Knowing Me, Knowing You: I Knew Her Well + Marguerite

In her new weekly column, Violet Lucca takes on the latest cultural debates in film and the world at large, weaving together criticism with a response to the issues of the day.

I Knew Her Well

Expecting your favorite famous person to share your beliefs has always struck me as a fool’s errand. Great artistry isn’t contingent on good politics, or vice versa. Any celebrity’s public persona is mediated and constructed by (most likely a team of) publicists, advisors, and agents, regardless of how casual and “real” it appears to be. While this seems like a painfully obvious point to make, it’s a fact that gets obscured by the false transparency that social media and interviews offer. The likes of Charlotte Rampling, Michael Caine, and Julie Delpy are still products of their upbringing and surroundings, as we are reminded when they say, with great confidence, something head-slappingly ignorant. (Do you know many septuagenarians who aren’t professors that are familiar with intersectionality?) It’s always worth bearing in mind the gulf between star text and human being.

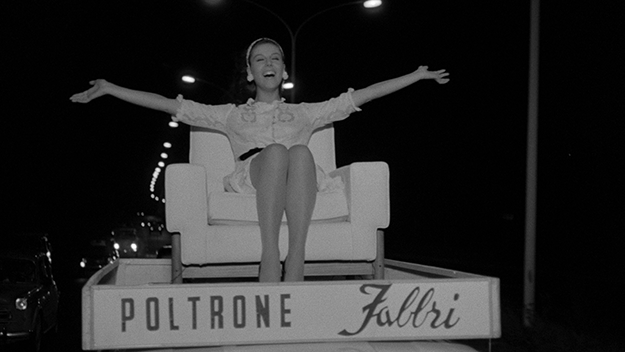

The process of fabricating a glowing persona can be glimpsed from another perspective in Antonio Pietrangeli’s superbly crafted I Knew Her Well, which this Friday gets a very welcome revival. In Pietrangeli’s 1965 picture, Adriana (Stefania Sandreli) —or “Adri Astin” as her lecherous and talentless talent agent rechristens her—is an aspiring and appealing actress in Rome, living an alternately bohemian and glamorous existence. Such incongruity is just an occupational hazard of the movie business: for every scene in which she sleepwalks through some crappy part-time job, there are about five more that show her partying while dressed to the nines. Through 19 episodic sequences, each generally entered in media res, we witness Adriana good-naturedly taking an aimless path toward stardom. Due to the film’s elliptical treatment of time and context, it’s unclear if she has been detoured from or is closing in on her goal. In a sequence where she goes on-location for a week to shoot a historical epic with chariots, it’s unclear whether she’s the lead or just an extra; instead of acting, we only see her rushing to a trailer to call potential beau Franco Nero back in Rome. (This sort of misdirection runs throughout all of her acting work, such as her first gig, where she wears a gown and pearls… for a commercial that only shows her calves in knee-high boots.)

What Adriana is thinking or feeling is also left ambiguous. She demonstrates a degree of agency: free and open with her sexuality, she won’t sleep with anybody to get ahead (she rebuffs an elderly actor’s invitation per un drink after a party because she finds it impolite), but she’s also not naïve enough to get sentimental about the guys she has a good time with (she laughs off a detective’s scorn for her not knowing the surname of an ex who stole a bracelet for her). But unlike, say, Diana Scott in Darling from the same year, she’s obviously not calculating enough to get ahead in the business, even if she weren’t surrounded by Day of the Locust-caliber industry types.

I Knew Her Well

Adriana’s approach to life and to her career is best summarized by a middle-aged author whom she’s seeing—and who, somewhat predictably, is pillaging her life for his next book. “She’s not curious about anything. Zero ambition,” the writer says of his novel’s protagonist. “Living day to day would require too much planning so she lives for the moment.” Mortified, Adriana asks: “Is that what I’m like? Some dimwit?” Without any condescension, he replies: “On the contrary. You might be the wisest of all.”

This isn’t the first time Adriana finds her identity being passively constructed by a man. In an earlier scene, she visits her agent’s septuagenarian assistant, a seasoned starlet-maker who’s “discovered” several actresses (all of whom Adriana needs a few moments to recall). and he narrates a hunted and pecked list of generically wholesome interests and hopes on a continuously jamming typewriter. (Appropriately, the list is typed directly onto a form for some nameless publication.) When he finishes, she asks: “Is he talking about me?” They’re quick to assure her it’s the best thing for her career.

What we are given of her laissez-faire life are just as oblique and abstract as the list this man creates—she goes to parties, some better than others; she sleeps with men, some better than others—which makes it impossible to judge or know her fully. Pietrangeli collapses his film with the star-making apparatus in other subtle ways: the film’s opening camera movements, which trace Sandreli’s curves while sunbathing, are repeated by a newsreel crew that interviews her while she’s lounging on a bed at a party. When she sees the finished product with her former coworkers at a movie theater, it’s been edited to make her look like a casting-couch aficionado. This humiliation no doubt influences the film’s sudden, shocking conclusion. (Being groped by a fresh pre-teen boy as she tries to give him a well-meaning slow dance lesson also doesn’t help.)

Marguerite

Would Adriana have had a better time if she’d had a little more control in manufacturing her own image? Another upcoming release, Xavier Giannoli’s Marguerite, presents that kind of control in a very different light. In post-WWI France, the titular Baroness Marguerite Dumont (Catherine Frot) fancies herself a world-class coloratura soprano even though she can’t hit or hold simple notes. Her husband, who married her for her money and is having an affair, humors her because it’s the path of least resistance. However, her fantasy takes on new dimensions when two Dadaists catch her performing at a concert for war orphans: one writes a glowing review of her singing, another books her to perform “La Marseillaise” at one of his inflammatory happenings.

The subsequent scandal distances Marguerite from her society friends and pushes her deeper into the realms of Paris’s avant-garde, who alternate between wanting to protect her feelings and getting more of her cash. Her new crew eventually help her stage a solo show at an opera house, an event that fully reveals how little her husband cares about her—the far more insidious prison of misconception that’s been ruining her life. As the story unfolded, I was naturally reminded of Donald Trump’s decision to buy his way into the race for president (and, in the instance of his debate boycott/veterans’ fundraiser, using money to avoid participating in the democratic process when he doesn’t feel like it). While his actual politics (or gestures towards faith) are a far cry from Marguerite’s benign love of music, it’s an intriguing comparative study in how unlimited finances coupled with large, fragile egos can result in something freakish.

Yet Marguerite is complicated by the presence of Marguerite’s butler, Madelbros (Denis Mpunga). Although he works overtime to maintain his employer’s stature, he’s also an amateur photographer who services his mistress’s delusion in the name of his art: photo shoots for which he dresses and poses her as the lead in famous operas. (Many of these snaps have more than a little erotic undercurrent, her skin bared and pleased smile upon her lips.) Madelbros’s still camera doesn’t support her fantasies of adulation and love, but instead mediates and reshapes them: visitors to the house frequently mistake his photos as proof of her illustrious career (until they hear her sing).

Marguerite

It is, for one thing, a fascinating reversal of photography’s role in Orientalizing non-whites (and creating narratives around the exotic), but Giannoli, who co-wrote the script, doesn’t diminish the insidiousness of Madelbros’s art project. The final shot of the film is of an unconscious Marguerite, who has fainted upon hearing a recording of her voice, being held by her husband—a scene again opportunistically staged by her butler. The grotesqueness of Mandelbros’s manipulation—made even more so by how quietly plays out—is arresting and odd. It’s a poetic reminder that being fit into the mold of performer is beset by danger on all sides.