NYFF Interview: Sky Hopinka

Playing with vocabularies of documentary, travelogue, essay and song, Sky Hopinka’s short videos lead us on nomadic journeys through physical, emotional, and mythical dimensions of the American landscape. A tribal member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and descendent of the Pechanga, Hopinka was born in Ferndale, Washington, and has travelled widely, shooting in indigenous lands and along roads that bisect them. He describes his videos as “ethnopoetic,” a term that indicates his nuanced critique of anthropological modes of representation and his creative advocacy of indigenous cultures past and present. Hopinka studied and taught Chinuk Wawa, a language rooted in the Lower Columbia River Basin, and Ho-Chunk, originally based in the Great Lakes, spoken today in Wisconsin and Nebraska. Linguistic pedagogy informs his approach to video, which he sees as a language for experimentation and play.

In Kunįkága Remembers Red Banks, Kunįkága Remembers the Welcome Song (2014), Hopinka’s grandmother recalls a site in Wisconsin where indigenous tribes first met Europeans. Jáaji Approx. (2015) folds fleeting images of skyscapes, forests, deserts and highways into audio recordings of Hopinka’s father, who sings and tells stories of the powwow circuit. Its title combines a Ho-Chunk word for father with a reference to the inherently approximate nature of translation and representation. In I’ll Remember You as You Were, Not as What You’ll Become (2016), texts about the Ho-Chunk Nation written by anthropologist Paul Radin preface vibrant images of powwow dancing, and footage of the late Anishinaabe and Chemehuevi poet Diane Burns. Such dense meshes of visual and verbal referents perform what Hopinka calls a kind of trialogue between different knowledge systems and their approaches to place. Dislocation Blues (2017) also adopts a triple perspective to explore the significance of Standing Rock, the Indian reservation in North Dakota where Dakota Access Pipeline protesters gathered in 2016. Earlier this year, Hopinka published his first book, Around the Edge of Encircling Lake (Green Gallery Press), combining writings, essays and calligrams to discuss video in relation to identity and landscape. Hopinka is currently based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a Radcliffe Filmmaking Fellow at Harvard University, and is working on his first feature film.

Hopinka’s latest short, Fainting Spells, constructs a fictive myth for the Xąwįska, or the Indian Pipe Plant—used by the Ho-Chunk to revive those who have fainted. In anticipation of Fainting Spells, screening on October 6 and 7 in Projections at the New York Film Festival, Film Comment spoke with Hopinka.

Landscape seems a good place to start a conversation about your work. I’m struck by the attention you afford particular places, and the great variation of landscapes we see in your videos. Can you orient us a bit? What brought you to these places and how did they impact you?

I grew up near Ferndale in Washington State, about 10 minutes south of the Canadian border. My mom and stepdad worked at the Lummi Casino and, when it closed, we moved to Southern California where they worked at Spotlight 29 Casino. I was 13, and I found myself in the desert in the Coachella Valley.

The landscape and climate must have been so different there. No pine and cedar trees…

Nothing like where I had been, where I was close to the ocean and I could smell the sea and feel the breeze. And then I was in a valley and it was totally different. The move was really hard, actually. I was in middle school. It was a hard time in general but also really good because I got to spend a lot of time with my maternal grandmother, Sylvia.

Did she teach you her tribe’s language, Pechanga?

No, she didn’t speak it. She was of a generation that didn’t. Her mother had—but had also been taught to feel shame about it. That was my great-grandmother. She went to an Indian school in Riverside, California, and I remember visiting her, and how she’d call me “Sky Rocket.” So, I’d spend a lot of time with my mom and grandma and learned about the powwows and the trail through them. That’s how my parents had met. My mom was a dancer and would learn dance from her mother and pulling moves from Gene Kelly musicals. We’d all practice in the living room, with my older brother and younger sister.

What’s the trail like?

It’s like a circuit. Powwows happen all over the U.S. Primarily we went to ones in the Northwest, until we moved to Southern California, where there’s a whole other circuit that people would come to from quite far away.

It sounds like a formative experience, in Southern California, with your mother and grandmother. But a complex one…

I was depressed. But from that time on, I became comfortable travelling and felt free to move to different places. So, I went to Washington when I was 18. And from Palm Springs to Riverside, California. When I was about 23, I moved to Portland, Oregon. Most of this was on my own. I did a lot of driving back and forth. These long drives, 22 hours straight, four or five times a year. This was pre-GPS, and as a sort of game I did a lot of calculating. If Los Angeles is x miles away and I drive at 75 miles an hour… I’d know when to leave and I’d get to know the route. Parsing out landscapes with time and distance was one of the ways I began to feel more comfortable with the road and traveling.

Driving and the road are really important motifs in your videos.

