Make It Real: On Cinematic Autobiography, Part 2

One Cut, One Life

In a written diary, there’s really only one point of view. Depending on how it’s written, depending on how generously the author imagines and conjures the experiences and feelings of others, you can get a version of other perspectives, but it’s one literally and wholly created of words written by the authorial hand. But in autobiographical cinema, even if a filmmaker forcefully expresses his or her point of view, using the camera as an extension of his or her gaze, and editorializing and shaping experience through the edit, the machine employed offers at least a chance of a hint at another’s perspective. All it takes is a look on someone’s face, and no matter how totalizing the filmmaker’s POV, we can imagine that other subjectivity. It’s a tension inherent to the process, simultaneously making a mess of the notion of autobiographical cinema while giving it the potential to enthrall, agitate, surprise, and transcend. While a written diary radiates out of a single POV, a filmed one ricochets, often wildly, among the camera, the filmmaker, and his subjects (one of whom is the filmmaker himself).

In Ed Pincus and Lucia Small’s One Cut, One Life, which screened at the 2014 New York Film Festival, the filmmakers and Pincus’s wife Jane discuss another distinction between two methods.

ED: Just as a thought exercise, suppose I was an author.

JANE: Suppose you were an orphan?

ED: An author. A writer.

JANE: It’s not the same thing. It doesn’t impinge on everyday life. On the naturalness of moving around.

ED: But you might have an interaction that you read about a half-year later.

JANE: So you read about it. But it hasn’t affected everyday life.

LUCIA: It’s not impacting it as it’s happening.

JANE: Which you fucking filmmakers love to do.

Of course Jane is entirely right about film meddling with the everyday to a degree that written autobiography does or need not. But it also shows Jane, while not our main subject or narrator, asserting a point of view in the scene that the film accommodates. That the two filmmakers each have different feelings on the subject at hand offers an even more fractured perspective. It also creates space for the audience to move around within. Their real lives may be compromised, but the film only gains from the complexity. It’s when subjects push against the first-person apparatus—consciously or otherwise—that worlds of thinking, feeling, and being open up to us.

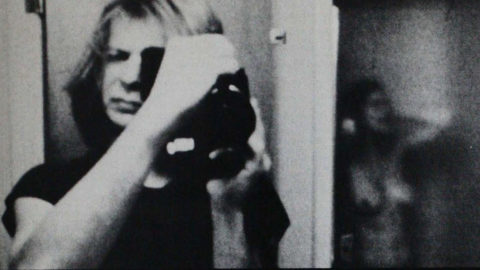

Diaries (1971-76)

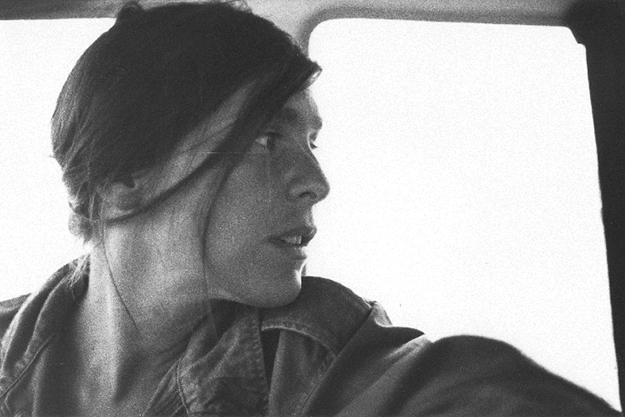

As evidenced by Pincus’s astonishing Diaries (1971-76) (80), which screened as part of BAMcinématek’s Diaries, Notes and Sketches: Cinematic Autobiography series, this discussion had been 40 years in the making. “I feel like I’m sacrificing myself for your film,” Jane says to Ed in 1972, just as he’s embarking on a first-person account of their lives that would extend deep into the decade. “I don’t consider it my film.” But whether or not either of them ever considered it her film, Jane does wind up being the heroine of Diaries (which, when trying to persuade his wife to go along with the later project, Ed actually affirms in One Cut, One Life). This seems to have been at least partly by design, since the arc constructed for Jane’s emotional and sexual development proves to be the film’s most satisfying.

