Out of Frame

This article appeared in the September 15, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

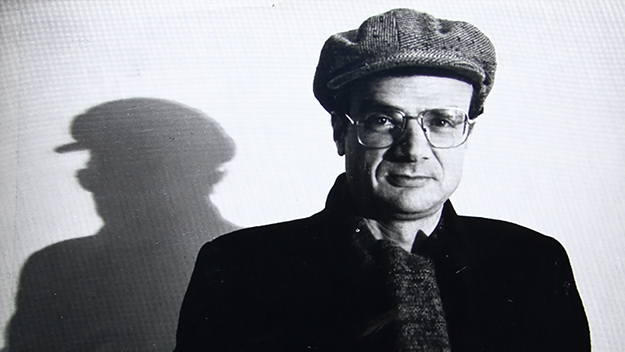

Serge Daney, photo by Joanne Logue, New York, 1982

The Cinema House & the World: The Cahiers du Cinéma Years, 1962-1981. By Serge Daney. Translated by Christine Pichini. Semiotext(e), 2022.

Reading Serge Daney’s The Cinema House & the World: The Cahiers du Cinéma Years (1962-1981), Semiotext(e)’s newly published English translation of the late French film critic’s writings, it’s difficult not to lament the criminally long period of time that the paradigm-thwarting, mind-bending treasures found within have been kept from us. Over the years, Jonathan Rosenbaum has penned more than one jeremiad against the failure of publishers to bring one of the 20th century’s most pivotal writers on cinema to Anglophone readers, arguing that translating Daney “would automatically constitute an intervention of major importance in American film studies,” on par with the importation of Andre Bazin’s work in the 1960s. That particular entreaty occured in a letter Rosenbaum wrote over two decades ago; at that time, editors undoubtedly considered Daney too writerly and unsystematic for academic theory-mills, yet too intellectual for the tastes of that legendary beast, the general reader. Today, both film studies and film criticism have fallen into disarray, the former long ago partitioned and looted by cultural studies and art history, the latter atomized after the shuttering of alternative weeklies and other print publications. Daney’s writing arrives on a scene in which what remains of committed film criticism floats, scattered, like motes in an electronic void, issuing from a shifting roster of online journals, winding wormholes of self-administered substacks, and the miserable marginalia of social-media commentary. In many important ways, this collection arrives too late.

Judging from the writing gathered in Cinema House—which spans, in nearly 600 dense pages, Daney’s first two decades as a journalist, from 1962 to 1981, and is merely the first of four volumes—the writer himself likely would have savored this contradiction. “Cinema is never on time,” he reminds us, in a piece on Thomas Harlan’s Torre bela, a document of the 1974 Portuguese revolution released to theaters only after the farmers’ commune it chronicled had already collapsed. Harlan’s film, he writes, provides “a gaze that is all the more acute—sharp-edged, even—because it fixes the trace of something that has no future.” Daney’s life itself was marked by a similarly disjunctive temporality of near-misses and too-early departures. By the time of his birth, in 1944, his Jewish immigrant father had already been disappeared by Nazi invaders; the critic’s own demise came a mere 48 years later, another life cut short, in the thick of a brilliant career, by the pitiless reaping of AIDS. “Death bestows gravity and importance upon the thing it surrounds (life),” Daney presciently observes in the midst of reviewing Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript, “and the camera’s frame operates much in the same way on the shot it contains.”

Daney started early, as if spurred on by foreknowledge of a truncated life span. He published his first film criticism at age 18, for a two-issue journal he founded with two school friends called Visages du cinéma. Daney’s first piece from Visages, on Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo, helps open the collection and is already rife with brainy brio. He joined the ranks of Cahiers du cinéma in 1964, following the early triumphs of the Nouvelle Vague, and took the helm of the magazine in 1973, just after the apogee of its post-1968 Maoist period. He remained at the journal until 1981, when he left to write regularly for Libération, the Paris daily co-founded by Sartre, where he would publish on not just cinema but television and sports. (Selections from this period are included in The Cinema House as some of its concluding entries.) In 1992, he founded the renowned Trafic, a quarterly dedicated to serious contemplation of cinema, only to pass away shortly after the publication of its second issue.

Unabashedly passionate, vigorously erudite, and mercilessly elliptical, Daney’s writing travels far and wide, covering Hollywood films, the new European cinema of his era, and film festivals around the globe, in articles that range from a few paragraphs to thousands upon thousands of words, testifying to a young writer under the spell of not just cinephilia but cinephagia. Taken together, sinuous rhythms and elevated abstractions unify fragments written years apart, with Daney’s incantatory powers and philosophical insights nearly taking precedence over, yet never entirely losing their grasp on, the films themselves. Daney’s finely wrought prose allows 21st-century readers a refreshed sense of what, to him, constituted auteur theory. The notion of the auteur has by now devolved into, at worst, a hackneyed laurel employed by hero-hungry misogynists, or, more usefully, a familiar scaffolding for film programmers. But reading Daney, one is reminded why one speaks of auteur theory, when one might as well speak instead of, say, peintre theory, or sculpteur theory, or danseur theory: Daney imagines the operations of a film as akin to linguistic ones. His analyses show directors playing with meanings and referents, utterances and enunciations, and he is most centrally fascinated by the ways in which cinema signifies through intervals—in the gaps between shots, between images and sounds, between actors and mise en scène—much as a literary critic might ponder the aporia that churns in the chasms between word and word, and between sign and signified.

During the period covered by The Cinema House, however, Daney did not consider his engagement with cinema as a mere language game. “Cinephilia is not only a particular relationship to cinema,” Daney stresses in a 1977 interview with Bill Krohn that opens the book; “it is a relationship to the world through cinema.” For Daney, the most central question of the ’60s and ’70s was that of militant cinema, an insistently liberatory filmmaking that could counter the ideological stranglehold held by the spectacle of official media. These films strive, he says, “to extract a popular essence of the masses and construct a lovable symbol of that essence.” They ask, most fundamentally, “what can an image do?” They are the films with which he falls most deeply in love, as with Harlan’s, or, above all, Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s Here and Elsewhere (1976). “One tends to find one’s own doxa, imaged, in them, without seeking to explore that very deeply,” Daney says in a reflection on Hải Ninh’s The Little Girl of Hanoi (1974). “One is somewhat obligated to love these films transversally, as if despite themselves, when they are affected by a slight excess.” Such moments of fervent engagement with the politics of his own era are when this collection addresses our present moment most directly. Daney demonstrates that a critic’s role is not only to speak sincerely about cinema as it functions now, and what it means now, for the benefit of contemporary readers, but more importantly to speak to those readers who are yet to be born—like militant cinema itself, an impossible but necessary task. Too late, perhaps, but timely nonetheless.

Ed Halter is a writer and film programmer. He teaches as critic in residence at Bard College and is a founder of the venue Light Industry.