Kaiju Shakedown: Two-Part Movies

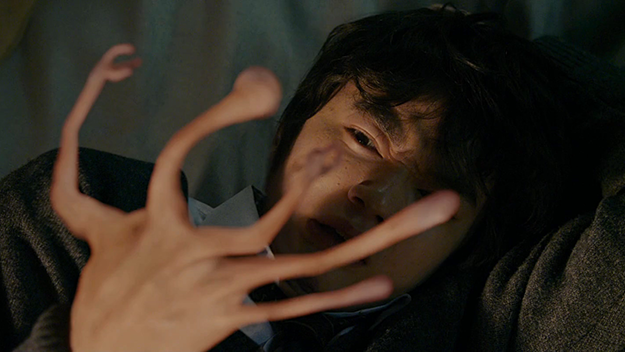

Solomon’s Perjury Part 1: Suspicion

Forget splitting the last of the Harry Potter series into two parts, or the four-part Hunger Games trilogy. If you look at what’s coming out of Japan recently you’d think there’s no longer a story that can be contained in a single movie: Gantz (January 2011) and Gantz: Perfect Answer (April 2011); Parasyte: Part 1 (November 2014) and Parasyte: Part 2 (April 2015); Solomon’s Perjury Part 1: Suspicion (March 2015) and Solomon’s Perjury Part 2: Judgement (April 2015); Attack on Titan (August 2015) and Attack on Titan: End of the World (September 2015). And it’s not just Japan. This year India’s Baahubali: The Beginning rapidly became India’s top-grossing movie of all time, and Baahubali: The Conclusion, shot simultaneously with the first half, will be released in 2016.

These aren’t sequels—they’re single movies that have been split over two films and released in rapid succession. Even the stand-alone sequels were shot at the same time with their predecessors, to be released less than a year later. From a production point of view, it makes sense to split things up if you have a big property: two movies will always make more than one at the box office; you can do all your effects work at once; and there’s only one contract with the actors. The biggest challenge is closing that window between the first film and the second.

Akihiro Yamauchi, producer of the two-part Attack on Titan said in an interview with Yomiuri Shimbun: “It’s hard to keep moviegoers interested in one work as new films are released one after another. Their interest . . . is at the highest level immediately after seeing the first part.” Producers have been doing everything they can to reduce that gap, and this summer’s Attack on Titan Part 2: The End of the World will appear just six weeks after Part 1.

Parasyte: Part 1

People have traced this trend back to the Lord of the Rings series (01-03) which was originally slated to be a two-part project, or to Kill Bill (03-04), which was broken up into two films during editing. Others have pointed to Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers (73) which was split into two movies during production under disputed circumstances. But the practice used to be much more prevalent, with releases coming out mere days apart, and it had its beginnings in Japan.

The first two-part feature film I can find was Akira Kurosawa’s 265-minute adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (51). Originally a two-part movie, Shochiku hacked it to shreds against Kurosawa’s wishes after a poorly received early screening. In 1958, Shochiku’s bullheaded Masaki Kobayashi, bought the rights to Junpei Gomikawa’s six-part memoir, The Human Condition, and insisted on shooting it as three films which Shochiku, reluctantly, agreed to release intact between 1959 and 1961. The saga established Kobayashi’s reputation and won awards all over the world.

While this was going on, Hong Kong’s Cathay (aka MP&GI) and their rival, Shaw Brothers, were taking note. Shaw, especially, made no bones about the fact that they were heavily influenced by Japanese movies and trends, sending its directors to serve internships at Japanese studios, and hiring numerous Japanese cinematographers to serve as in-house DPs. Because of their intense competition, Cathay would often announce a project only for Shaw to announce a similar project later with an earlier release date. That’s exactly what happened in 1960 when Cathay announced Bitter Lotus, a two-part contemporary love story. Within days, Shaw had announced their own contemporary love story, Foolish Heart (aka This Foolish Heart, aka Love Knot), and they beat Cathay to the box office by almost six weeks, stealing their thunder.