In a sense, Jane is the ideal subject for someone else’s autobiographical film. On one hand, she expresses herself articulately and forcefully, offering up fears and objections that we might be feeling on her behalf. On the other hand, she gives an awful lot to the process, and accepts, albeit grudgingly, the camera’s presence during extremely intimate moments. In the opening stages of the Diaries, Ed and Jane’s marriage seems at risk because of Ed’s unapologetic pursuit of extramarital relationships. Jane tries out other relationships as well, but their instability seems to exact a greater toll on her. So as months and then years expire in the narrative, one expects to discover that they’ve separated or divorced, or to simply never see Jane again. But instead she keeps turning up. They’re still married. And she’s still pursuing her own desires and pleasures. Their marriage isn’t a cautionary tale and neither is Jane. She’s figuring this out for herself as well. It frankly lets us see our storyteller in a better light. Ed eventually seems less like a selfish or foolhardy man, taking advantage of sexual liberation at the expense of those who love him, than as a sincere explorer of the self, and of partnership and attachment. Other women in his life are given chances to reveal themselves, to suggest fuller lives than Ed’s self-portrait will allow, but it’s Jane that makes the strongest impression—it’s Jane that defies whatever shape the film is giving her. And it’s Jane that simultaneously invalidates and validates the project.

There’s a scene in which Ed talks to his colleague and mentor, Ricky Leacock, at what seems like a weekend party. Children and spouses are all around, but the two men huddle next to the window to talk shop while someone else holds the camera (a student, a lover, both?):

ED: You made the intellectual decision not to be private like other people.

RICKY: I was enormously private.

ED: There’s a big cost to privacy that I wasn’t interested in. But then on the other hand there seems to be a cost to being public. Lots of time I feel that you strain to be public and you don’t really want to.

RICKY: Because it could be embarrassing—to be public. Suppose what emerges from you is not acceptable to the public.

ED: Funny enough it sort of drives me in that direction. You do want to make these. At the same time you don’t want to make them, you do want to make them.

It’s an interesting discussion, and both men have poured themselves into these matters. But they’re also both clearly proud of the discussion, and excited that it’s self-reflexively happening on camera. Then right as Leacock is illustrating his point by surmising how humiliating it would be if the camera revealed that he was queer, they’re interrupted by loved ones. Real life invades their “real talk.” A not candid conversation about living candidly only becomes candid when it’s counteracted—underscored by Leacock glancing back toward the camera sheepishly, his sheepishness being the scene’s one true thing. We’re not necessarily Jane in that moment, but because of how she’s functioned in relation to Ed and the film, we’re able to assume a critical distance from the men. We’re able to recognize that everyone else in this room has to pay some kind of price in order for these men to live publically. Maybe we even recall what she said: “I feel like I’m sacrificing myself for your film.”

