Make It Real: Listen to Me Marlon

Media literacy is high enough these days that most viewers understand or at least intuit that movies are made from creative and logistical choices. Yet there persists a reluctance to embrace this fact as it pertains to documentary filmmaking. The reluctance is simultaneously dissonant and understandable. Dissonant in that we readily accept the idea of man-behind-the-curtain craftsmanship from narratives that require a suspension of disbelief, while the notion is harder to accommodate with films ostensibly anchored in the real. But understandable in that such anchoring in the real implies, or gets interpreted—seemingly, and crucially, on an instinctive, unconscious level—as transparency, purity, simply what is.

To some degree it’s always been thus, even as definitions and ideas of what is or isn’t documentary have evolved and altered over the decades. Perhaps the accepted lie of reality television has reduced tensions around the matter for some relativity-oriented viewers; perhaps that same lie has enhanced anxieties for viewers who need to feel that some films are, by definition, clearer, less crafted, and more trustworthy, and that those films are called documentaries. In general, though, I think the persistence of worries, misinterpretations and willful ignorance around the matter among audiences, coupled with persistent infighting, disingenuousness, obfuscations, self-righteousness, and insecurity among filmmakers, means we’re not dealing with a trendy debate or status quo that needs to be toppled—we’re facing continuously shifting, unstable ground, as thrilling and alarming as a permanent quake.

So to return to the uncomfortable obvious—documentaries are constructs, made through choices and by creative people. Documentaries aren’t just captured (if at all)—they’re made. In what will be a regular column for FILM COMMENT, I’ll look at how these films are constructed, who makes them, and why you might want to join them on the seductively shaky ground of nonfiction film. For this first installment, I’ll take a look at Listen to Me Marlon, a film that doesn’t just rise above the recent batch of archival-heavy biographical documentaries (What Happened, Miss Simone?, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, Amy, etc.), it also operates as something of a master class on the shaping of character on screen.

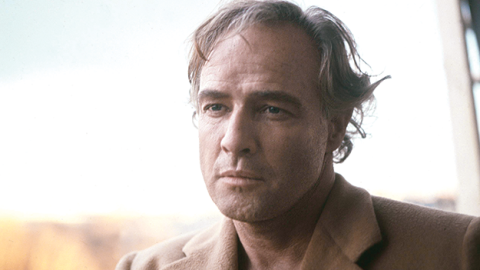

In Listen to Me Marlon, Stevan Riley’s story of Brando as told by Brando, the man that some consider the greatest actor America ever produced delivers what may be his finest performance. Now, that may be hyperbole, but in no way is it impossible. The words, via a mass of previously unavailable audio recordings, are Brando’s; the story, of the boy from Omaha who became the face of an acting revolution, won two Oscars, bought an island in Tahiti, and dealt with devastating family tragedy, is his; the face, as most anyone who lived in the 20th century could tell you, is his; and the character is one he spent a lifetime shaping and presenting. The movie isn’t his, and being 11 years deceased he presumably doesn’t even know about his involvement in it. But a movie rarely belongs to an actor, living or dead.

Last year I spoke to Kevin Kline about the control filmmakers have over the shape of a performance (FC Sept/Oct 2014). “When you give a director a variety of choices, there’s a great deal of trust involved. An abandonment of all control,” he said. “Philosophically you have to just go, ‘He’s going to use what he’s going to use.’ People say, how was it? And I say I have no idea—it all depends on how he cuts it.” Not every actor furnishes as wide a range of alternate line readings as Kline, which can limit the performer’s risk somewhat, but ultimately a performance takes shape, follows a rhythm and tone, and is built in the editing room.

This certainly holds for Listen to Me Marlon, in which director/editor Riley virtually resurrects Brando through an incantatory arrangement of familiar film clips, unfamiliar voice recordings (including a series of home meditation tapes), home video and 8mm footage, a subtle but crucial bit of set-making, and an eerie digitization of the actor’s head and voice—made possible by Brando’s prescient, late-life decision to have it mapped for future employment. An opening salvo from the digitized Brando bust, shown on a TV screen, piercing the silence of his abandoned house (the aforementioned set, moodily approximating the real thing), establishes a conceit in which the actor is not only telling his own story from some ghostly, extra-material realm, he’s telling it to himself. “You are the memories,” he whispers. It’s the ultimate monologue, which Riley underscores by concluding this prelude with digital Brando delivering the most celebrated soliloquy from Macbeth (which he/it slays).

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

There’s good reason after 100 minutes of Listen to Me Marlon to dispute the notion that our narrator is anything like an idiot, that his tale is without significance, and most evidently, thanks to this exhumation, that he is “heard no more.” But the attitude is right. The sorrow, the self-incrimination, the wearied humility, it’s all exactly right.

From this moment on, Riley’s Brando, or maybe it’s Riley’s Brando’s Brando, is simultaneously speaker and listener, performer and audience, activated and remembered, soother and soothed. There’s a roughly chronological arc to the narrative, starting with Brando’s Midwestern upbringing at the hands of an abusive father and alcoholic mother, his effective adoption in New York by Actors Studio maestro Stella Adler, the rapid ascension, the fame and seed-sowing, the decline and comeback, the exile to Tahiti, the estrangement from acting, the cruelly tabloid-ready, Shakespearian family tragedies. But it’s a chronology that’s constantly subverted and redirected by Brando’s emotional and intellectual understandings of cause and effect, the sources of his desires and loneliness and insecurity. There’s nothing pithy about this—Brando was keenly attuned to his own psychology, and Riley’s doubling back to his impressionistic childhood memories, nasty confrontations with his father, and the indelible teachings of Adler, feel fully considered and soundly charted to the man’s development.

