No Home Movie + Grief

Chantal Akerman is one of those filmmakers cursed with having legions of imitators and very few peers. I say “cursed” because the aesthetic tools she developed—extreme long takes, a particular style of frontal or “planimetric” compositions (which she argued obeyed the Second Commandment’s prohibition of idolatry)—can seem dulled by overuse in less skilled hands. (I recall my college film production TA warning me about associating a female subject with her home in a short documentary I was making because it was so “overdone”—and she was right to say so.) Still, there’s nothing like watching one of Akerman’s films; even works like Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 1960s in Brussels (94) or Golden Eighties (86), which adapt more conventional formal strategies befitting their genre, also bear her unique authorial touch and contain a degree of the personal. It’s talking about her films that often becomes difficult, for she had the great gift of turning the banal, the overplayed, and the obvious into something wholly unique, usually by asking us to do something as simple as gaze and experience time.

Akerman’s final film, No Home Movie, which in part documents her elderly mother Natalia’s decline in health, is oftentimes painfully intimate. Rather than show the unsavory aspects of the end of life—hospitals, hospices, or the myriad accessories that assist failing bodies—the director focuses on conversations with her mother, and allows her physical decline to speak for itself. Yet because of Akerman’s family’s history—her parents fled Poland to Belgium while teenagers, and her mother was deported to Auschwitz while her father spent the war in hiding—there’s no such thing as a lighthearted trip down memory lane. Sitting together in a teal kitchen, daughter prods her mother to remember the man besotted with her aunt who got her papers to enter Belgium; a brief round of “you were the most beautiful mother” and “you were an adorable child” compliments; then a disagreement about whether or not the King of Belgium was a Nazi.

No single work by Akerman attempted to address Natalia’s experiences in a comprehensive manner, but the Holocaust and its legacy—both as the daughter of a survivor and racism in contemporary Europe—preoccupied her and manifest themselves throughout her work. Aside from her visit to Israel, prompted by what she felt was an increase in anti-Semitism and documented in 2006’s Là-bas (which also contained discussions of family history), there’s 1980 Dis-moi (80), an hour-long documentary for a French TV series about grandmothers in which the director interviews old female survivors of the Shoah in their homes. Like Akerman’s mother, these women speak directly about the horrors they’ve experienced, and then, after a time, get bored and return to domestic chores or watching TV while the cameras are rolling. The Holocaust also figures in her most famous work: in an interview shortly before her suicide, Akerman explained that “[my mother] went out of the camps she made her house into a jail. That’s Jeanne Dielman. Now I can tell that, but I was not aware of that when I did it, you know?”

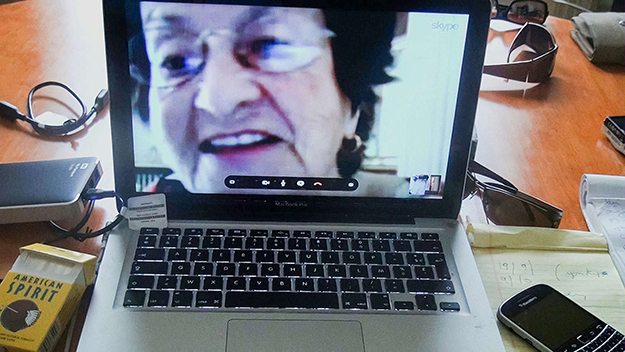

The candid mother-daughter chats in No Home Movie, which frequently run without cuts, are uneasy not simply because they touch on topics that Akerman has waited a lifetime to talk about, but because her mother says she feels uncomfortable being filmed. “I don’t want everyone to hear what I have to say to you,” she tells her daughter over Skype, without irritation. “ I want to show how small the world is,” Akerman responds, smiling. But this joviality (faked or real, we can never know) isn’t lasting. In one of the film’s most heartbreaking moments, her mother’s caretaker—a Spanish-speaking woman who, either because of a language barrier or ignorance, doesn’t seem to understand the Holocaust—whispers to Natalia after lunch, “She knows you are anxious, but she doesn’t know it’s because of her.” “It would make her sick,” Natalia replies. Unlike the earlier conversations in the kitchen or over Skype, the camera is set up in another room, diagonally angled toward her mother’s formal dining room. Her mother and her caretaker are distant figures at the table, their heads cut off whenever they move in closer, sloughing away any sense of familiarity and intimacy with each frame. We’re eavesdropping on family tension, made even more unpleasant by virtue of the fact that the person who’s being talked about has not only heard it too, but still chose to show it to the world and violate her mother’s wishes for privacy. The ethical implications of this decision call into question her entire project, as well as past films like News From Home (77), which incorporates letters from mother to daughter that were never intended to be presented publicly. Yet Akerman’s insistence on filming can equally be understood as a daughter who has taken a radically different approach to life than her mother, and we witness—in the film as a text and in how she navigates her mother’s objections in the moment—how such openness about personal matters is a fundamental component of her identity and independence. In the portrait Akerman creates of her mother, we come to understand that her stubborn commitment to filming is more than simply being stubborn.

Nevertheless, such dynamics between family members remain fraught, and they aren’t easy to witness (especially as outsiders). Akerman also courts a sense of anxiety with extremely long shots of the Israeli desert, the majority of which are taken from the window of a moving car. These views of the big, wide world—one that the mildly agoraphobic Natalia refuses to see—break up the everyday goings-on in the house and green parks of Brussels. (Akerman’s mother is repeatedly shown turning down offers to go on walks, and lives in one of those immaculate homes that speaks to a deep-seated desire to remain indoors; the director also includes brief shots of peering out of a window onto the streets, like a small child that wishes to go outside but is forbidden to by their parent.) Taken together, these views of sun-parched vistas, smattered with scrub and battered by violent winds, come to form an apt metaphor for experiencing grief and mourning a loved one. Like that initial wave of grief, their implicit hopelessness is made even more agonizing by their length.

And yet, as any person who has grieved knows, you keep moving forward through space and time; the world continues despite your loss. In these bleak landscapes, expansiveness doesn’t necessarily come to elicit hope until you let it (assuming you’re buying into the seven stages of the Kübler-Ross model). Still, this isn’t a self-help manual or therapy via art: No Home Movie immerses you in a feeling and holds you there. What you ascertain from the experience, or how it connects to your own losses, is just as personal as the film is to Akerman.