Locarno Interview: Andrzej Żuławski

The experience of watching Andrzej Żuławski’s breakneck, hectoring, emphatic Cosmos may be compared to being yanked around hither and thither by the lapels until dizzy, or to trying to hop a runaway train—for a second you think you have a handle on it, after that you’re just hanging on for dear life and trying not to be sucked under the wheels.

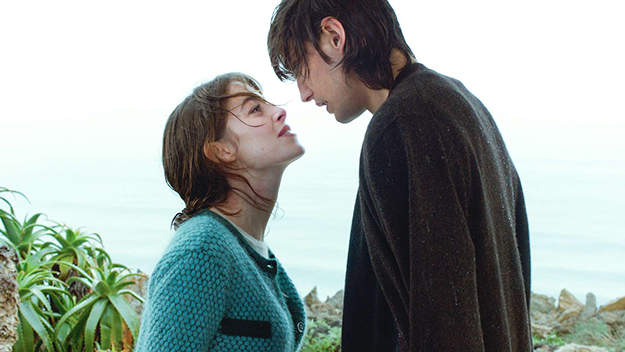

Cosmos, currently in competition for the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival, is Żuławski’s first film in 15 years. It’s an adaptation of the 1965 novel of the same name by Witold Gombrowicz (1904-69), in which two young students (played in the film by Jonathan Genet and Johan Libéreau) living at a secluded country house find themselves assailed by what they believe to be sinister auguries.

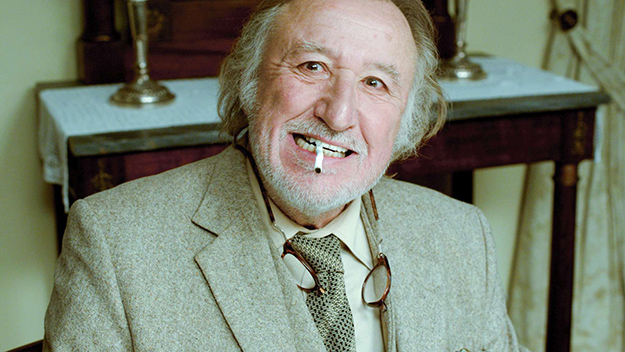

Born in Eastern Poland (part of present-day Ukraine), after attending film school in France and serving as an assistant to Andrzej Wajda, Żuławski began his own directorial career with The Third Part of the Night (71). Meddling from Communist authorities convinced Żuławski that he wouldn’t be able to live and work in his native country as a liberated artist, so he relocated to Paris shortly thereafter. His first film made in France, The Most Important Thing: Love (75), cemented his international reputation, and he would gain a measure of infamy for films displaying a feverish, St. Vitus Dance–like energy, brazen eroticism, and elements of horror and fantasy, as in Possession (81), or his too-little-seen Polish homecoming, the extraordinary Szamanka (96). In recent years, he has become a prolific novelist, though a recent touring retrospective brought his filmography before a new audience, making this an auspicious moment for his reappearance.

At the Locarno Film Festival, FILM COMMENT met with Żuławski on the covered patio of his hotel in Acona, where, at the moment we sat down, a downpour began outside.

I saw you in Montreal around this time two years ago, at the Fantasia Fest. At the time you had some very harsh words for the contemporary cinema, and seemed to be in a fighting spirit.

I still am, because the only thing that I cannot sustain in cinema is boredom, this terrible boredom which assails European cinemas now, and these terrible festivals. Go to Cannes, you’ll die. You went there?

I did not.

Good for you. I have a son who’s 20, and he was at the Cannes film festival this year, because his mother [Sophie Marceau] was on the jury. He phoned me in a panic, because he’s young and he still has so many illusions and so many hopes—I’m happy for that. He said: “Father, I’m dying of boredom! Is it always like that?” I said: “No, not always, but mainly nowadays.” It’s either sheer boredom; or you have to see the film taking things for a serious matter, and you have to take cinema for a serious matter, which maybe it’s not. Or you have the light stupidities, and the only progress in film nowadays is in technology. Technology leads the industry, or the industries. You have three solutions, and in between, once every five or six years, you can see a film which is a film, which is something to see, to hear, to get moved by in a way or another. I’m still very much against [contemporary cinema]. What can we do?

What struck me when watching Cosmos in this festival’s context is that it’s very much a maximalist movie in a place where minimalism is, I would say, the rule.