Sun, Moon, and Star

Cathay took it to the next level with Sun, Moon, and Star (61), a massive two-parter set during the Sino-Japanese War and starring their three biggest divas (You Min, Grace Chang, Julie Yeh Feng). Based on a novel by Xu Su (which had started as an essay before metastasizing) it took one-and-a-half years to shoot. The movie was such a box office success that in 1962 Xu Su published a revised edition of his book that incorporated numerous changes from the film. Both parts hit theaters in December, about three weeks apart, and Cathay pressed their advantage with Crossed Swords (62) whose two parts were released about one week apart that August, and Story of Three Loves (64) which came out in two sections over a two-week period around Valentine’s Day (and Chinese New Year) of 1964.

Shaw wasn’t having it, and in 1964 they began shooting their own massive two-parter The Blue and the Black (66), also based on a novel set during the Sino-Japanese war. In their attempt to blow Cathay out of the water they cast Linda Lin Dai, probably the biggest star of the day, as their lead, and it was directed by Doe Ching whom their publicity department dubbed “China’s Hitchcock.” Towards the end of filming, Lin Dai killed herself (she was 29) and the movie stopped production. Two years later it was released using Elsie Tu as a stand-in for Lin Dai’s unfilmed scenes, and it minted money at the box office. In, Seoul, at the influential Asian Film Festival, it took home Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Colour Photography, and an additional special award.

Running time has always been a battleground in Hong Kong, with distributors sometimes editing down a movie to squeeze in more shows in a day (as happened to Tsui Hark with 1992’s Dragon Inn), and production pace is often so breathless that it’s difficult to tell what’s a two-parter and what’s a sequel, as in the case of Young and Dangerous (96)—a surprise hit that had a sequel written, shot, edited, and released within eight weeks of the first movie’s opening night. In a sense, every Hong Kong movie was a two-parter in the Nineties since distributors split them onto two VHS tapes (and, later, two laserdiscs) for the home video market so they could charge retailers twice for one movie.

Chinese Odyssey Part I – Pandora’s Box

But there weren’t any more official Hong Kong two-parters until Wong Jing, master of sequels and penny-pinching, adapted the hugely popular Duke of Mount Deer novel starring comedian Stephen Chow, shooting Royal Tramp (92) and Royal Tramp II (92) simultaneously. Then came Chinese Odyssey (95), Jeff Lau’s massive, two-part adaptation of the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, starring Stephen Chow as the Monkey King. It was Lau’s response to his collaborator, Wong Kar Wai’s wuxia film Ashes of Time, shot on many of the same sets and with the same costumes. While Lau prefers the 135-minute cut of his film, the distributor split it into two 90-minute movies, Chinese Odyssey Part I – Pandora’s Box and A Chinese Odyssey Part II – Cinderella, released about two weeks apart over Chinese New Year. Considered modern day classics, the two movies freed Chow from the grind of making low-budget comedies, but no one followed in their footsteps.

The common trend for two-part movies to this point was that they were based on huge properties that had a built-in audience, mostly famous novels. By 2006, only two kinds of property had that cachet: manga and national myths. The first of the new wave of two-parters was Death Note (06), based on a 12-volume manga that was ranked as one of the 10 greatest of all time, with 30 million copies in print. NTV and director Shusuke Kaneko knew they had to stay faithful to their source to please fans, and that meant… two parts. The movies were an enormous success, fueled by the core audience who loved the faithfulness of the adaptation.

After that, the floodgates opened. In 2008, another popular manga, 20th Century Boys, about a global conspiracy, was divided into three parts that were shot simultaneously and then released one at a time every six months. Then came another manga adaptation, Gantz and Gantz: Perfect Answer, and then swordsman manga Rurouni Kenshin (12) turned out to be so popular that its sequel was split into two parts, shot simultaneously and released one month apart in 2014. An adaptation of the manga Parasyte (14) followed, and now the film adaptation of the manga Attack on Titan has been released in August, with part two lined up for September. The only film that bucked this trend was Solomon’s Perjury, a crime drama based on a novel by Miyuki Miyabe that was serialized over the course of nine years rather than on a manga. Solomon’s Perjury Part 1: Suspicion was still running in theaters when, four weeks later, Solomon’s Perjury Part 2: Judgement came out.

