NYFF: Robert Frank on Film

The Present

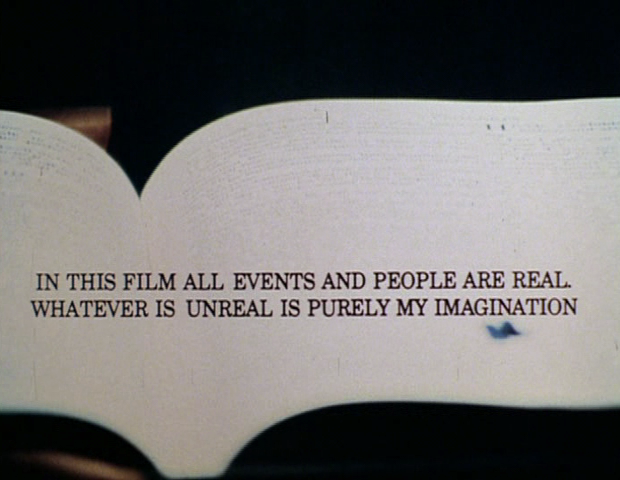

The first time I saw The Present, the rueful, digressive video essay Robert Frank produced when there were—in his words—“another 1,347 days until the year 2000,” it was during an eccentric program at the Museum of Modern Art of films somehow concerned with the notion of “free time.” Frank’s short came after a Humphrey Jennings short from 1939, a Looney Tunes cartoon called “Roller Coaster Rabbit,” and a fragment from Josef von Sternberg’s The Case of Lena Smith (among other selections). I knew Frank primarily for The Americans, the tide-changing collection of photographs he produced after taking his first wife and their two young children on a two-year series of road trips around his adoptive home country. (Frank came to the States from Switzerland in 1947.) Nothing in that revelatory book anticipated the disarmingly candid, direct mode of address Frank takes on in The Present.

On an uninformed first viewing, the film comes off as a charming lark. Frank prowls around his cottage in the tiny town of Mabou, Nova Scotia and his cluttered Bleecker Street loft, leaves jokes and vignettes half-finished, lets his attention wander, and tries to decide what sort of movie he wants to make. Slowly, you start to pick up on the film’s darker, more portentous shades: the two proper names—Pablo and Andrea—that disrupt the film whenever they appear; the black crows that move around on its edges; the game of dice that ends the movie with a discomfiting jolt.

Its glancing epiphanies take just as much time to register as such. “The day is January 26,” Frank mumbles midway through The Present over shots of the fog-shrouded Nova Scotia coastline at dawn. “I was celebrating a new jacket sent to me from Switzerland.” Then comes a cryptic warning from Frank to “wait until later” (what for?) and a breath-catching shot of Frank’s wife, the painter June Leaf, framed against the sky. Another second, and the film abruptly reverts to an image of a smaller scale: a shot of three black crows rooting around in the snow. In the movie’s second-to-last passage, shots of the couple’s well-used hotel room—rumpled white sheets, piles of silverware, June’s wet hair hanging from her unseen face in ropes—mingle with images of the city on a rainy, mist-covered morning over a solo piano composition (the video’s only non-diegetic music). Moments like these alight on Frank’s films with minimal fanfare, linger for a few seconds, then go as brusquely as they came.

Restless, prickly, and reclusive, Frank tends to shrug off critical readings of his work. But I suspect he would have appreciated the idea of The Present concluding a program of films about how people use their free time. In nearly all of Frank’s films—especially the cluster of short video works he’s made since The Present in collaboration with Laura Israel, his editor of 20 years—spare time is a challenge, a burden and a field for play. The role that Frank adopts in videos like Home Improvements (85), The Present, and True Story (04) is that of the solitary man with time to spare and thoughts to be kept at bay. These movies all track the movements of fidgety narrators who need to keep re-affirming their points of contact with the world beyond their heads, renewing earlier pledges to attend to business beyond their memories and dreams. The more time they have to kill, the more room their minds have to drift away from what Frank variably calls the present and the “outside.” It’s this, I think, that accounts for the odd way these videos have of languidly digressing, then suddenly contracting, re-tightening or cutting themselves off. Scenes unfurl luxuriantly and unhurriedly, then end as if with a self-directed reprimand: Enough of this; let’s keep moving.

Me and My Brother

There are countless examples of this sort of thing across Frank’s later video work: the moment in The Present when, passing his camera curiously over a horse, he prepares to give it its name (“this animal is called…”) before cutting away abruptly; the vignette in Home Improvements in which he films a fly crawling on his windowpane then, as if hoping to rush the ending, brushes it away with a finger; the scene later in that film in which, after delivering Jack Kerouac’s line about fame being “like old newspapers blowing down Bleecker Street” over a shot of some of those very papers, he cuts to another image before finishing his own sentence (“—in New York”); a visit to the beach in True Story that’s hustled along by impatient cuts and verbal directives (“Let’s look at this instead!”); the mischievous manner in which Paper Route (02), after following the daily course of a newspaper deliveryman from night into morning and door to door, just ends at an arbitrary stop. In Frank’s videos, there is always an effort to break up blocks of time, to keep the eye so busy that introspection, self-pity, and regret never have time to bring it under their influence. (It’s difficult to know how the responsibility for these films’ inimitable editing rhythms—and the emotional patterns they create—should bed istributed between Frank and Israel. The characters around which the later videos all revolve are clearly versions of Frank, but one wonders to what extent Frank’s onscreen persona emerged only in Israel’s editing room.)