Roads are lines that bisect indigenous lands, and they’re also spaces in themselves, these little bubbles. When I was a kid, I remember travelling on the trail and enjoying the space inside our van, a little world that you make en route somewhere. Arriving at and leaving from powwows was such a drag because you’d have to set up and tear down camp. But being in the van with all my toys, it was fun. Like being at powwows when camp is all set up and everyone is settled in and you can just be present and explore and run around.

Would you listen to music in the van?

There’d be music or conversation. My mom sometimes listened to cassette tapes that they’d recorded to learn new songs. I liked the background noise of music or conversation and being able to dip in and out of it. I still find that comforting. It felt like a home in a nomadic environment.

I feel like you’re talking about your videos now. The video is a nomadic world itself. It contains different soundtracks—conversations, songs—and sights as we’d see from the window of a moving vehicle. The experience of watching and listening is one of dipping in and out, engaging different levels of attention.

Sometimes I miss that feeling of being a kid in the back of a powwow van, floating along, oblivious, and safe.

I’ve read that you started making videos around the same time that you began learning Chinuk. Could you talk a little about the processes of learning languages—and of learning video as a language? I’m often struck by how different we are when we speak in different languages—there are some things you can or can’t express.

I would not be making videos were it not for my language learning, or I wouldn’t approach it in the same way. The framework that learning and teaching languages gave me also fed into other areas of my life. I’m interested too in the idea of fluency. What does it mean to be fluent in a language? Do you feel like you can take short cuts, play with it, fuck with it? When you reach that level in a language, you arrive somewhere special because you can feel comfortable and break the rules, do what you want. With video work, it’s a bit the same.

Learning and teaching language also taught me to be comfortable in my own skin and be okay with performing or being in certain social situations. Language is a kind of support. When I started out, I took a basic video class offered by Portland Community Media, and the rest was learned from YouTube tutorials and blogs. I tried to imitate techniques and try different modes like documentary. I didn’t go to film school, and that led to my method being more exploratory—what can you say and what can you not say? Going to grad school at UW-Milwaukee helped me nurture that approach further. Saying the wrong thing teaches you about a language’s rules. Same for video. It’s about ideas of fluency, proficiency and experimentation, and searching for when things fall apart.

This becomes very interesting in your videos because they use different modes—or vocabularies, grammars. In Fainting Spells, we see direct observational footage, play with digital errata, scrolling handwritten text, and landscape shots. I’m interested in the way you layer these elements as different systems of knowledge and representation within a landscape.

I feel very conscious of the fact that when I’m taking a shot of a landscape, it’s coming from a feeling of wanting to participate in it somehow—and of not quite being able to get at it. Stopping at the side of the road and shooting some video, there’s always a feeling of not being as connected to the landscape as I could be. Driving 2000 miles across the landscape, am I a part of it? I try to slow down, to walk, to take pictures and shoot video. It can be hard to get to landscapes because they’re cordoned off with fences or trespass signs. You know that feeling of seeing a mountain or a hill in the distance and searching for a vantage point for it, trying to reach it physically? It’s like that.

Do you think you’ll ever reach it? Can you ever reach it?

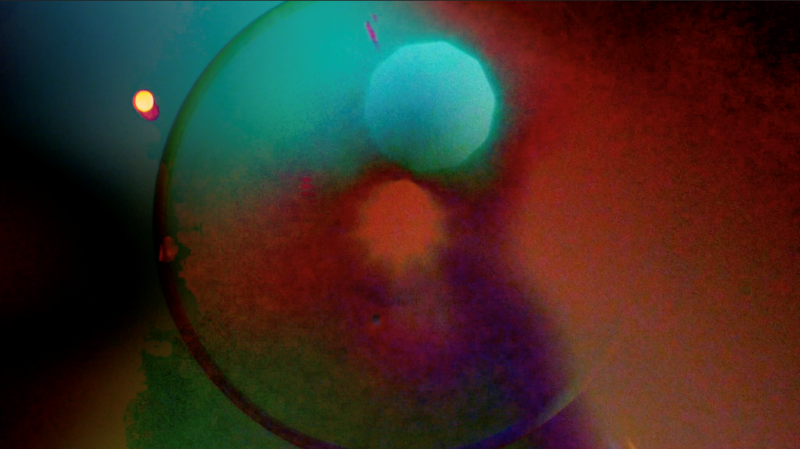

No, but I’ve been thinking a lot about color in relation to this. I shoot something and afterwards I adjust the colors to make them vibrant. The way a camera records an image makes it so washed out as a way to gather more information from the sensor. It reminds me of the flat ethnographic image that stores as much information as it can. I want to adjust the white balance and saturation, to make the image as vivid as I remember the experience.

