities split. Dell continued to produce comics under its label until it ceased publication in 1973, with film and television adaptations representing some of the company’s best titles. Western continued to publish comics as well, mostly with the same editorial staff that had been in place, under the Gold Key, and later Whitman, labels until it shut down in 1984.

Comic adaptations of live-action films continue to appear on comic-book shelves. I remember being excited to find Innovative Corporation’s fairly literal adaptation of my favorite film, Psycho (60), on a comic store shelf in 1992. Given Kevin Smith’s love of comics it’s not surprising that the characters from Clerks (94) have appeared in a series of comics loosely inspired by the film. Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (12) was adapted into a six-issue miniseries by the DC Comics imprint Vertigo, and a Django/Zorro crossover was published late in 2014. But unless one was alive during the late 1940s and early ’50s, it’s hard to appreciate just how many comic book companies there were, how many comics were being published in the era and how many of these were published by Dell/Western.

What takes the place of these tie-ins today? Video games and fast-food promotions are both lucrative components of the marketing plans for most tent-pole releases. And as studios continue to bank on big budget super-hero films including the releases of the Marvel films Avengers: Age of Ultron and Ant-Man last year and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and Captain America: Civil War later this year, the marriage between comics and the movies seems tighter than ever. But vertically integrated corporations pursuing “synergy” by cross-pollinating with properties under their domain is rather narrow and even cynical compared to a single company producing adaptations of films across genres, from multiple studios, and of films directed by Ford, Hawks, Kubrick and some of the greatest film artists of the last mid-century.

See a gallery of adaptations and sequences from the original films.

1. There were also Japanese manga adaptations that were published closer to the release of the first Apes film.

2. Figures taken from Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books by Jean-Paul Gabilliet, translated by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen (2010, University Press of Mississippi); and Thomas Andrae’s Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book (2006, University Press of Mississippi).

3. Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books by Michael Barrier (2015, University of California Press)

David Filipi is Director of Film/Video at the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State, where he teaches animation history.