On Sidney Poitier in Edge of the City (1957)

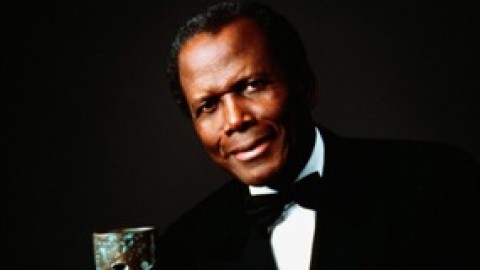

Sidney Poitier is the most valorized black performer in film history, and also the most patronized. Only the second African American to receive an Oscar nomination for a leading role and the first to win, Poitier was the lone black A-list star of the studio era, and arguably held that distinction until the 1980s. At the height of his career, his name was synonymous with integrity, self-respect, and understated resolve. But with the rise of the Black Power Movement, he came to be regarded as a conciliatory, non-threatening figure, too benign for the “By Any Means Necessary” generation and symbolic of a quaint, even embarrassing drive to succeed through civilized, non-revolutionary conduct. This image endured, as evidenced by how the con-man protagonist of John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation (and the character’s real-life inspiration) talked his way into privileged white society by feigning a family connection to Poitier.

Of course these judgments, as is often the case, were founded on scant evidence and oversimplification. There was always pragmatism to Poitier’s good-naturedness—never sacrificing his dignity, Poitier’s approach was typified by eschewing impotent rage and bringing his (and humanity’s) best qualities to the fore. He may have agreed to build a chapel for a cluster of bossy European nuns in Lilies of the Field (63), but when he signs his name in the cornerstone it’s clear that through his skill and resourcefulness, something permanent stands where nothing stood before. He may seek the blessing of his white fiancée’s parents in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (67), but in a scene that still evokes strong emotion, he rebukes his own disapproving father: “You think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.” And in Norman Jewison’s groundbreaking In the Heat of the Night (67), he decisively inserts himself in Rod Steiger’s police investigation, famously declaring to those who mock his first name, Virgil, that back home he’s called “Mister Tibbs.” When a racist suspect slaps him in a greenhouse, he readily returns the blow.

All of these traits appear in abundance in one of his earliest and least-known roles, dock foreman Tommy Tyler in Martin Ritt’s uncompromising feature debut, Edge of the City (57). Blissfully married to Lucy (Ruby Dee) and popular with all the stevedores except the vile, bigoted Charlie (Jack Warden), Tommy takes introverted newcomer Axel (John Cassavetes) under his wing, encouraging the troubled young man to lean on others for support. A man who stands with other men is 10 feet tall, Tommy proudly and repeatedly asserts. Soon Axel is a fixture in the loving, vibrant Tyler household, and confronting his past in a series of confessions beautifully played by the attentive, compassionate Poitier and the raw, soul-searching Cassavetes.

While Axel’s emotional baggage ostensibly stems from guilt over his beloved brother’s death and fear of being exposed as an Army deserter, his repressed homosexuality constitutes the film’s subtext. Cassavetes and Poitier convey this fact discreetly, in Axel’s more-than-shy resistance to his buddy’s matchmaking schemes and his admission that wherever he goes, “there’s always a guy”—Charlie, his Army sergeant, his father—to remind him he’s not man enough. Registering no scorn or even surprise, Tommy is only drawn closer to Axel by this implication. A fellow outcast who’s overcome life’s obstacles through force of personality, he will stand in for his friend’s lost brother, nurturing Axel’s reticent personality and making him feel buoyed and accepted.

This may suggest that Poitier’s Tommy is a “Magical Negro” like Uncle Remus or Bagger Vance, but the film plays very differently. It is Tommy who has the rich inner life, and while he welcomes Axel into the fold, he’s far too busy in his roles as husband, father, and boss to devote himself entirely to his comrade. Rather, he subjects Axel to the possibilities of a loving family unit and a rewarding work situation, empowering him to thrive in the discovery that not all life experiences need be degrading. One is hard-pressed to think of a warmer, more authentic depiction of marriage than that of the Tylers, which owes everything to the chemistry between Poitier and Dee. They seem not sitcom-happy but truly content, even (especially) as he chides her fanatical devotion to social causes and faux-regret for the career she gave up to marry him. They warm in the glow of one another, and it’s easy to see how proximity to them would be restorative to one who’s known only dysfunction.

Equally astonishing is the unobtrusive fact of Tommy’s authority on the harbor. He heads a crew of white dockworkers who respect him and even call him “sir.” Though it’s clear that Charlie means him harm and will use Axel to incite a showdown—foreshadowed by the Chekhov’s-gun appearance of baling hooks early in the film—it is Charlie who is the aberration. Like Poitier himself, Tommy is canny about his public image. He smiles constantly and defuses tension with jokes, but on inspection, his humor is self-aggrandizing: he claims to be a billionaire who owns most of the real estate in lower New York and only works the waterfront for kicks; he disarms a sullen Lucy by citing her good fortune at receiving a dance offer from such a handsome man as he. Tommy can be serious when circumstances demand it, but he believes that most troubles will pass in “a couple, three days.”

Dennis Lim, writing in the Los Angeles Times, identified Edge of the City as the first in “an early Poitier specialty, the black-white buddy movie.” In quick succession the rising star made Something of Value (57) with Rock Hudson and The Defiant Ones (58) with Tony Curtis, earning an Academy Award nomination for the latter. In these and subsequent roles, he retained his nobility, even when nobility was out of fashion, and his comportment in the industry forms a dialogue with his characters’ struggles to manage expectations in a world that burdens them with more freight than they bargained for. In Edge of the City and in life, Sidney Poitier stands 10 feet tall.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.