Look, I’m not yet dead. I’m alive. Speaking profoundly, I love cinema, so I love to see it when I can, and I still love to do it when I can. But the energies are exactly the same as always. An English journalist told me that my film is an extremely radical film. I was listening with suspicion. I wondered, what does he mean by “radical”? It’s chop, chop, chop, straightforward, punching the lines, etc. Maybe it is radical, I don’t know. I enjoyed doing it, and I especially enjoyed working with the actors. I think they are all quite, quite fabulous. I also enjoyed fighting with the book by Gombrowicz. He was such a brilliant and highly intelligent and perverse guy. I was making a film that didn’t attempt to be in a fight with the book—not destroying the book or pretending to destroy the book—but rather be faithful to the spirit of the book while not just flatly filming the book. Making a real film out of it was my goal.

Gombrowicz is very invested in that adolescent spirit, in taking the piss out of things.

It was his attitude. When he was young, when he was old, he had the same attitude. He adored what he called “the green”: that which is not ripe yet. The unripe, the unfinished, the not yet said. He adored that. It was almost a cult or a religion with him. The longer he lived, the more the aesthetic became an ethic. He was living with a ton of young guys. He found this unfinished quality of the human body, of young things, so much more aesthetically appealing than rotten old things. We never tried to discuss that in the movie. That’s him and it’s all right, but it’s not me. You have writers and filmmakers who are constructors, and then you have those who are destructors. Depending on the time, I think, one is more interesting than the other. For all of Gombrowicz’s life, he was a destructor. He was always somehow on the margin of the main road. That made him young up until his old age. It’s extremely interesting, and I would say vicious.

Is that destructive, wrecking-ball quality part of what made adapting Gombrowicz seem important or necessary at this juncture?

I don’t know. Please, what’s important or necessary in cinema? Nothing. “Important,” “necessary”—I can’t understand these words. I do it because the book is lovely and brilliant. I’ve liked the book for ages. I was very surprised to be offered the opportunity to film it. I would never think of it. And that’s it. Now, is it important? No, I don’t think so. What’s important? Locarno’s important? That car over there? No. Or Hollywood? No.

But it seems with the frustration that you were just now expressing with contemporary cinema…

No, I’m not expressing frustration. Please don’t misunderstand me. I was very happy not doing films for 15 years. Maybe it was the happiest period of my life. I was busy with really interesting things, like living. And so there is absolutely no frustration. On the contrary, I bless these times, and now I look forward with a bit of apprehension because the men with the money are thinking that they should make films now, again. And I won’t. No.

Well, you can always disappear into the woodwork again.

No, but I’m 75, so that would be final, and this is the only thing that makes me wince.

Why do you think the opportunity came about now? Do you think your traveling retrospective had something to do with it?

I don’t know. No, really, I don’t absolutely know. I was really amazed after all these years of not being there and not doing this thing, when I went on stage and 2,000 people were applauding me, like these years of solitude didn’t exist. I was really moved. Really. Stupidly moved.

Could you talk a little bit about how the cast of Cosmos came together?

Like all casts in the world—except Hollywood, where very often people are pre-cast. The young guy who is the lead, Jonathan Genet, I found in a theater in France. Not in Paris, but in the provinces. He does a lot of theater, but he’s practically unknown. I discovered him in the provinces, where I went because there are a lot of fantastically gifted and strange and unknown actors there, because the known ones are in Paris and they do resemble each other, maybe not physically but in the way they perform. He’s a wild guy. He’s fantastically interesting for me in a part that we cannot define really. It’s ambiguous. I think that’s very difficult too for him, to endorse this un-clarity, which is Gombrowicz.

The part is really the epitome of the Romantic figure of the pale, longhaired poet pushed to the point of absurdity, yet not quite parodic. These exaggerated Romantic tropes seem to give the film its defining tone: a Romanticism that is pushed beyond Romanticism until it verges on the absurd.

It’s called Surrealism. It’s an interesting interpretation, Romanticism pushed to the point of absurdity, which is called Surrealism.

And he does an extraordinary Daffy Duck impression.

[Laughs] But he can do whatever. The girl, Victória Guerra, was discovered by the producer. She’s Portuguese, and I saw her in two not very convincing films, huge historical frescos, Lines of Wellington and Mysteries of Lisbon. In the first one, she acted with John Malkovich. John told me: “Don’t hesitate. Take her. Take her. She is a talent.” And one listens to John Malkovich, who’s the ham of hams, but very intelligent, totally bright, and so I listened. I did a test. The first shot of the movie was a shot in the mountains when she breaks down, to see if she can do it, and she could. So, she was in the film.

This is the rubber-faced close-up, when it looks like she’s pulling faces in the mirror?

