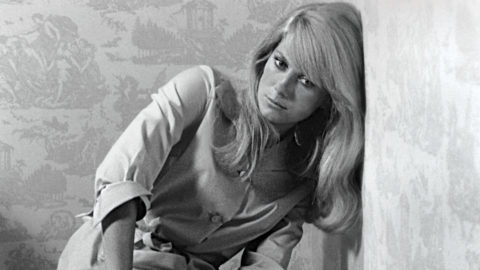

Noblesse Oblige: Helen Mirren

The following is an excerpt from “Noblesse Oblige,” a feature from the March/April 2018 issue considering the career of Chaplin Gala honoree Helen Mirren.

“I’m not the bloody Queen,” Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennison scolds her abashed male driver for addressing her as “Ma’am” instead of her preferred “Guv.” Tennison may not play royalty in the hit British television crime series Prime Suspect, though she does rule there as a queen bee. But over a long career on stage and screens large and small, Helen Mirren, who plays the spiky policewoman, has enacted a raft of bloody Queens, one of whom won her a richly deserved Oscar and swelled her already solid cachet with royalty-loving American audiences.

From her early days in Britain’s National Youth Theater, where her Cleopatra attracted agents’ attention, Mirren has propped up a cottage industry of royals wielding power, libido, and bags of lavishly costumed panache. She played the fourth and, mercifully, final wife of Malcolm McDowell in the ill-starred Caligula (1979). Bewigged and brocaded, she appeared opposite Nigel Hawthorne as Queen Charlotte, the devoted 18th-century consort who tried to keep her demented husband on the throne in The Madness of King George (1994). She drew rave notices for her Elizabeth I in the television miniseries of the same name, and as Elizabeth II in Peter Morgan’s 2013 stage play The Audience, which imagines the weekly conversations between Her Royal Majesty and a fleet of Prime Ministers, all of whom she outlasted. And lest you think she’s done playing monarchs, Mirren is prepping to star as Catherine the Great in an upcoming HBO/Sky miniseries. That’s a pretty pedigreed franchise for an actress who has played more than her share of gangster’s molls, and even there she oozed her own brand of tarnished nobility.

Regal roles may have made Mirren the darling of American Anglophiles, but her long-term appeal extends far broader and deeper. Drop Mirren’s name into a conversation with those old enough to have followed her career from soup to nuts and—man or woman—their eyes light up with a mix of adoration, respect, and ongoing lust. Having joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, where she rapidly rose to play leading classical roles, the actress’s blend of luscious golden beauty, frank sexuality, and sharp intelligence built her a reputation as what the Brits call the thinking man’s crumpet.

It’s easy to see why Mirren keeps getting cast as royals. She has an irreducibly regal bearing and can do haughty on demand. Yet from the start she willingly shed the showier roles for meatier ones. Along the road to making her name in film, Mirren has been revelatory in a host of smaller treasures. She won Best Actress at Cannes as the Catholic widow of a murdered Protestant tangled up with an IRA member in the realist Irish drama Cal (1984). She is terrific as the colorlessly dour housekeeper in Robert Altman’s Gosford Park (2001) who defrosts and dissolves when her Mrs. Danvers–like cover is blown. And she is enormously moving in Fred Schepisi’s lovely 2001 Last Orders as a woolly-hatted blue-collar widow struggling to free herself from a lifelong rut as everyone’s caretaker.

It’s hard to imagine an American megastar like, say, Meryl Streep playing understated supporting roles like these. But like all top British actors, Mirren was trained to move comfortably between ensemble roles in theater, television, and film, and she’s never been obsessed with stardom or with branding herself in a particular genre or character.

To continue reading Ella Taylor’s article, please purchase the March/April issue.