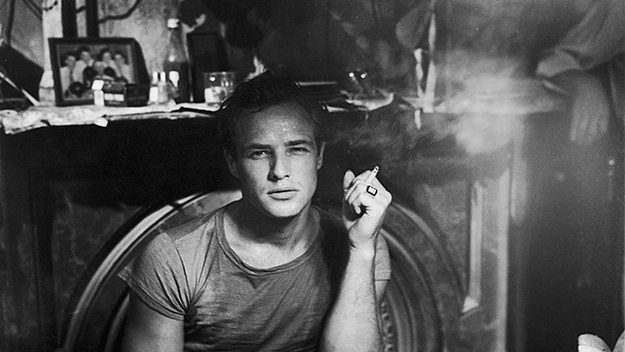

Clips from A Streetcar Named Desire have become so common as to be warmed over, even disempowered, but Riley matches them with Brando’s insights about Method Acting and recollections about his family to demonstrate how the sensitive young man could so convincingly play a character so vastly different from himself. “If I had a scene to play, and I have to be angry, it must be within your trigger mechanisms that are spring-loaded, that are filled with contempt about something,” he says, while Marlon as Kowalski licks his fingers at the dinner table, glaring at Stella. “I remember my father hitting my mother. I’m 14,” and just at that moment Kowalski smashes his hand against the table, the layers and legacies of rage crashed together, as the Method’s notion of “sense memory” is distilled into a single cinematic instant. Marlon isn’t Stanley, but through Riley’s innumerable, music-softened splices of disparate audiotape he’s mining the pain that brought the brute to life.

“There’s nothing about me that’s like Stanley Kowalski. I hate that kind of guy,” he continues, as we cut from Stanley manhandling Blanche to a still shot of Brando’s dad. “I absolutely hate that person and I couldn’t identify with him.” Then the elder Brando dissolves back to Marlon as Kowalski, at first glowering and heaving, then suddenly troubled and confused. “They sent me to a psychiatrist. They thought I was going nuts, losing my mind,” he says. Is Stanley’s visible consternation illustrating Marlon’s talk of his own confusion, or are we learning how Marlon channeled the latter to embody the former? In effect it’s both, meaning Riley is communicating two separate meanings using a single sound-and-picture pairing, which in turn all combines to communicate a larger message about the personal dangers of working and living as the young Marlon Brando. “Putting on a mask. Building a life. And slowly I got into this part,” he says later, and again the sentiment applies both to a role in the actor’s filmography and to the actor’s performance as himself.

Brando’s tone throughout the film resembles that of his 1994 memoir, Songs My Mother Taught Me, in which he plays a voluble, sincere, eccentric, and often achingly self-reflective raconteur. We get candid talk about women and meddlesome filmmakers, the glories of Tahiti, the importance of acting, the absurdity of acting. But the movie transcends previous attempts at getting inside the man thanks to the cache of self-made meditational tapes, which Riley scatters throughout the narrative to restore us back into Marlon’s headspace, back into the private whisperings of a man trying to find some center, some sense of calm. He guides himself—and now Riley, and us—back to a caretaker who showed him affection and safety as a child, back to the swaying branches of trees in the backyard, back to his chosen, and ultimately doomed, paradise in Tahiti. It’s the loveliest, most intimate, most heartbreakingly maternal voiceover since Dianne Wiest guided us to death in Synecdoche, New York. The voice is soft, measured, patient, loving, an externalization of words intended to create internal serenity. And because he’s talking to himself, it’s hard not to hear it as a plea, as inherently loaded, as futile.

Or at least that’s what the handling of the material evokes for me. Listen to Me Marlon is a portrait in the guise of self-portraiture. You could call that deceitful, but I’m not sure who’s being deceived. We know that Brando hasn’t actually been resurrected as a digitized head. We know, from the varying quality and vocal timbre of the audio clips, that his narration has been spliced together and doctored and repurposed. If you’re at least somewhat familiar with Brando’s life and work, you can probably enumerate crucial events and aspects that are missing—events and aspects that you’ve long been free to discover elsewhere. In my estimation, Riley’s achievement isn’t the novel packaging of archival material associated with a famous person, it’s using that form to communicate something delicately profound about human consciousness and mortality. You could easily tell the story of Brando in terms of fame, burning brightly before fading away into fat jokes and ridicule; you could also tell it as a sine wave, rising and falling and rising and falling again. But Riley cuts against all of that to bring us into the head of a thoughtful, troubled, sincere man—a man that, for all of his privilege and money and fame, we can recognize as one of us. He’s the tragic hero onto which we can project ourselves, our own troubled relationships with our parents, our own mortifications over somehow growing up to be like them, in spite of everything.

Whether or not it presents the most factually appropriate or rounded version of Marlon Brando, Riley’s version makes for a thoroughly complex and sympathetic cinematic character. “Through introspection and examination of my mind, I feel as though I’m coming closer to the common denominator of what it means to be human,” Brando says near the end, and it somehow comes across as the legendary star’s greatest achievement. Just to get closer. In Listen to Me Marlon, the man is an actor, and the actor is a pathway toward understanding the man. “All of you are actors, and good actors. Because you’re all liars,” he says. But to Brando, and to this film that ingeniously manufactures him, that’s no condemnation. That’s honesty. It’s also art. The lies are truths.