Yeah. The two French actors from the old school, I knew them for years and years, and I admire them, especially Jean-François Balmer, the guy who does the older man. I think it’s an incredibly brilliant performance with the language, with the French. He’s amazing and I always saw him in the theater, and I always wanted one day to have the pleasure of working with him. He’s a great actor. [Sabine] Azéma, who was the wife of Alain Resnais for 30 years, who I respected a lot, though strangely I never thought she was any good in his films.

I would agree with you wholeheartedly. I’ve never liked her more than in this.

Though in some light things where you have to be very quick and witty, she’s very good. And she’s very popular. For a producer, it’s important. And she’s a sweet person. We also had two Portuguese actors, which was easier, as we were shooting in Portugal. It was a small cast, a cast of nine.

How did you go about adapting from a text which is so interior to give it an exterior life, making it something other than an internal monologue? How do you open that up into a film?

You saw the film, so you have the answer. I don’t know if it’s a good film or not, but one way was to try not to fight with the book—though it was still a fight with Gombrowicz’s intelligence, and his traps, which are numerous. It was important not to give it the original setting, which is Poland in 1939, with a bourgeois family pension, and this suffocating, claustrophobic thing, but to open it. This means that it becomes modern, today, somewhere in Europe, doesn’t matter, and this opens all the interior structures of the film. If you do this, if you transpose it, it’s almost like filming Stendhal or Balzac in modern dress. Almost. So the adaptation was something very, very difficult for me. I think I wrote the script three times in order to be absolutely faithful to this mad spirit of Gombrowicz. On the other hand, I didn’t want to just film the book, but to make an independent and free film. That was the fight during this production: accelerating things all the time.

Is Gombrowicz someone you grew up reading? Someone you’ve been with to one degree or another for your entire life?

Yes. For my generation, which was born during the war and raised during Communist times, Gombrowicz was censored, totally unknown in Poland. No books in print, no nothing. He was living, as you know, in exile in Argentina, in Buenos Aires. But we were feeding on his plays and books because he was like air, like light, in those terribly sad, grey, and lying times. Whatever he did looked like a savage provocation in front of the Communist concrete and total boredom and total incapacity to do anything right. My entire generation was a Gombrowicz generation.

I know Skolimowski’s film Ferdydurke from some years back. I don’t know how many other attempts have been made…

I never saw it. “I had everything wrong,” Skolimowski said. Maybe one day I will see it. And there was another one, which is Pornografia, made by a Polish director who changed the text, the circumstances, the whatever, to a point you cannot say it’s Gombrowicz anymore. It’s something… I don’t know. I’m sorry, the guy’s around, but it’s rather—I shouldn’t say this—it’s very bad.

You talk about changing the text to the point where it’s not Gombrowicz anymore. How much was that a concern for you—this idea of how faithful to be, or how much license to take so that it can become its own thing?

I don’t know. I know that everything people say, the long monologues, the things Witold writes on his computer, this is in fact pure Gombrowicz, this is the text. But whether they go here or there or do this or that… this is an adaptation and a script has to be a script. Gombrowicz didn’t give a fuck for any kind of logic. For instance, he allows himself to write that, okay, two people go to the garden, there are two, and suddenly one of them disappears. The one who stays never wonders what happened to the other. You cannot write a script this way. People will say: “What did they do with the other guy? Did they cut it? He got erased?” So there are certain simple rules we cannot avoid in writing scripts. Even Mel Brooks respects…

The Aristotelian unities?

The grammar of cinema.

I like the phrase that you used with regard to Gombrowicz, which is a “savage provocation,” and I wonder if that to a certain extent could be applied to what you hoped to do with this movie, a sort of gauntlet-throwing?

In Gombrowicz’s case, it was an act of anger, defiance, and an attack on a very claustrophobic bourgeois society, first in Poland then in France, in his plays. Therefore, one can say it was political for him. In my case, not at all. This film could be shot in any country of Europe at any time, so it’s not an attack against something very precise. It’s an attack against stupidity and a lack of imagination, how a cosmos can be built with the smallest things, with the most unrelated human interactions. It’s a cosmos. It can be on the contrary, like a precise mechanism, but then I wouldn’t believe it because a cosmos who finally says… Yeah, this is a cosmos: here, this bottle, this thing, your reflection in the mirror, the mosquito that just bit me. I never saw him, he was so little, so small. It’s a cosmos. This was strongly appealing to me, by the end of my life, to see that it’s absurd but not in an absurd way.

That seems to be where a lot of the humor of the film comes from: trying to make, as you say, an order, trying to create some logic out of wholly unrelated and random objects.

It is a story of the human mind.

And you have a very, very funny postscript.

It’s the last sentence of the book. He says: “At dinner we had chicken with béchamel sauce.”