So, color is a way of tapping into the memory of an experiential present—and presence.

Right.

What’s the camera? Is it a portal to access places, or a barrier from them?

It can be both. Culturally, growing up as a Native American in this country, and as a brown man, you’re very aware of how others perceive you. Am I being seen as being a threat, threatening, or out of place? Having a camera can help in this context because sometimes it makes you seem harmless. But sometimes having a camera makes you look more like a threat, especially if you’re documenting violence from authority figures. So, it’s basically a no-win scenario, and always a crapshoot, and always a series of questions I have to ask myself before I go out: am I walking through a portal or climbing over a barrier?

But I also think about what I’m allowed to film and shouldn’t film for my community—what and whom should I film and when should I switch off the camera? There’s an exploitative side to representations of indigenous cultures, and I’m so wary of that.

The video you made at Standing Rock, Dislocation Blues, seems relevant to this.

I waited to film in places where everyone knew they were being filmed and were ok with that. I wouldn’t shoot where people were camping and eating, their tents, yurts, tipis, and private spaces.

Do you show your videos to the people in them?

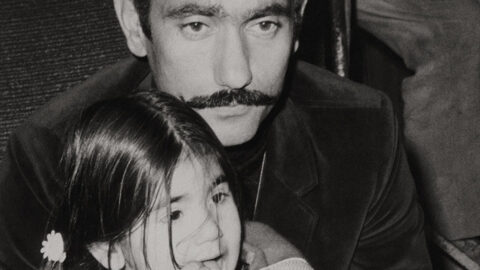

I showed Cleo Keahna cuts of Dislocation Blues as I was going through it—he’s the one who appears via Skype and discusses the camp at Standing Rock. My dad had seen Jáaji Approx. and yeah, I try to be diligent about making sure people are being represented in a way they’re comfortable with.

It’s so personal, about your father and his songs and memories of his tribe. How about landscapes and places that you know less well, what’s it like shooting there?

That’s a good question. Usually I ask, am I allowed to film this, am I allowed to be here? Or, should I be here? I try to follow my gut with that, if it feels wrong then it probably is wrong. But I’m not perfect and neither is that approach. Still, I try to inform my present practice with previous successful choices and mistakes.

And they’re quite different modal verbs, aren’t they? Can and should. One is often more about private property law, and the other about the ethics of representation. I’m saying this having grown up wandering all over the place in Wales, where there’s a Right to Roam law. I’m struck by the large amount of private property in the States.

Walking is something I do a lot, to get to know a space. In Visions of an Island [2016], I was on an island that’s 14 miles across and seven miles wide. I set off on a walk across the middle of it, and it was far, but I wanted to do it. It felt right, walking and shooting video, trying to find out what’s significant and how I can relate to this place as an outsider. What is significant to me as a visitor and what is significant to the locals? I do that in cities too. I walked a lot in Auckland one summer, and another summer in China, and try to pay attention to what I’m not looking at.

With all your travel, and all the shooting, is there somewhere you’ve felt most intensely connected to place?

There’s this hill a bit south of where I’m from in Washington, which appears in Jáaji Approx. and Fainting Spells and another video recorded at different times of the year. Something about that landscape does all the things that make me feel at home.

“At home” is an interesting phrase for someone who has moved home a lot.

Moving around a lot, and not knowing where that home is, yeah, there’s something special in that place though—the trees, the light at different times of year, and the heat or cold. I’m interested in the gesture of taking a photographic record when you’re travelling alone. The moments feel constructed but in different ways. When I shoot, I wonder if I’m looking for the landscape, the people, or the light.

Sometimes those elements fold into one. I’m thinking of the sand dune in Fainting Spells. Where is that?

Southern Colorado. It was such a striking landscape. I got interested in finding moments to shoot when the light was above and harsh. The final scene of Fainting Spells is shot there too, the one with families and children and the river. I liked the shot and I wasn’t sure what to do with it.

Yes, I remember. You’ve digitally manipulated it so that it separates into different colors and, as you pan across the landscape, layers of the image seem to peel up off the ground.

I was looking for a closing shot for the film and experimented with that one. What is it saying aside from what it’s presenting as?

Is that reflective of your process, to improvise? Do you write shot lists?

No, usually I find opportunities to shoot and just go with what feels natural. If I had one, the only thing on my shot list would be “bring your camera.” As going out with a camera is a challenge for me. And I’m constantly keeping track of how I’m shooting, to notice if I am drawn to the same things—and if so, why? I try to be deliberate with that. Even although I’m shooting on video, I want to be economical because it takes a lot of time to go through the footage whenever I shoot every little thing, and I want to make it count.