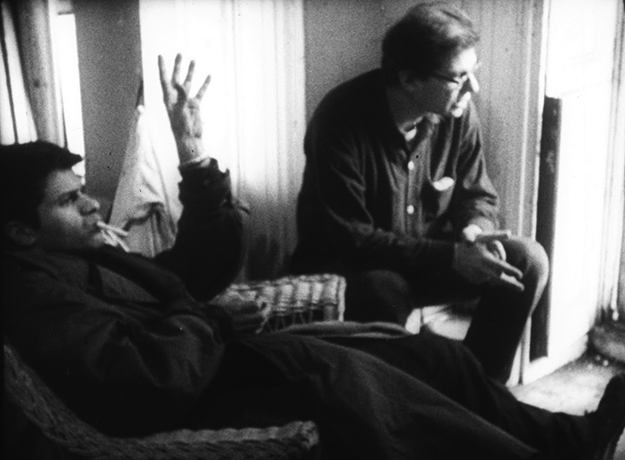

Frank would have reason enough to brood over the past. His life, as his films often insist, has been punctuated by traumas and catastrophes: his separation from his first wife Mary after the publication of The Americans; the death of their daughter Andrea at 20 in a freak plane crash over Guatemala; their son Pablo’s affliction with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and, it eventually emerged, schizophrenia, which he battled for decades. Pablo committed suicide in 1994, a decade after Frank included footage in Home Improvements of the two of them catching up during a hospital visit.

Pablo and Andrea haunt Frank’s work; few of his videos fail to keep their memories close. But to write off all these movies’ odd formal gestures as acts of mourning or ways of staving off grief would be to indulge in precisely the sort of easy psychologizing that Frank’s films consistently disavow. If Frank’s videos are grief exercises, they’re just as much exercises in attention, acted out in the first person by characters to whom attention doesn’t come easy. “I’m always doing the same images,” Frank admits while pointing the camera at his own reflected image late in Home Improvements. “I’m always looking outside trying to look inside, trying to tell something that’s true. But maybe nothing is really true except what’s out there. And what’s out there is always different.”

***

Pull My Daisy

Don’t Blink: Robert Frank, Israel’s new documentary about Frank’s life, is the second high-profile portrait of Frank to emerge this year. In July, The New York Times Magazine published a lengthy profile of Frank by Nicholas Dawidoff that lingers over the making of The Americans, gives an illuminating account of its subject’s upper-class Swiss upbringing, and breezes perfunctorily through most of his films. (The only mention of Paper Route, one of the deftest and most quietly affecting of Frank’s movies, is to misidentify the film’s newspaper deliveryman protagonist Bobby MacMillan as a “letter carrier.”) Given the most time are Frank’s first film Pull My Daisy—the rambunctious Beat classic he made with Kerouac, Alfred Leslie, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso—and Cocksucker Blues, the long-suppressed documentary he made of the Rolling Stones’ chaotic 1971 American tour.

Viewable only at extremely rare screenings or on gloriously low-res video transfers in which Mick Jagger’s stage gyrations show up as dancing blobs of light, Cocksucker Blues is Frank’s most fully developed comment on the dangers of having too much time to spare. The Stones’ lawyers balked at the film’s occasional, brief scenes of backstage debauch, but what’s striking is how often the band abstains from the orgies and raves that develop around them. They spend most of the film loafing around, listening to their own music, heaving TV sets off balconies, and killing time. Voices layer over one another; scenes roll on until tedium starts to set in. When the band take the stage, they tighten up with the knowledge that time is suddenly short—a realization not unlike the one that governs the cuts in Frank’s later videos.

Dawidoff’s Frank is as elusive as his most notorious film: a grief-haunted, restless, sometimes ill-tempered grouch who drifts between homes and prefers the company of drifters or junk art collectors to that of his elite art-world admirers. Israel’s film doesn’t contradict most of those suggestions, but her Frank is warmer, more mischievous, impish and tolerant. Don’t Blink comes off less as a public profile than as a personalized gift from an artist to her collaborator, which makes it from the start a more likeable sort of enterprise than any Times profile. I confess to having been aggravated by the new film’s many buzzing, cut-and-splice montages of contact sheets, film clips, and archival photos, which usually come with puzzling soundtrack choices. You can link Frank fairly directly to Tom Waits, Patti Smith, and even Yo La Tengo, who named one of their best songs in tribute to Pablo and Andrea, but none of these figures’ music feels particularly tuned to the visual and rhythmic patterns of Frank’s photographs or films. How to score a film about Frank is, admittedly, an unsolvable problem. At one point in Israel’s movie, Frank hints at why he likes Super 8 film: “There’s no sound. That made things simpler.”