Seediq Bale Part 2

Outside of Japan, the only properties that receive this two-part treatment are national myths, like Thailand’s two-part King Naresuan (07), which tells the tale of the founding of Thailand and was released in January and February of 2007 (a third part appeared four years later). John Woo’s Red Cliff (09) a gigantic movie based on Story of the Three Kingdoms, one of the foundational texts of Chinese literature, had both of its halves shot simultaneously. In Taiwan, blockbuster director Wei Te-Sheng marshalled all of his country’s resources to film Seediq Bale in two parts, both released in 2011. Wei’s epic story of the indigenous Seediq people rising up against the occupying Japanese army cut through Taiwan’s complicated origins to create a national myth out of a hitherto minor historical incident.

But are these movies any good? Death Note was famous for its plot twists which required two movies to unpack, and Red Cliff and Seediq Bale both gain epic grandeur from their epic running times, but a movie like Solomon’s Perjury starts strong in Part 1, then degenerates into narrative wheel-spinning, long tear-stained speeches, and fabricated suspense in Part 2 as it drags out what should have been the 30-minute climax of Part 1 to 146 minutes. There are also cases where the first movie was such a flop that Part 2 never got released. John Woo tried to recapture the magic of Red Cliff with The Crossing (14), a star-studded, 3-D melodrama about the real-life sinking of the Taiping, a ship carrying over 1,000 refugees fleeing China’s Communist Revolution in 1949. Part 1 was such a huge bomb that Woo’s longtime collaborator, Tsui Hark, was brought in to edit Part 2, to no avail. Both halves sank at the box office without a trace.

Even more humiliating was Donnie Yen’s Iceman 3D (14) a remake of classic action film The Iceman Cometh (89). The budget for this tale of a frozen Ming Dynasty cop (Yen) who is thawed out in 2014 doubled during a shoot plagued with problems. Presented with a first cut of over three hours, the producers decided to hack it in two rather than dump their expensive footage, but on its release in April, 2014 the movie died at the box office, with Yen’s martial arts obscured by shoddy CGI and slathered with childish gags (pee jokes and exploding toilets abound). A final title screen promises that Iceman 2 would be arriving in December, but the first one was such a flop that no one ever bothered to complete the follow-up and it remains unseen over a year later.

LINKS! LINKS! LINKS!

Now that the Toronto Film Festival has announced its lineup, here’s everything Asian that’s making its bow, ranked by me in order of interest. (Trailers for the movies are on the linked festival pages, but sometimes the trailer is just too good not to get a special mention.)

Collective Invention (Korea, dir. Kwon Oh-Kwang)

Awesome concept + unknown director = maximum potential. An unemployed chump volunteers to test an experimental drug with one nasty side-effect: it turns him into a fish. Then he gets famous. At a time when film festivals seem to be going out of their way to play it safe, the trailer promises gonzo fun.

Hong Kong Trilogy: Preschooled Preoccupied Preposterous (Hong Kong, dir. Christopher Doyle)

One of the world’s greatest cinematographers directs a three-part movie about three different generations in Hong Kong. The first part was commissioned by the HKIFF and parts two and three were Kickstarted. Part two was shot during the Umbrella Revolution last year and promises to be the first feature film shot in and about Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. The trailer makes it look unmissable.

Honor Thy Father (Philippines, dir. Erik Matti)

After the scathing On the Job about Filipino hitmen, Matti returns with a crime drama about a pair of con artists and their victims. The movie was excluded from the Metro Manila Film Festival for unknown reasons, and star John Lloyd Cruz was warned by his management not to participate in the movie because the role required him to shave his head and they were worried about his shampoo sponsorship.

Office (Hong Kong/China, dir. Johnnie To)

There’s not much you need to know about this movie except it’s a musical about office life, starring Chow Yun-fat and Sylvia Chang (see Murmur of the Hearts). Based on even those limited specs, it’s one of Toronto’s must-see movies.

