↔ (Part Two)

Read and watch B. Kite’s original essays here.

I’d like to rack focus from process to thematic concerns for a bit, or at least start thinking about how they’re conjoined. Just as the “two-fisted Bresson” is a little misleading, so is the strictly process-oriented Bresson.

I think a lot of the initial “Bresson is [X]” stuff (austere, Jansenist, minimalist, and so on) was a way of coping with his utter strangeness within the context of film culture in the 60s and 70s. The current (but maybe close-to-exhausted?) “Bresson is not [X]” pronouncements strike me as something else again, namely a manifestation of the reflexive discomfort in certain pockets of Western intellectual culture with Christianity. Anything Christian is either condemned, nullified, or, in the case of artists for whom Christianity is less than wholly negative (in cinema: Bresson, Olmi, Pasolini, Rohmer, Ferrara, Tarkovsky), either denied, sidelined, or neutralized.

It seems to me that the reflexive branding of Christianity as only negative is actually an identity issue, and that the many horrors and idiocies perpetrated in the name of Roman Catholicism and fundamentalist protestantism are less the cause of this reaction than its perpetual justification. On these shores, with the Culture War in full swing, I think this is a late manifestation of countercultural anti-authoritarianism, albeit shrunken down to the sphere of the self (I wish there were a lot more of this spirit in practical politics and a little less of it in writing and blogging, but that’s a topic for another day). In film criticism, this has taken the form of some strange and even desperate attempts to re-frame Bresson in the contexts of eroticism, modernism, revolutionary politics, anarchism, atheism, and so on and on and on… anything but Christianity.

L’Argent

Of course, organized religion in France and in the U.S. are two extremely different matters, and Bresson’s relationship with Christianity was complex right from the start. His three most overtly Christian films—Les Anges du pêché, Diary of a Country Priest and The Trial of Joan of Arc—are not exactly The Bishop’s Wife or Miracle of Marcellino. In Bresson, as in Malick, Godard, Buñuel, Bergman, and Tarkovsky but even more powerfully, one feels the massive spiritual, philosophical, institutional, and aesthetic presence of Christianity, and (as in Dostoyevsky) its animating ideas of love, charity, and forgiveness endlessly complicated by humanity. It’s not that Bresson is promoting Christianity (I’m not sure that anyone really believes this to be the case, but one gets the feeling that all those persistent denials add up to a fear that he might be), but rather acknowledging its centrality and its enormity within the common life of the Western world – in other words, something so great that it can not simply be ignored or magically expunged.

It has been suggested that Bresson had become an atheist by the time he made The Devil, Probably and L’Argent. In fact, I think that his engagement with the question of faith ran so deep that he was the only artist to actually dramatize the slow and extremely fraught and painful “paradigm shift” described by the Italian Catholic philosopher Gianni Vattimo: “Nietzsche writes that God is dead because those who believe in him have killed him. In other words, the faithful, who have learned not to lie because it is God’s command, have discovered in the end that God himself is a superfluous lie . . . since God can no longer be upheld as an ultimate foundation, as the absolute metaphysical structure of the real, it is possible, once again, to believe in God.” Not the God “of metaphysics,” but the God “of the Book . . . who does not ‘exist’ as an objective reality outside of salvation’s announcement, is always handed over in historically changing forms offered, in the sacred scriptures and in the living tradition of the Church, to the continuing reinterpretation of the community of believers.” Vattimo’s description of his own renewal of faith by way of Nietzsche and Heidegger (“I believe that I believe”) points to a seismic transformation that arguably began close to a century ago and will probably take a couple more centuries to complete. The fallout is felt on a daily level in the increasingly violent and hysterical efforts to reverse course by the Vatican and the fundamentalist establishment. But one can also feel the effects of this shift in the painful confusion and disillusionment of people for whom lack of metaphysical certainty fuses with ecological, economic, and human horror to form a solid core of despair. If there’s a more illuminating film about modern distress than The Devil, Probably or L’Argent, I haven’t seen it.

The greater the artist, the bigger the world within which his/her characters and objects and events and transformations form and live and react. And the greater the freedom to pursue fleeting sensations, quickly alighting intuitions, shivers of desire in which one finds oneself suddenly magnetized by your beloved quarter turn landing on the beat of the ding, the clicking of glass shards cleaned with a wet sponge from a wooden floor (one really becomes delicately tuned to the rhythm of this leading to that in Bresson), lanterns suddenly appearing in the frame like signals to another enchanted level, or stops of musical color, or both at once.

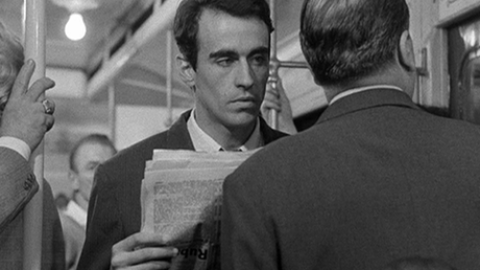

The Asphalt Jungle

In his piece on John Huston, Manny Farber writes about two “exquisitely cinematic” moments from The Asphalt Jungle: “. . . the safe-cracker, one hand already engaged, removing the cork from the nitro bottle with his teeth; the sharp, clean thrust of the chisel as it slices through the wooden strut.” (Actually, he got it wrong: it’s mortar.)

Cinematic, or, as Chandler reminds us, sensual: “My theory was that the readers just thought they cared about nothing but the action. The things they remembered, that haunted them, [were] not, for example, that a man got killed but that in the moment of his death he was trying to pick a paper clip up off the polished surface of a desk and it kept slipping away from him.” Other examples from movies: the bullet hitting the hanging melon in Day of the Jackal; Gene Kelly gliding around the corner on roller skates in It’s Always Fair Weather; your Damsel in Distress example, and so many other moments with Astaire (like his backward turning leap up to the table in the “I Love Luisa” number in The Band Wagon).

The Day of the Jackal

It’s Always Fair Weather

The Band Wagon

In each case, it’s a matter of satisfaction, of sensual contact, of expectations met, of pure correlation, life and cinema commingling in a bright, sensual flash. Which, I think, is where the road opens to audiences loving filmmakers in what they love and the way in which they love things and people.

B. Kite’s original video essay