Kaiju Shakedown: Shunji Iwai

All About Lily Chou-Chou

Let Me Take You Down by Jack Jones is a 1992 true crime book about Mark David Chapman. Chapters two, three, and four are a moment-by-moment account of the 48 hours Chapman spent in New York City before he walked up to John Lennon on December 8, 1980 and shot him five times in the back. Recounting every move Chapman makes, from sitting in the wrong section of a restaurant, to a trip to a record store, to banal chitchat with other fans, it’s like a Haruki Murakami story where every single mundane detail is weighted with import because we know they’re all building toward something big.

Chapman has said more than once that he might not have shot John Lennon if only a photographer had stayed at the door of Lennon’s apartment building a little longer, or if only another fan had agreed to go out to dinner with him that night. Just one small detail changes, and everything would have been different. The world-changing importance of the tiny detail, a sense of branching paths leading to parallel universes, an acknowledgement of the emotional value of pop culture totem like albums, songs, and musicians—all this captured the attention of an up-and-coming Japanese television director named Shunji Iwai and intermingled with his creative DNA.

Starting out in television, Iwai directed 12 made-for-TV movies like Fireworks, Shall We See It From the Side or the Bottom? (93) that combined these concerns into incendiary devices that left scorch marks on viewer’s hearts. In Fireworks a bunch of schoolboys set off to settle a debate: are fireworks flat or are they round? The only way to decide is to view them from the side, and then the bottom. Time forks as Iwai shoots a swimming competition twice: each time a different boy wins, and Iwai follows both victors down parallel timelines. A schoolgirl runs away from home. Boys scream the names of the girls they love into the nighttime sky, masked by the sound of fireworks. “Sailor Moon!” shouts one. It’s impossible to sum up why this 50-minute film is so moving. Think of it like fireworks. No matter what you say, words don’t convey the feeling of sitting on a dark hillside and watching them briefly, brilliantly light up the sky.

Love Letter

In Iwai’s first feature, Love Letter (95), pop star Miho Nakayama plays a recently widowed woman who pours out her grief in a letter sent to her dead husband’s hometown. To her surprise, she gets a reply. Shot in snowy Hokkaido, critics wrote it off as flashy, MTV-esque packaging for a pop idol. It was released in just five theaters. At just one of them, it played for 14 sold-out, standing-room-only weeks. It won eight major film awards (including the Audience Award at the Toronto Film Festival) and became the first Japanese movie to play South Korean theaters since World War II (it was a hit there, too).

Next was Swallowtail Butterfly (96), a movie that occupies pretty much the same cultural territory in Japan that Pulp Fiction occupies in America. A near-future sci-fi film shot with handheld cameras and edited to a twitchy rhythm, Swallowtail posits an alternate history in which an economically flush Japan has attracted millions of immigrants, who live in the YenTown ghetto and work on the margins, always on the hustle, constantly trying to score that yen. Pop star Chara plays, well, a pop star who achieves fame when her YenTown comrades co-opt a Yakuza cash scam and become rich enough to open a nightclub and release albums. Fueled by Takeshi Kobayashi’s exuberantly moody J-pop soundtrack, shedding ideas at the speed of light, violent, sexy, propulsive, and young, it’s smart about identity, ethnicity, and the way money makes families, then breaks them.

Despite their wildly different subject matter, both movies are distinctly Iwai’s. Love Letter saw the beginning of his collaboration with cinematographer Noboru Shinoda, whose deceptively loose camerawork focuses first and foremost on faces. It also saw the beginning of a pattern where critics dismissed Iwai’s movies as style over substance. Mika Ko is just a more intellectual stand-in for other critics when she writes that the hectic racial diversity of Swallowtail is “cosmetic” and “The plot functions as nothing more than a device for packaging . . . MTV-like images of ‘others’ and ‘other cultures,’ along with funky pop music . . . as objects of consumption.”

