Locarno 2021: CINEMA IS BACK

This article appeared in the August 19 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

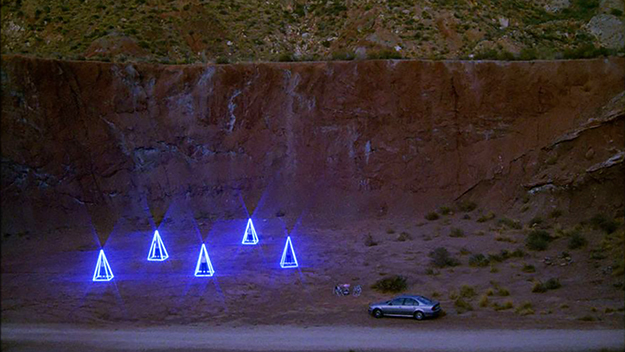

Espíritu Sagrado (Chema García Ibarra, 2021)

Around eight seconds into the inaugural press screening at the 74th Locarno Film Festival (the first to happen physically since 2019), irony struck. In the festival’s ident, a handsome leopard—an emblem which gives rise to such covetable merch that the Locarno lanyard is often squirrelled away and repurposed for use at less graphically blessed festivals—strolls across the screen. This year, the leopard was followed by a yellow screen announcing in bold black type: CINEMA IS BACK. That it then immediately cut to the Netflix logo was, not to overstate, sort of hilarious. Whatever you think about Netflix as cinema, it’s certainly not an entity that can by any stretch be described as having “gone away” during the pandemic.

However, that the film which then unfolded was lackluster wrong-man actioner Beckett, starring John David Washington, maybe stretched the joke too far. Festival openers are a notoriously poor bellwether for the rest of the selection, but if Beckett could be taken as an indicator of Locarno’s much-touted pivot toward genre under the new artistic directorship of Giona A. Nazzaro, its ho-hum quality hardly boded well. Especially given that, as much as every film festival is in flux right now, Locarno is even more so, contending not just with Covid-19 but also with its second change of artistic direction in three editions. And with the abrupt departure of previous head Lili Hinstin so seldom mentioned at the festival it might never have happened at all, Nazzaro’s push to make Locarno’s heavy-arthouse rep more genre-oriented became a major talking point.

It was a mission that made itself felt throughout the selection, in Competition titles like Edwin’s Golden Leopard–winning genre mash-up Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash and Abel Ferrara’s confoundingly, somehow dazzlingly murky Zeros and Ones, which can loosely be described as dystopian science fiction. Less successful was Cop Secret, a Reykjavík–set Hollywood-cop-movie pastiche directed by Hannes Þór Halldórsson, who also happens to be the Icelandic football team’s goalkeeper. Rumors that the film had been included as a thank you to its director for the home team’s 6-0 victory in a 2018 Switzerland-Iceland match remain scurrilously unsubstantiated.

The Piazza Grande section, which traditionally skews more mainstream anyway, was positively lousy with genre films. Of these, dumb-fun Korean disaster comedy Sinkhole and sprawling but derivative Jordanian gangster movie The Alleys are at least less likely to bother the local multiplex in the near future. But with Hollywood represented by the low-impact premieres of Beckett and uninspiring crime B-movie Ida Red—and by screenings of the simultaneously released sci-fi comedy Free Guy and the Aretha Franklin biopic Respect—it did feel like Locarno was rather struggling to make its new direction viable.

Still, despite mutinous murmurings from longtime attendees, it was quite possible to curate a less generic journey through the 200-plus movie selection, out of which compelling themes emerged. Skittering through all the sections I sampled was a highly topical investigation of faith and superstition, and the insidious ways in which they can be manipulated by the powerful to further oppress the marginalized. Holy Emy, the impressive debut from Greek director Araceli Lemos, certainly fit this bill with its uncanny yet realist drama about a young Filipina immigrant in Athens with mystical healing powers. So too did the absorbing Critics’ Week documentary A Thousand Fires, from director Saeed Taji Farouky, which patiently observes a family of artisan oil-drillers in Myanmar as they visit mystics, shrines, and sacred mud springs to barter with luck, karma, the Gods, whomever to secure the future of their eldest son. Religious dogmatism was background radiation in Francesco Montagner’s documentary Brotherhood, winner of the Filmmakers of the Present sidebar, in which three Bosnian farming brothers must fend for themselves when their father goes to prison for Islamic terrorist activities. And in Ferrara’s film, it is explicitly a Holy War, playing out on the streets of Rome, that Ethan Hawke’s soldier is caught up in.

But the exploitation of belief, superstition, and the gullibility of decent people looking—in all the wrong places—for order in a chaotic world came to the blistering fore in Espíritu Sagrado, by some distance the best film I saw in Locarno this year (though it only garnered a Special Mention from Eliza Hittman’s jury). Chema García Ibarra’s disconcertingly funny portrait of the UFOlogists, psychics, quacks, gurus, and other crackpots in a provincial Spanish town is similar in its deadpan-grotesque tone to Bruno Dumont’s Li’l Quinquin, right up until it gently detonates its audacious bombshell-downer of an ending.

Can we believe in a thing we cannot see, be it a higher alien plane, a guiding spirit whose favor can be bought and sold, or the healing powers of an immigrant? The Locarno 2021 selection—not one for the ages, but studded with striking titles here and there—understood not only that we can and do, but that therein lies half the madness, and a great deal of the misery, of the modern world. As uneven and uncertain as the festival’s restart might have been, in that observation, Locarno 74 felt vitally, if soberingly, current.

Jessica Kiang is a freelance film critic with regular bylines at Variety, The Playlist, The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and Sight & Sound.