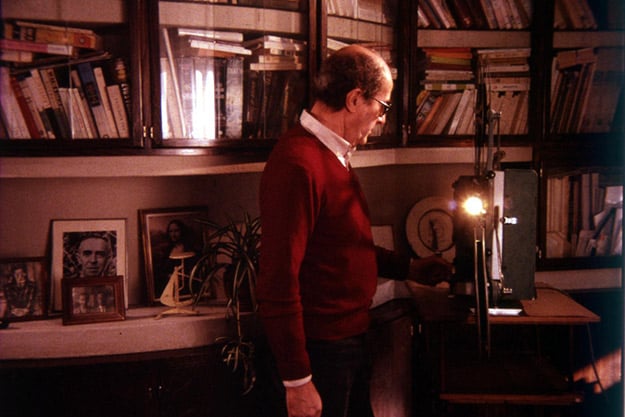

The Visit, or Memories and Confessions

Though it works in a completely different mode, Manoel de Oliveira’s The Visit, or Memories and Confessions, which screened just once at this year’s New York Film Festival—albeit in handsome, Academy-ratio 35mm—gains a crucial, critical dimension through the brief appearance of the filmmaker’s wife, Maria. The majority of the film takes place in the filmmaker’s longtime home, which, through intermittent, but consistently awkward direct address, he tells us he’ll be shortly vacating. These monologues take place in his upstairs office, allowing him to tell his life’s story, as well as that of his family’s, with the aid of photographs and home movies. At times these orations veer into confessions, especially when de Oliveira cops to being preoccupied with purity and virginity, and enraptured by his young actresses, though his stilted delivery suggests a complicating self-consciousness. Alternating with these monologues are sequences in which the camera tours the house and its environs, but instead of assuming the director’s POV, we’re guided by a poetic dialogue between an unseen couple that has alighted on the property for the first time.

Somewhere amid all of this, the camera retires to a field on the property, to find Maria. She speaks briefly and unsentimentally. She says that the initial years of their marriage were wonderful and exciting, with both of them employed in making Manoel’s movies. But that after they started to have children, she became responsible for them while her husband continued with his films. That living with the great artist Manoel de Oliveira has been difficult, unfair, a trial. It’s possible that her husband was behind the camera as she said this. It’s definite that she was offering it to his film—his only-to-be-watched-after-my-death autobiographical film, no less. And it makes the movie. It allows us, encourages us, to question the matter and mode of the director’s self-presentation. As with Jane in Diaries, it both punctures and aerates the balloon.

These are still men’s stories, with differing degrees of acknowledgment of and infiltration by a woman’s POV. Unsurprisingly, things play differently in One Cut, One Life, which Pincus directed alongside Lucia Small, with whom he collaborated on a previous feature, The Axe in the Attic. A uniquely dual exploration of the self, the film’s burden falls heavier into Small’s hands, physically and otherwise, as she wrestles with the sudden death of two friends, along with Pincus’s declining health in the face of a terminal prognosis. This time around, friction from Jane is also felt by Lucia, and all three parties seem equally uncertain about how to process the scenario. So when Jane expresses again her reservations and resentments over the film we’re watching, it doesn’t necessarily come across as a corrective. Instead it registers as one POV among several—with the camera being passed among them, and redrawing the geometry from one shot to the next.

Diaries (1971-76)

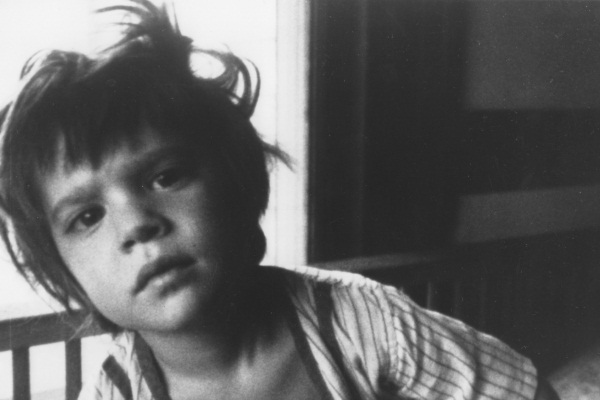

Its the fulfillment of an ethic and idea present throughout Diaries, nodded toward in The Visit, and shared by filmmakers like Ross McElwee and Doug Block (whose wife, Marjorie, plays a formidable, re-diagrammatic role in his films 51 Birch Street and The Kids Grow Up). During the last scene of Diaries, Jane is cutting Ed’s hair outside of their Vermont home, which the camera records, unattended, from the porch. Their children Ruth and Ben are scampering around, until young, habitually aggrieved Ben begins to wail. Ed reacts to it sarcastically, then tries to make it better, and draws the admiration of Ruth, who calls her parents by their first names.

“That’s neat, Ed,” she says. “What do you mean?” he asks. “It’s funny,” she says. “Neat is not the same as funny in my book. But then again my book probably isn’t your book,” the film diarist says. “Because if my book was your book then you would be me, and I would be you.” “Right,” she says, affirming but with a waver of uncertainty. She understands more than she realizes, while the rest of us probably understand less than we think we do. Floating around out there, somewhere in the distance between her and him, him and the camera, the camera and the audience, exhibitionism and exploration, is a reason to keep rolling.