April Story

For Iwai, style and substance are one. Cinema is not a novel to be analyzed and dissected in sterile academic journals, but a living art form that resists summary. It’s an effect, an emotion, or a mood, as much as it’s a plot, a soundtrack, or characters. The sexy, attractive, envy-inducing members of the YenTown band are a living rebuttal to the reduction of immigrants to the evil other: how can these seductive, fuckable, party-starting groovelings be evil or inferior?

Iwai’s minimalist, 64-minute-long April Story (98), which Derek Elley compared to a haiku, is handcrafted to the extent that Iwai designed the tickets and carted 35mm prints to theaters. On the surface, an hour-long movie about a young woman moving to a new town to start university is pretty thin. On the other hand, if it’s so thin, why do you finish the film feeling like someone’s injected helium into your soul? Sometimes happy is harder than sad, and April Story manages to capture the unconquerable optimism of youth on celluloid, ready and waiting to be tasted any time you need it. That’s no small feat.

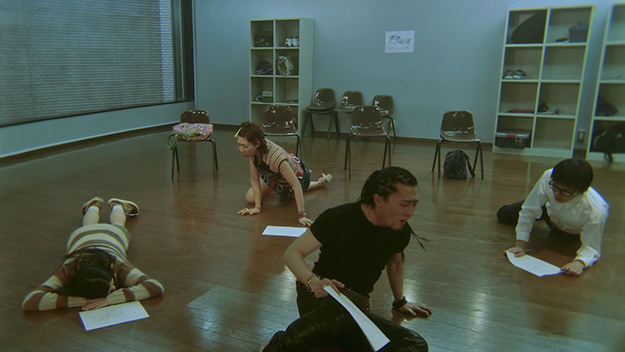

According to Iwai, Let Me Take You Down led both to April Story (which he views as an alternate-universe version of the story) and All About Lily Chou-Chou (01), a towering, shattering adolescence epic. Inspired by a Faye Wong concert, an early script that was brutally dissected by his fans, and a chat room that Iwai started about a fictitious pop star named Lily Chou-Chou, it’s a two-and-a-half-hour monster about kids in high school and their relationship with their favorite pop star (who never appears on screen). With long scenes of kids listening to Lily Chou-Chou on their headphones (Takeshi Kobayashi again provided music), Lily Chou-Chou sounds hermetically sealed from adult access by its relentless focus on youth, but it will break your heart no matter what your age.

Hana & Alice

Friends become enemies, enemies become friends, the class slut becomes the class saint, and the class saint gets gang raped. She refuses to report her attackers, and instead shows up to school with her head shaved, a sight so disconcerting that the teachers force her to wear a wig they have bought. Shimmering with the music of Debussy, peppered with machine-gun blasts of bulletin board messages (many written by real-life fans) from the Lily Chou-Chou chat rooms, the movie hits you like a hurricane.

Iwai’s loyal friendships with his casts and crew are well-known, and when a Kit Kat ad morphed into Hana & Alice (04), the tale of two BFF schoolgirls, no one was surprised that it was as sunny as Lily Chou-Chou was dark. One girl is a Type-A nerd and the other is a shambolic goof, and the movie is about the little things that loom large in high school. But unlike Lily Chou-Chou, here Iwai views them from an adult perspective, seeing the humor and the heartbreak simultaneously.

Iwai’s movies always spill outside the frame. “If I focus solely on the film, I almost feel like a child doing a report for school,” he said in a 2001 interview, and Love Letter became a novel and a manga, both written by Iwai. Chara’s YenTown Band from Swallowtail Butterfly wound up going on tour. Lily Chou-Chou chat rooms still exist, and Iwai occasionally adds to the original online novel. The cast of All About Lily Chou-Chou were mostly first-time actors recruited for the movie, and the set became an alternate high school, leaving the kids devastated on the last day of shooting. And, when Iwai’s cinematographer, Noboru Shinoda, died after shooting Hana & Alice, Iwai stopped making feature films in Japan.