Murmur of the Hearts (Taiwan/Hong Kong, dir. Sylvia Chang)

It’s the year of Sylvia Chang at TIFF: she’s in the new Jia Zhang-ke movie, she appears in Office (which is based on a musical she wrote), and she turns in another one of her exquisitely directed, deeply emotional dramas with Murmur of the Hearts. After nine months of editing, she delivered a movie that’s being called “her most accomplished directing job to date, a tour-de-force of flashbacks and flash-forwards, interwoven characters, dreams, fantasy and reality.”

A Copy of My Mind (Indonesia/South Korea, dir. Joko Anwar)

After winning a development grant from Korea’s CJ entertainment, A Copy of My Mind became the only Southeast Asian film to appear at the Venice Film Festival. Now, this romantic drama about a beauty salon worker and a pirate DVD fan who wind up in possession of evidence in a political scandal is playing TIFF. What makes it worthwhile is that it’s from Joko Anwar, who might be one of the most deranged and psychologically intense directors, practically unique in the field of Asian cinema today.

Mr. Six (China, dir. Guan Hu)

Set for a North American release in December from China Lion, after closing the Venice Film Festival in September, this movie comes from the director of the under-seen and acclaimed WWII comedy/drama, Cow (09). It stars super-director Feng Xiaogang (Assembly, If You Are the One) as an elderly criminal who’s pulled back into the game to seek revenge after his son runs afoul of some gangsters.

Veteran (Korea, dir. Ryoo Seung-Wan)

A straightforward cop film from Ryoo Seung-Wan is still worth watching and while this one has a decent story at its heart (about a cop taking down the corrupt son of a wealthy family) ultimately what we’re here for is the action. And according to the trailer there’s plenty of that on display. Ryoo’s last couple of movies have seen him moving in a more mainstream direction and that’s not entirely a bad thing.

A Tale of Three Cities (China, dir. Mabel Cheung)

This story about two widows who meet in China and abandon their children to flee the war has been ambitiously compared by its director (New Waver Mabel Cheung) to Gone with the Wind, and it stars popular actors Lau Ching-wan and Mainland actress Tang Wei. But what gives it some must-see value isn’t just the slick visuals, but the rumor that it’s based on the actual story of Jackie Chan’s parents (and it’s produced by Huayi, Chan’s current home studio).

Yakuza Apocalypse (Japan, dir. Takashi Miike)

Straight outta Cannes and already picked up for a North American release from Samuel Goldwyn, Takashi Miike’s vampire gangster movie was pretty much a shoo-in for Toronto’s Midnight Madness unless it was utter crap. And—boing!—here it is. Looking very un-crap-like indeed!

SPL 2 – A Time For Consequences (Hong Kong, dir. Soi Cheang)

The reviews haven’t been great for this cash-in on the by-now-10-years-old action movie SPL. But with Wu Jing and Tony Jaa on hand, Soi Cheang (Motorway) in the director’s chair, and action choreographed by Nicky Li (Project A II, Shaolin) you know you’re in for some fine punching and kicking at the very least.

In the Room (Hong Kong/Singapore, dir. Eric Khoo)

Eric Khoo’s “erotic drama” is produced by Nansun Shi and stars Josie Ho and Choi Woo-Shik as two members of several different couples that cross paths and have romantic rendezvous in one room in a brothel over several decades, starting in 1942 and ending in the present. Being an Eric Khoo film it’s bound to be disaffected, abstract, depressing, and full of tears, which are exactly the wrong bodily fluid you want to find in your erotic drama.

The Assassin (Taiwan, dir. Hou Hsiao-hsien)

Almost 50,000 years in the making, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwan’s master of contemplative filmmaking, finally delivers his first action movie—a wuxia starring superstar Shu Qi that arrives floating on a cloud of praise from its debut at Cannes.

Our Little Sister (Japan, dir. Hirokazu Kore-eda)

Already earning big accolades, Kore-eda’s family drama about the bonds between three sisters (and one half-sister) is, again, a movie it would be more surprising not to see at TIFF. But there is something so astounding about the fact that Kore-eda turns out assured, well-made movies on such a regular basis that it’s become easy to take him for granted.