Your videos are personal, sometimes they feel wandering and improvised, but they’re not confessional. Instead, they foreground your advocacy of communities and are as political as they are personal. Are they for you? Are they for the people and communities you film?

When I was making music, I was making songs for myself because I didn’t think anyone would want to listen to them. With videos too, they’re initially for me—as I’m the one sitting alone in an editing room for hours with them. They screen places, but I’m the first audience that watches them and they should feel true to me. Simultaneously, I think of me as myself and then me as a member of these indigenous communities and try to hold these videos to a standard that is grounded in respect for the people and traditions I’m filming and representing.

Your first book was published this year, Around the Edge of Encircling Lake. How does writing inform your video work?

I’ve always written, on and off, and it was always, like music, something I shied away from sharing. It’s turned into a process that helps me work through these videos adjacently and collaboratively.

At Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival this month, you showed five films interspersed with readings from your book. One of the readings was an essay (“American Traditional War Songs”) which discussed Jáaji Approx. on quite a formal level and in a formal tone, and whose expansive footnotes led us into a more personal and lyrical register. I interpreted this as an analogue to your videos in which scrolling handwritten text is often in the direct first-person and is a counterpoint to more distant or formal landscape shots.

I’d just finished Fainting Spells when I wrote that essay’s footnotes, this summer. I was interested in bringing different voices into the book. I suppose it’s a form of mapping, exploring different avenues via different voices. It’s similar when I walk—I want to see where roads lead to and where they end.

You mentioned music too.

I started out playing guitar and bass, I’d record, I was in a band. With my sound design today, I may loop 10 seconds of something to make it longer or think about the difference between silence and room tone. I’m thinking, what is the most I can get out of this one clip or riff? Sound and image both work like this for me—I’m asking, what can I do with this material? What are its possibilities?

This reminds me of what you were saying about language fluency. When you get fluent enough, you can play with it. Tell me about installation and screenings as different modes you’ve played with recently.

At Berwick, Fainting Spells was installed in a tower of the town’s walls on a single screen. In the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee and the Bockley Gallery in Minneapolis, it’s the three-screen installation version. In Projections this week at New York Film Festival, it will be the single-channel version in a cinema. I’ve enjoyed making these two different iterations of Fainting Spells and seeing how they occupy these different spaces. For the three-channel version, it’s broken up into three parts, and when I was making it I also put in these other recordings of my dad I had which aren’t in the single-channel version. It was a week after his death, and I just wanted to hear his voice.

Who is the cloaked figure we see in it?

That was from test footage using green screen cloth I was messing around with, and in the editing process I felt that it reminded me a lot of the Indian Pipe Plant itself, a sort of human version of it. I wanted the plant represented in some way and this felt like a risky but natural way to do it.

And some of your father’s speech and song used in the three-channel version of Fainting Spells comes from recordings you made that are in Jáaji Approx.? One of my favorite parts is when your father says that some words just can’t be translated.

They can’t be translated or can’t be translated by just one equivalent word. There are times when approximate translation is sufficient.

Right. An approximation. Jáaji is a word for father, so the title Jáaji Approx. is all about the approximate nature of translation and of knowing something or someone. What about the translation of myth?

Fainting Spells explores what it is to learn from a myth. I’m interested in what and how myth teaches us, how it is a presence in present-day native communities, and how it influences how we navigate the world. In Fainting Spells, subtitles begin with a direct address asking someone to tell them the story of Xąwįska, or the Indian Pipe Plant—used by Ho-Chunk to revive people who’ve fainted. That’s a kind of intro. Then we go into the remembrance of the personified Pipe Plant and the imagined myth of how we came to use the plant.

So, you’re seeing myth as a way of understanding or translating concepts too large to grapple with?

Yeah, it’s maybe a way of filtering. It’s easier to tell a story than to say what you mean sometimes, you know?

And so it makes sense that you write some of the myth yourself in Fainting Spells. You’re based at Harvard University this year as a Radcliffe Fellow, and making your first feature film—will that explore myth too?

It will explore writing as a way of respecting myth. There are some myths that cannot be told outside of a tribe, or clan, or a particular time—there are some that can only be told in the winter, for example, and others only in the summer. So, by writing myths myself, I’m participating yet still being respectful. I want these stories to be pliable, and to be part of a conversation. I’m a participant, I’m an active agent in this community, and the feature will be a continuation of this idea. Now, I’m thinking of how to scale my practice of short videos to something as large as a feature. I have a lot of footage, and I’m transcoding it now. It’s shot on the Columbia River in Oregon. I’ll go back there this fall to shoot more, and hopefully be finished by next summer.

Becca Voelcker is a PhD student in Film and Visual Studies at Harvard University, and a freelance film critic and programmer.