Vampire

He made some shorts, he wrote and produced, he directed a poorly regarded horror movie in America called Vampire, as well as an animated prequel to Hana & Alice, and that was it. He’s got a new movie coming (Rip Van Winkle’s Bride), but without his friend the question is: will his heart be in it? Because Iwai is all about heart.

That’s why it’s easy to dismiss him as a lightweight. The grim old men of cinema consider heart less important than head. What fascinates Iwai are high school, friendships, fandom, pop music, women, and teenagers—not the kinds of thing “real” filmmakers are supposed to value. But Iwai digs into this devalued territory and finds moments of pure transcendence. A teenage call girl learns how to fly a kite. A shy high school student brings a dehumanizing modeling audition to a halt with a display of classical ballet. A college student goes fly-fishing. It snows in Hokkaido. As John Lennon said, “Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.”

LINKS! LINKS! LINKS!

All’s Well, Ends Well

… Happy Year of the Monkey! Chinese New Year is in full effect and that means it’s time for movies! In a blast from the past, the ur-Hong Kong Chinese New Year movie All’s Well, Ends Well (92) is being re-released in Hong Kong theaters with added footage that’s never been seen before in Hong Kong (and, reportedly, in cinemas that have vibrating seats).

… That doesn’t mean that there are no contemporary Chinese New Year movies duking it out at the box office. Stephen Chow’s Mermaid (he directs, but doesn’t appear) not only beat Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 3 at the box office, but grossed $42 million on its opening day in China—a record for the Mainland. This helped fuel an overall Chinese New Year weekend of $101 million, a 78 percent increase over last year’s New Year weekend.

… It doesn’t hurt that Chow’s latest is getting rave reviews and isn’t the Splash knock-off it first appeared to be. Singapore’s Insing.com says: “It is advisable that you clear your bladder before entering the cinema hall for The Mermaid.” Screen Daily enthuses about the film’s “powerful ecological message” but doesn’t have any useful bathroom advice. Maggie Lee at Variety says it’s “Easily the most delightful comic fantasy in Chinese-language cinema since his own Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons” and goes on to gush that “it’s increasingly rare to find a mainland Chinese blockbuster in which one is so swept up by the rich storyline and the charismatic cast that the technical aspects don’t even seem to matter.”

Angel of Bar 21

… If you’re looking for Thai movies, you want to be in France. The Festival International des Cinemas d’Asie is hosting a sidebar called “Forgotten Masters of Thai Cinema” that features restorations of rarely seen Thai classics. Bastian Meiresonne (remember him?) programmed this astonishing lineup of 12 films which includes Angel of Bar 21 (78), based on Sartre’s The Respectful Prostitute, set in a nightclub, and “influenced by Bob Fosse.” There’s also A Town in Fog (78) which is a slasher set in a country inn based on another foreign play (this time by Camus). Taxi Driver crossed with The Bicycle Thief is the description for Citizen I (77), another wildly popular Thai movie that was previously believed to be lost.

… Wisekwai has weighed in with his Top Ten Movies for 2015 list and it’s an essential guide to what’s worthwhile from Thailand last year. He’s got a lot to say about movies I haven’t even heard of, like The Black Death, a Thai zombie film shot on the same sets, and with the same costumes, as the epic King Naresuan. He also has good stuff to say about Korean-American director Josh Kim’s How to Win at Checkers Every Time, Wisit Sasanatieng’s Senior, and seven more.

… Finally, there’s more to Thailand than movies. If you want to see soap opera celebrities rumbling, the Land of Smiles is where you want to be. Enraged that her lover had left her for another woman, actress Napapa “Pat” Thantrakul (who is a fun person and loves dancing, according to her online bio) had her niece lure the Other Woman into an ambush. As soon as the rival came through the door, Pat’s friends and relatives attacked her, although they say that their victim arrived with her own posse, ready to rumble. This is why celebrities get paid big salaries: to keep us entertained.