Make It Real: Medium Well

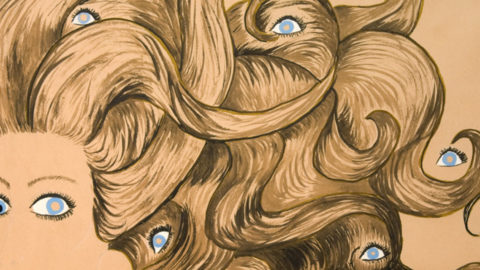

Field Niggas

So let’s get this straight. What makes a feature feature-length, and what makes a short, short? Is one over and the other under an hour? By that logic, is a three-minute movie categorically equivalent to a 60-minute movie? And by categorically equivalent, you mean equally unsuitable for distribution, yes?

It’s been thus for a long time, ever since a certain sweet spot between quantifiable value, cyclic efficiency, and metronomic three-act structure yielded the 90-minute standard, the cinematic equivalent of the foul shot. If everything comes together as it should, it just feels right. Yet it’s weird that three-pointers and half-court heaves have more of a place in the market than dunks, bank shots, and turnaround Js. That latter arsenal is destined for YouTube or Vimeo, bizarrely ignored by watch-what-and-how-you-want subscription-based outlets like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu, all of whom do fine by 23-minute sitcoms—the layup of lengths. So where does that leave the mid-range jumper?

Convento

It’s actually alive and well—perhaps more alive than it’s ever been—even if few people know what to call it or where to put it. Which often means ignoring, disqualifying, or miscategorizing it. Theatrical practice and journalistic policy favors films with a running time north of an hour. In two recent examples, The New York Times refrained from reviewing theatrically-released films like the 46-min Stations of the Elevated (81)—first out of NYFF in 1981 and then again in 2014—and Jarred Alterman’s 50-min Convento (10). Yet the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences actually considers anything over 40 minutes to be a feature, and anything below to be a short. (The only other measurement I can think of that pivots so dramatically from short to long, small fry to big guy, with nothing in between, is penis size. You’re free to make of this what you will.) I don’t know of any documentaries of less than 60 minutes in length to be recognized by the Academy in recent years. Even festivals can struggle with how to program mid-range films, as they run afoul of the feature-length vs. short films dichotomy—they’re either too short to justify a feature slot, or too long to work within a program of truly short films. (“If you have a mid-length and a feature-length version of your film,” it says on the submissions FAQ page for the Tribeca Film Festival, “we prefer that you send us the feature-length version.” Oh do you now.)

There’s another solution, of course: honor the midrange. Which is what RIDM, the Montreal Documentary Festival, has been doing for years. RIDM is not alone in this—IDFA, Visions du Réel, and some other festivals also have slates and prizes for mid-length films—but the festival also smartly showcases these films as the headliner of their respective programs, with (one or two) shorter works building to a mid-length main course. This year’s eight-film International Medium-Length Competition included Khalik Allah’s Field Niggas (59 minutes), the late-breaking sensation that went from YouTube anonymity to New York Times Critics’ Pick in one long, strange, winding year, and Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, and Guy Maddin’s Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton (31 minutes), a film that’s just as hilarious, subversive, and accessibly avant-garde as my colleague Nicolas Rapold says it is in the current issue of this magazine. That the film debuted at this year’s Toronto Film Festival in a shoehorned corner of the lobby of the TIFF Bell Lightbox, even though Maddin is one of Canada’s favorite sons, says plenty more than I can about the disfavored status of the mid-length. Yet here it was in Montreal, on a screen big enough to effectively lampoon the big-budgeted pretensions of Maddin’s semi-serious nemesis and honest-to-god employer, Paul Gross’s Afghanistan-set war picture Hyena Road.

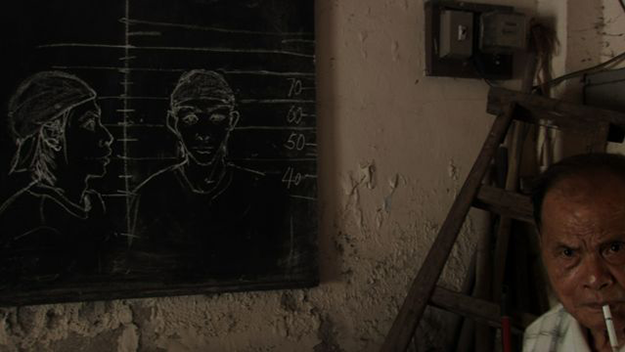

IEC Long

But few things compare to the sensation of walking into a movie theater with no expectations or advance word—enhanced by the sweet disorientation of flying a mere 45 minutes (a mid-length flight, if you will) to alight in a foreign country and tongue—and getting cold-cocked by something singular and new. I felt that in watching IEC Long (31 minutes), the latest by the co-directors of The Last Time I Saw Macao, João Rui Guerra da Mata and João Pedro Rodrigues. It starts with the ludicrous spectacle of fireworks being set off along the water—by hand, via launchers, on massive steel trees, all acts that seems more ritualistic than celebratory, and all recorded (it’s so fucking loud) in observational deadpan. Then, like a pocket Apichatpong, the film seems to flip into another realm. We’re wandering abandoned buildings, we’re meeting an old man who’s some kind of tour or security guard or ghost of the building’s past, we’re confronted by a double exposure of a young boy staring dead into the camera, and we’re dialing back to newsreel footage of what this place used to be: a fireworks factory, the prize of Macao, before it closed in 1970 amid stories of maimed, murdered, and underage workers. In half an hour it manages to be sensational, hilarious, haunting, earnest, and surreal. Any longer and it might have been too blunt, too academic, too legible. Instead there’s only time for fire, smoke, and mystery.

It’s hard to imagine a better setting for a film like IEC Long than RIDM, a festival that’s very discerningly programmed but also unapologetically ecumenical in its appreciation of the nonfiction arts, mixing abstract experiments with festival-tested standouts, five-minute pecks on the cheek and five-and-a-half-hour epics like Homeland (Iraq Year Zero). But the truth is that fine mid-length films have also emerged or gotten crucial pushes from less likely sources, such as Sundance (Abandoned Goods) and Maryland (Buffalo Juggalos), though these still lack the showcasing that RIDM’s juried competition offers, not to mention a sense of the form’s history. In a festival sidebar program called “A Photographer’s Eye: Photography and the Poetic Documentary,” the various lengths of films by Jem Cohen, William Wegman, Agnès Varda, Harun Farocki, Miroslav Janek, JH Engström, Chris Marker—the last four of which were solidly mid-length—spoke to various notions of what constitutes a length appropriate to a chosen subject or concept. An Image (83) by Farocki is elegant, articulate, and perfect as it is, witnessing a Playboy magazine photo shoot from set construction through awkward nude blocking to the perfectionism of banal image making. It’s a complete circuit in 25 minutes, thoroughly capturing an activity and culture without belaboring or reducing for the sake of an external expectation of time. In searching for a time-based analogue for photographs and photography, many of these films seemed to naturally arrive at unconventional lengths. Which calls back to the photographs-in-motion quality of Field Niggas, which manipulates our perception of time more than it adheres to any received conception of it.

An Image

In fact, it’s tempting to conclude that mid-length films are the truest-length films. Considering all of the disadvantages spelled out above—the theatrical, critical, and festival-related perils of being the middle child—only a film that simply must be 47 minutes long would ever choose to be 47 minutes long. There’s great reassurance in that notion, as well as in the likelihood that these films won’t wear out their welcome. Just time enough for fire, smoke, and mystery—or some combination therein.