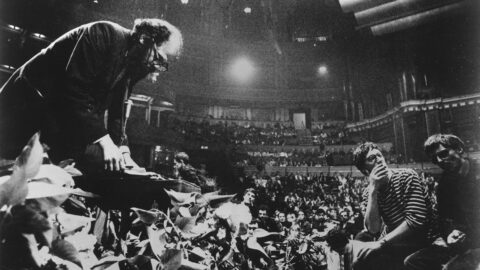

Conversations in Vermont

And yet there are reasons enough to admire Don’t Blink, for which Israel and her collaborators unearthed a trove of rare, wonderful archival footage and set it off against endearing new scenes of Frank ambling about at relative ease. We see Frank defending his films against a hostile crowd at a 1971 NYU press conference, then driving around in 2015 gathering loose, playful footage after his own fashion. (“We’re making a movie!” he tells a street promoter dressed as the Statue of Liberty whom he obviously knows.) More revealing are the clips Israel includes of Frank bristling against his questioner’s demands during a video interview from the mid-Eighties: “I’m gonna be edited in and edited out. It’s not my style, but I’ll do it.”

“It’s not my style, but I’ll do it” could be attributed to most of Frank’s public appearances, including his participation in Don’t Blink. “Well, I guess I have a comfortable life, living in New York and here,” he tells Israel after one question in reference to his life in Mabou. “What do you want? More?” During another filmed conversation, Israel’s team tentatively starts projecting moody, evocative film clips behind Frank’s head, which prompts the following memorable exchange:

Frank: This is exactly what I hate—to have the artist here and the images behind his head.

Israel: What we’re doing now?

Frank: Yeah.

Israel: Well, then, let’s cut!

Israel’s last line in that back-and-forth—together with her decision not to leave these moments on the cutting-room floor—testifies to her ingrained respect for Frank. She’s willing to acknowledge, as few of Frank’s nosy profilers are, that his ways are not always hers. Unsurprisingly, having collaborated with Frank on all his video work since The Present, she gives much more space than Dawidoff to the films Frank made after Cocksucker Blues. Nearly all of Frank’s films are represented, usually at length. Energy and How to Get It (80), Frank and Rudy Wurlitzer’s charmingly sketchy fiction about a genius inventor cut down by the dictates of Big Energy, shows up in the documentary’s first few minutes. Sanyu (00), Frank’s tender video tribute to a Chinese painter with whom he’d been close before the latter’s death in 1966, makes a prominent appearance, as does the retroactively heart-wrenching Conversations in Vermont (69), in which Frank traveled to the experimental rural school where Pablo and Andrea were then enrolled, to talk frankly with both teenagers about his limitations as a parent.

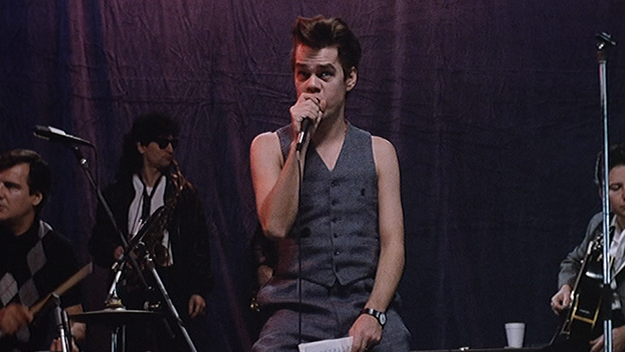

Candy Mountain

Israel glides over the more tumultuous passages of Frank’s personal life, particularly the dissolution of his first marriage, but doesn’t ignore his failures as a filmmaker. Candy Mountain (87), the fiction feature Frank and Wurlitzer made together with an impressive lineup of their artist and musician friends, ended up clumsy and weirdly leaden. Frank’s gift was never for dramatic exposition; in Candy Mountain, he indulged his impulse to suddenly abandon the scene at hand too infrequently for his own liking and too often for the needs of the movie.

Frank made Candy Mountain just two years after Home Improvements, and it would ultimately be in that earlier film’s then-nascent and still under-recognized format—the short video essay—that Frank would find a style which gave him the freedom to digress, flit around and hurry himself along. Frank strikes me as temperamentally far from the Beat poets with whom he often hung out in the Fifties and Sixties, but the virtue he guardedly attributes to them at one point in Don’t Blink was one he clearly tried to live up to himself across his work in photography, film and video: “They didn’t know where they were going, but they went forward in whatever direction they chose to move.”

Thanks to Andrew Lampert, Marian Luntz and the staff of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.