Beeba Boys (Canada, dir. Deepa Mehta)

Although it’s a Canadian film, Deepa Mehta’s movie about Indian gangs in Canada is going to be too interesting to leave out. Mehta is a director with serious chops, as the smash-hit success of her Water proved. And here she’s got some genre-friendly material to sink her teeth into.

Guilty (India, dir. Meghna Gulzar)

Speaking of true crime, here’s a classic whodunit about a real-life murder in 2008. Starring the great Irrfan Khan, it’s an account of the Talwar Case which gripped India after 14-year-old Aarushi Talwar and her family’s domestic helper were found murdered. The parents were convicted of the crime, but this film supposedly seeks to exonerate them and rumor has it that they gave their own account of what happened to the director and the screenwriter worked closely with Aarushi’s aunt, who has been lobbying for years to free the Talwars.

The Whispering Star (Japan, dir. Sion Sono)

Originally one section of a three-part multimedia art installation, Sono’s new movie is an experimental science fiction film shot in the still-radioactive Fukushima region and starring Sono’s wife, actress Megumi Kagurazaka, as a robot deliverywoman.

Paths of the Soul (China, dir. Zhang Yang)

Shooting over the course of a year, Zhang Yang (Shower, Getting Home) delivers a docudrama about 11 Tibetans who make a 2,000 km religious pilgrimage on foot. “We shot this film at 4,000 meters altitude and above,” Zhang says in the press materials. “We were eating and sleeping on the road. We worked literally on the road. We had to live within extreme conditions, and these for us were more complicated than actually doing the film. Because this became our lives.” You gotta admire his commitment, and Zhang has always been good about staying on the right side of the line dividing entertaining drama from art-house twaddle.

Angry Indian Goddesses (India, dir. Pan Nalin)

Paris-based art-house director Pan Nalin makes his Hindi film industry debut with this female buddy movie starring a roster of mid- to high-profile actresses.

Invisible (Imbisibol) (Philippines/Japan, dir. Lawrence Fajardo)

Veteran director Fajardo turns in one of only two Filipino movies in this year’s TIFF, this one about the plight of undocumented Filipino workers in Japan (a topic also broached in 2013’s Blue Bustamante, only in that movie the undocumented Filipino workers in Japan were superheroes).

Cemetery of Splendour (Thailand, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

The latest contemplative movie from Thailand’s biggest art-house director, and it would have been a bombshell if it wasn’t being shown at TIFF.

Right Now, Wrong Then (Korea, dir. Hong Sang-Soo)

Korea’s Hong seems to be a director who exists largely on the film festival circuit and at the whims of a gallery of international festival programmers. And here’s his latest movie.

Journey to the Shore (Japan/France, dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Japan’s once-great horror auteur walked away from ghost films with 2008’s Tokyo Sonata but now he’s back, turning in a movie about a widow reunited with the ghost of her dead husband in a film that critics are calling “competent” and “delicate.”

Parched (India, dir. Leena Yadav)

Four Indian women find themselves and throw off the yoke of tradition in this “inspirational drama.”

Mountains May Depart (China, Jia Zhang-ke)

Art-house superstar Jia is a super-nice guy and film festival programmers love his movies because they see something in them, but I can’t get excited about a movie whose reviews are collections of adjectives like “somber,” “melancholic,” and “luminous,” which is a word that really should be reserved only for lightbulbs.

A Young Patriot (China/USA/France, dir. Du Haibin)

This giant documentary about “the breakdown of the so-called Chinese Dream” was shot over the course of five years in China and won Jury Prize for Best Documentary at the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Afternoon (Taiwan, dir. Tsai Ming-liang)

Director Tsai used to be one of Taiwan’s great art-house directors before turning his attention to fest fare, as with his recent movies about a Buddhist monk walking. Now he retreats even further into self-regard with this filmed encounter between himself and Lee Kang-sheng, the lead actor in almost all of his movies.